Graham Reid | | 8 min read

Punch Brothers: Julep

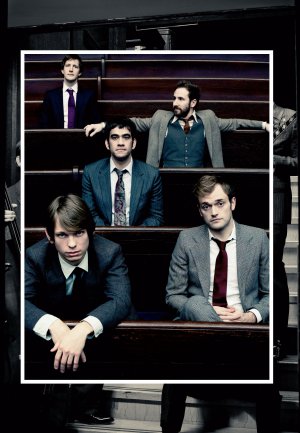

Towards the end of a digressive and interesting conversation with Chris Eldridge, guitarist for Punch Brothers, I ask if the description “bluegrass” -- which has most commonly been applied to their music -- has any relevance anymore.

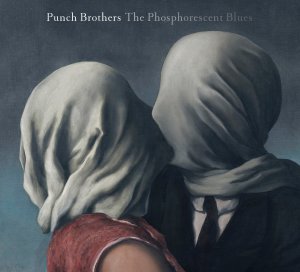

After all, they have edged their music towards art rock with classical references, have thrown in covers of songs by Beyonce and the Cars just for fun, and their new T Bone Burnett-produced album The Phosphorescent Blues opens with a 10-minute piece which – around the midpoint – morphs into something with layered vocals of the kind Brian Wilson might have dreamed up.

Elsewhere there is power pop with mandolins, a short interpretation (admittedly in a slightly bluegrass style) of a piece by Debussy and songs which bend and reshape themselves more like something from Radiohead.

Oh, and there is a broad very 21st century theme running through: the emotional and physical isolation from each other which modern technology like cellphones allow us. That's more Pink Floyd than Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs.

So Chris, that label of convenience “bluegrass” doesn't seem especially relevant and it seems rather limiting in terms of others' preconceptions of what it means.

Is that something you are happy to live with or has it ceased be relevant and maybe even a hinderance? Punch Brothers sound nothing like The Foggy Mountain Boys.

“I think bluegrass is a funny word and it means different things to different people. I personally don't mind that label. But I think it's just that, just a word. I don't think it means that much.

“I'm proud to be part of that lineage because I love bluegrass and string band music, and how vital and creative it has been throughout its history. People don't realise that bluegrass is only 70 years old, it's a very young music which has changed a lot.

“So in that respect if you look at it

as a lineage of musicians who influenced each other . . . Bill Monroe

influenced Sam Bush and he influenced Tony Rice who influenced Bela

Fleck who influenced us . . . so I am happy to embrace it.

“So in that respect if you look at it

as a lineage of musicians who influenced each other . . . Bill Monroe

influenced Sam Bush and he influenced Tony Rice who influenced Bela

Fleck who influenced us . . . so I am happy to embrace it.

“That being said, I don't think it tells you much about our music to say 'bluegrass'. And that is where a term like that can be troubling because it can immediately put what someone's preconceptions of what it might sound like straight into a box.

“So all of us . . we don't love 'bluegrass' or whatever genre you can come up with. We just love good music. It's that Duke Ellington thing about two kinds of music, good and bad. We're all into good music and trying to figure out what makes good music 'good'. And all music is dealing with harmony, melody, rhythm and form essentially.

“In good music people use those building blocks to good effect and very cleverly. In bad music they don't. We want to make good music. That's the band's MO”.

Founded almost a decade ago, the band went through a couple of name changes before setting on Punch Brothers (a reference to ticket punchers on the railroad) and have been signed to the innovative Nonesuch label, home to many contemporary classical, jazz and world music artists as well the likes of Ry Cooder, Brian Eno and Nickel Creek (which includes Chris Thile, chief songwriter for Punch Brothers).

The Phosphorescent Blues is the band's fourth album and Chris Eldridge – their in-demand guitarist who founded the bluegrass band Seldom Seem and has worked with Elvis Costello, T Bone Burnett (who had them on the concert of Llewyn Davis music), Paul Simon and Del McCoury – speaks to us from his New York home.

Congratulations on the album and, I mean this in the best possible way, it's one people have to commit time to. Not too many artists open an album with a 10 and a half minute track.

Thank you, and hopefully we want people to have to take time with this. For all of us, the music that turns us on the most is the music you have to dig into and peel away the layers like an onion. With each layer something else new emerges. We always try to write music that will keep giving.

I will ask you specifically about some songs in a minute but I've read somewhere that this album was the result of writing retreats. If you do that you have to make time in a busy touring schedule and leave family and friends. Do you do that as a group or do you go off separately and bring ideas back.

I guess both of those things happen, but any of the real writing of Punch Brothers is written together. We are all sitting in a room together. That being said, certainly a lot of these songs started elsewhere where one guy would come up with something he thought was cool, but then it's a matter of presenting it to the band . . . and we all do that.

And the band will either latch on

collectively and be interested in that idea or see different

potential in it. The best songs come when something different is

discovered and is seen by the rest of the guys. The band can see

something different in the idea and maybe what it sees is better

because the person with the original idea didn't expand it beyond a

seed.

And the band will either latch on

collectively and be interested in that idea or see different

potential in it. The best songs come when something different is

discovered and is seen by the rest of the guys. The band can see

something different in the idea and maybe what it sees is better

because the person with the original idea didn't expand it beyond a

seed.

And so it's matter of finding the context for an idea in a song that is already written or an arrangement is not quite complete?

Kind of. Once we start working on a song we usually get single-minded and try and finish it.

This record was a little different because these writing retreats were spaced out and we now don't all live in the same town anymore, so we were not always able to finish a song in three or four days. Which was actