Graham Reid | | 19 min read

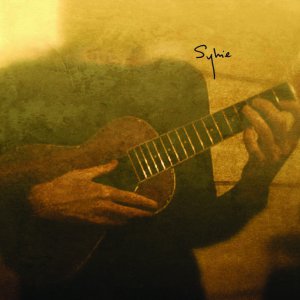

Sylvie Simmons: My Lips Still Taste of You

When Sylvie Simmons speaks it is in a quiet, bemused and droll English accent, full of whimsical asides. You'd be forgiven if you thought she was a slightly mischievous author of children's books.

But Simmons is one of the great music writers of our time who grew up “Beatle-damaged” in London of the Sixties, moved to America in the late Seventies where she wrote on metal bands, has been a longtime contributor to music magazines with insightful profiles of artists (in everything from Kerrang to Rolling Stone), and started the Americana column in Britain's Mojo magazine about 20 years ago

She has written music biographies – Motley Crue “to pay the rent”, Neil Young, Serge Gainsbourg among them – and she is working on another set of short stories based on music.

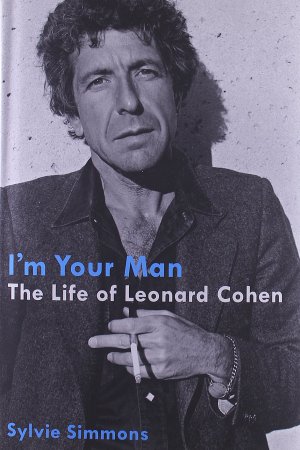

She has won awards for her liner note essays, spent a week with Johnny Cash in the last weeks of a his life and is perhaps best known for her recent and widely acclaimed biography of Leonard Cohen, I'm Your Man.

And now, in her early 60s, she has released her debut album (with Howe Gelb), a suitably quiet and reserved collection where she plays ukulele and which comes under the modest title Sylvie.

In 2013 she was in New Zealand and has fond memories of her book tour during which she played Cohen songs on ukulele, sometimes with local guests.

“I had the time of my life in New Zealand,” she says from bitterly cold New York, “and they treated me like an absolute queen. In Christchurch they found a very handsome man Adam McGrath to play with me, and Don McGlashan and I did a show together where we sang each others songs and some Leonard Cohen songs. What more could you want?”

So with an album out and the Cohen book behind her it seems we should start with her current project.

Sylvie, I can avoid talking to you

about the Leonard Cohen book because I imagine you are largely talked

out on it, so I can just address the album and maybe more general

questions about music journalism.

Sylvie, I can avoid talking to you

about the Leonard Cohen book because I imagine you are largely talked

out on it, so I can just address the album and maybe more general

questions about music journalism.

Whatever you would like to ask I am fine with, and I'm quite happy talking about the Leonard Cohen book in the sense that if it weren't for doing that I probably wouldn't have done an album at the end of it. So there's no subject off the record.

Then let's talk about that then, what drew you to ukulele . . . because the instrument has taken off globally, and certainly in this country.

It was just one those strange and mysterious things. I'd moved to San Francisco from London where I'm originally from on what was going to be a short adventure but turned out to be more adventurous than I thought.

So I'd left all my stuff in storage in England including my instruments that I play – guitar and piano and other things. I was without any instruments and somebody came into my life and gave me a ukulele, and suddenly I was obsessed with thing. Sometimes when people have new babies or puppies something they just become puppy or baby bores.

I became a ukulele bore and couldn't put the damn thing down. And really the instrument and I got along so well it was like I added it as a companion. I didn't take it everywhere though.

In America you can get a service animal you can take to a restaurant on the grounds that you'll be too nervous if you can't take your pet turtle with you, but I didn't take my ukulele into public places like that.

But when I was on the road interviewing people for the Leonard Cohen book, which was a long process, I had the ukulele there. I just stuck around. So when I did the book tour I took the ukulele with me and eventually it became part of the promotion. I was the human jukebox singing some of Leonard Cohen's songs with it.

So the ukulele came into my life, a guy had left it overnight and by the morning I was playing it, in several degrees of badness. But somehow over time it because this sweet little thing that was an outlet.

What was the appeal of the instrument itself? The elegant simplicity?

I wouldn't say elegant simplicity, it's partly the size and intimacy, and the modesty of it. When I was in my teens I got up on stage and I was paralysed by stage fright, I don't know how I managed to even get a sound out before that huge audience of about seven people gawking at me . . .

But if you go onstage with a guitar there's something which says, 'Impress me' . . . not just in the audience but something inside you. You think, 'This is a serious instrument that makes a lot of noise and it's got great deal of physicality' and when you hit a note that hangs around.

But when you play the ukulele it's a bit like feathers blowing off. People say, 'Did I hear a note? Probably not'. So it's the modesty that gives you a kind of confidence to be able to pick it up and shyly explore it.

Also the fact is was so intimate. You

could just sit there and cuddle it on the sofa, which is hard with a

big guitar and almost impossible with a cello or piano.

Also the fact is was so intimate. You

could just sit there and cuddle it on the sofa, which is hard with a

big guitar and almost impossible with a cello or piano.

And the neighbours don't complain, and that's important in an urban setting.

I remember once I'd borrowed a banjo and was trying to learn that and all the neighbours complained because it was too loud.

Have you always been a musician, but not one playing in the public domain. Because until now I only knew you as a journalist.

Yes, everybody does and there's that old cliché which has a lot of basis in truth, that all music journalists are failed rock stars. They all harbour the inner feeling they should be up under the spotlight and the microphone is there for them.

There is some element of that but not everybody has the drive or personality or talent to be a rock star, or can do what it takes to become a successful fulltime musician.

I realised after that first incident there was no way I could be a performing musician. And the songs I was writing at that point, if I ever heard one of them now -- thankfully there wasn't You Tube and all the cassette tapes have shriveled up thankfully, because the songs were all dirges in minor keys with lyrics ripped of from The Prophet or Herman Hesse books, as teenagers were doing then. Catcher in the Rye too.

Going into music journalism came about because . . .

What happened in a moment I think was great maturity -- but in retrospect was absolute immaturity – was I thought I was going to have to get a job because I was going to leave my teens. So I made a list of all the jobs that I wouldn't do. I wish I still had that notebook because every time I thought of a new job I'd think, 'No I couldn't do that' and I'd add it.

In the end there were about three things left: musician and that got crossed off; writer, and I hadn't thought about writing about music at that point; or spy. Because I liked doing crosswords and speaking foreign languages and so I thought, 'I could be a spy'. But that was a question mark one.

So obviously the thing to become was a music journalist which was made for people with my kind of mindset.

Although some people might say music journalists are spies too.

Yes, we are very nosey for certain. But it fitted me perfectly and I've loved being a music journalist during many decades now. Three and half, maybe even more . . . but we won't talk about that, give me a little mystery.

I'm very happy writing books about musicians too, and even my short stories are about musicians. It was what I did and the music kept on trying to come out . . . and eventually it did.

One of the things I've always found about music journalism is music is constant flux and change, so every day there is something new to discover or learn about. I find that exciting. It's like going to university every day.

Well, my idea of being a student was to take every drug that was available and get really high and noodle on guitar. I'd think what I thought then were deep thoughts, but forget to write them down. You're right about the constant newness, especially in English-speaking countries where it's almost like a chocolate factory with a conveyor belt of wonderful things you can pick off and gorge yourself on.

It's a lust for music that I always had and still do.

Are you as excited now about the music scenes, because there has been so much balkanisation of genres. There's never going to be another Beatles which unifies across styles and even generations.

There are individual things I get excited by. When I was a kid in London we only had two television channels and so everybody watched the same programmes and everybody would talk about what was on, be it Monty Python or Z Cars or Coronation Street.

So music seemed the same thing. I wasn't in my teens when the Beatles came out but I was a little kid who loved music so I was what my friend called “Beatle-damaged”, because I was totally in love with them. So I listened to every other British band that came along, and then Americans seeped into my consciousness. So there was never an effort to pursue these things because it was all just on tap for me as an inner London kid. And I could sneak out the house and see these bands.

It's hard to keep that excitement in later years because you do have to make a living. That's the boring part about getting older, don't like that one bit.

But I come across albums by people that I will put on over and over. That's the same with my old albums too, like recently with George Harrison's All Things Must Pass.

Yes, because it has just been reissued.

Yeah, so I went back to play the original vinyl. I got into that really obsessive rock journalist mode listening to hear discrepancies between one and the other. And it does feel obsessive. It wains a bit but for most at a younger age than me. I'm trying to do a Benjamin Buttons when it comes to my life. Becoming the music artist at a time when most people are probably not becoming a music artist.

Let's talk about the album then. All

that time with Mr Cohen must make you think very carefully about any

lyric you might put into the public domain. Have these song been

around for a little while?

Let's talk about the album then. All

that time with Mr Cohen must make you think very carefully about any

lyric you might put into the public domain. Have these song been

around for a little while?

The oldest one is from 2007 and that's You Are In My Arms, the one that sounds slightly Hawaiian with a sort of beachside but sad feel to it. A sweet whimsical feel.

The newest was written about two months before I went into the studio and that was Life Goes Bad When Love Goes Wrong.

They all have long titles or slight melancholy and wistfulness, the feeling of something lost and gone.

So they just date from when I got my ukulele which was 2006 and the next year I was writing songs on it.

And refining lyrics then?

I think when you are a music journalist or writing books, it's very easy to separate things and put barriers between you and people. It's the only way to exist. When I was doing the Leonard Cohen book, that was my entire life.

It was eating, drinking, sleeping Leonard Cohen and in some bizarre kind of way trying to live in his head. You are constantly going at speed through his past, meeting people who knew aspects of him from childhood on. So you really start to understand in some way, or feel you do, his motivations and feelings.

But once that was done those dreams didn't recur and I've not thought about his songs as being anything other than his songs and songs that I sang.

And my lyrics didn't seem to reflect that, except for one song maybe and that was The Rose You Left Me. I left the demo version version on the album on which I overdubbed a keyboard ting.

That was written when I was walking up a little hill near where I live in San Francisco – a city full of hills – and suddenly the words came and I thought it sounded like a prayer. And I don't usually walk around thinking up prayers. I thought i'd been Leonard Cohen-ed.

As much as I hear Americana in it I also heard what I loosely call Anglofolk, influences from Nick Drake, Sandy Denny and so on. I imagine they were people in your record collection when you were living in London?

Nick Drake certainly, because anybody who had just died or looked about to do from some unhappiness was somebody I was innately attracted to. Not so much folk though, it wan't until I moved to America in 1977 that I really started to listen to and have an appreciation for folk. Because I realised I liked Americana music and even some country bluegrass . . . but not folk, which was pretty much the same thing.

There was something about it being dragged across the Atlantic and taken up and down the Appalachians which gave it a sense of space it didn't have in England. To me folk music there was what we learned at school. We learned country dancing at my girls' school and that probably ruined me for life, I can't dance with a boy anymore.

And all these folk songs were foisted upon us, we had to sing Raggle Taggle Gypsy Oh and I had an allergy to folk music until it got really weird and hippie. Then I thought it was quite nice. It was when I came to America I started appreciating Sandy Denny from Fairport Convention and Pentangle and all those bands.

I had exactly same aversion, it all seemed worthy and earnest and finger-in-the-ear.

Finger-in-the-ear, exactly! A very affected voice, because no one sings like that, that nasal thing.

This is why A Might Wind is one of my favourite films, along with Spinal Tap.

A Mighty Wind was a very fine film, it's nice when pomposity gets punctured. And that's a very British, Australian and New Zealand thing, taking that pin to the bubble of pomposity.

I have to say it's a lovely and understated album, and quiet is such a nice thing to be reminded of in a very noisy world. I want to ask you about the journalism thing though. I drew a line a long time ago when interviewing people, and that was I never thought musicians were my friends but that I was there as a professional writer getting whatever the story might be.

When people said I was a failed musicians I would happily and truthfully counter saying, actually I was a failed writer. I wanted to be a better writer not a rock star. Is it important to befriend people in this game but not actually be friends?

It's a very strange sense of protocol. If you tried to sit down and articulate it, it would be like the mandarin courts of the past where nobody ever knew what the rules were but if you crossed them you'd be hung, drawn and quartered.

I think there is a natural tendency to detach yourself from it. When I got into rock journalism in '77 a lot of the journalists had the reputation that they were one of the gang, just a different kind of musician. They would dress up and look like the rock stars . . . and I guess I fell for that a bit in the beginning.

As to musicians who became my friends there would be a few who are big names, but when I knew them they weren't. They were people I knew early on in my career. Sometimes with people that you see and interview over the decades there is something like a friendliness. You are interested in each other and catch up . . .

But then you put that aside and get to the bare-knuckle boxing that it comes down to: they want to tell you one thing and you want to get another so somehow you have to get to that compromise. But it is strange that sense of protocol.

A lot of musicians at the middle level who have been around a little while but haven't broken into huge stardom have become my friends. One of those was Howe Gelb who I think did wonders with the album.

I spoke to Howe about two years ago at great length and felt I was just talking to someone who was a genuinely nice guy. He was in that middle area and very nice indeed.

I think partly for me it was because many years ago with the Americana thing, maybe in the mid Nineties, I instigated an Americana column for Mojo and put lots of these people in . . . and over time they learned to trust your judgement. You gradually gravitate towards each other.

I didn't want to do an album that had all my famous friends. I blush now at the thought of having made an album . . . but I would crawl into a corner and die if I had Robert Plant on backing vocals, Lard Ulrich on drums! That would have been creepy.

Leonard Cohen gave you an astonishing

gift of all access then leaving you alone. You must have been

subsequently approached by others to do a book on someone else. Would

you need to have that much freedom now to entertain it?

Leonard Cohen gave you an astonishing

gift of all access then leaving you alone. You must have been

subsequently approached by others to do a book on someone else. Would

you need to have that much freedom now to entertain it?

I don't write that many biographies and usually I take a big break and go back to the short form which is journalism and my short stories, which is like cleansing your palette for a while.

But in my world when you are writing about a person it has to be because you are somewhat in love with them, somewhat obsessed with them. It's not like I would knock on Leonard Cohen's door, which he would probably open, and go in there and live with him. It's more that I want to find out about this person and that I can't find that out in other books about them.

For example Bob Dylan. I'm fascinated by him but there are so many great books on Bob Dylan that I don't think there is any need for me to write one. I've read all the others.

So with the people I've written about . . . And the time I wrote the Neil Young book, which I wished were longer but I was given a word restriction, Shakey the great biography by Jimmy McDonough hadn't come out.

So if that had been out out I

would have been quite happy not to write about Neil Young.

So if that had been out out I

would have been quite happy not to write about Neil Young.

Serge Gainsbourg? There there wasn't anything in English on him that was readable. So it's not so much the access but your own personal take on it.

If someone came and said, 'Hey I want you to write a book about . . .' I don't know, someone who is in the charts and has a lot of money, let's say Beyonce – and they were going to pay a fortune and you'll have all access.. . .

But you know, I don't really care. I've only got so many years on the planet so why would I want to spend that time learning about a person who doesn't fascinate me.

I'm sure I saw it mooted that you were approached to do Tom Waits.

It's true. I was approached by a publisher before I did the Leonard Cohen book and I said I'd love to . . . but I do know that Tom has always been anti the idea of books.

The access is interesting too: If you read a music biography and it's not good then sometimes it's the writer's fault, but sometimes it's because they can't get to anybody to find out what they want, because all the avenues are blocked.

If that's the case and you can't get your A-list then you have to go to the B, C or D-list and then you can get people who perhaps have an agenda who are telling you stuff that isn't true, or they have a different slant on it.

So to do it properly what you need is

exactly what I got from Leonard Cohen, being left alone and being

given access. The only thing I asked him first was if somebody called

him up and said, 'This women wants to talk, can we talk to her?' is

that he should think really hard before saying No. Then I'd need to

think really hard if I'm going to do this book.

So to do it properly what you need is

exactly what I got from Leonard Cohen, being left alone and being

given access. The only thing I asked him first was if somebody called

him up and said, 'This women wants to talk, can we talk to her?' is

that he should think really hard before saying No. Then I'd need to

think really hard if I'm going to do this book.

There would be a reason for me wanting to talk to them, I'd have chosen them for specific reasons. He came back he said he would absolutely not get in the way.

Would you laugh aloud if someone told you Van Morrison [who kept Simmons waiting four days for an interview before saying he wasn't ready] was going to give you full access and talk to you?

(Laughs aloud) Just about the Tom Waits thing again . . . I did some interviews with him for Mojo and he was absolutely delightful and opened up, and on the second one he gave me some homegrown tomatoes. There are only two people who have given me homegrown food: Tom Waits and Leonard Cohen.

I'd love to do [Tom] but at that point it was his wife who came back and said Tom didn't want to do it, and I would respect that. Because I don't want to do a shoddy book on Tom waits with no access.

And biographies are enormously time-consuming anyway.

If you do them right they are. It's very easy to toss out something. My first book was a co-write on Motley Crue and I think we did that in two weeks. It was fun to do but not a deeply heartfelt project. It was making money to pay the rent.

It must have been a peculiar and different experience being with Johnny Cash in his home for a week in his final months.

That was one of the most amazing

assignments I've ever had. And I've had plenty of amazing one. I

haven't had Van Morrison yet but it's okay, I think I'm over the pain

of Van now. If he wants to pop over for a cuppa I might have a few

words though.

That was one of the most amazing

assignments I've ever had. And I've had plenty of amazing one. I

haven't had Van Morrison yet but it's okay, I think I'm over the pain

of Van now. If he wants to pop over for a cuppa I might have a few

words though.

But Johnny Cash? I'd like to pretend – and he's not around so can't deny it – that Johnny got on the phone and said he wasn't doing well and his wife had died and he might have to go back to hospital and that he wanted to spend one of his last weeks talking to me.

That did not happen.

It was all arranged by Rick Rubin, the great producer who worked with Cash for the last 10 years of his life but whom I knew previously in his earlier incarnation as a heavy metal and rap producer.

We didn't have a close friendship but we'd call each other once in a while, and it was his idea I get together with Johnny.

Johnny very much loved Rick and it was an amazing idea. To be with The Man In Black having breakfast every morning … it was really something to have that closeness and sense of intimacy thrust upon me.

He seemed to enjoy having a voice around him in the house after his wife had gone. That is what I heard from his housekeeper, I would never be so bold as to say such a thing.

But apparently he liked to have somebody wittering at him.

Rick and I were working on the big box set and I was interviewing everybody Johnny had worked with over the 10 years with Rick [for a book], then when he died all these books were rushed out. So we couldn't face doing it, so it never came out.

A bad book can queer the pitch for a better book always.

It's difficult. But the biographer in a way exists in the story because you are the character who is the filter through which the story is being told. Clearly you are doing it with diligence if you are doing it properly, but you are also going in with an attitude.

You can go in with heart as in my case or there was that dreadful one on John Lennon which was done with weird spite.

My attitude is due diligence, so if I find something out I'm not going to hide it – pleasant or unpleasant – because it helps me understand who I am writing about.

There's always room for different books on somebody even though I've said I wouldn't do it myself because I'd be happy reading the other books. But there is an opening for other interpretations.

What I find interesting is that books about men are usually written by men, there aren't many women biographers and because of that they tend to automatically ignore the women in these celebrity men's lives.

Now in Leonard's case to ignore or belittle the influence of women in so many ways would take away a big chunk of the story. It's not a telephone directory of his lovers because don't have a big enough shelf for that one. It was kind of, 'Put your hand up if you haven't'.

It would be a case of using that to understand his motivations and work. It's part of the story, it's not the whole story but it's a part.

That's how serious biographers work in

the worlds of literature and art, so this is just applying those same

principles to the world of popular music.

That's how serious biographers work in

the worlds of literature and art, so this is just applying those same

principles to the world of popular music.

Yes.

What music are you listening to at the moment. Are you an iPod person?

I don't wish to boast, but I am probably a gold medal-winning technophobe. I do not like gadgets. I have an iPad but I keep it in a padded envelope and write everything on the envelope. I never lose the envelope because it holds an Pad which cost a lot of money. So it serves its purpose in a way.

Also I love to have some silence and if I go for a run I don't have music with me. I like to listen to music in my own head without it being plugged in.

Plus I really hate mp3s, I'm with Neil Young on that . . . they are the curse of humanity.

Right now I've been a bit lacks in listening to things. Last week I listened to quite a lot of new artists because I was writing my Americana column for Mojo, so I was going through quite a pile of unsolicited Americana CDs and seeing if anything jumped out.

But with music journalists, as you know, you see so much stuff that I think nobody is going to give an honest reply/ They will just deal with the last three things. It's endless, more than ever it's endless. There are no major labels filtering anymore.

And now I've added to this pile so I apologise. Mea culpa . . . but I did take a little longer to get there.

You are a late bloomer?

I don't think I'm a bloomer, but I am certainly late.

Jos - Dec 8, 2014

Yep,she sounds wonderful! love it.

SaveWayne - Sep 12, 2023

Great interview Graham!

Savepost a comment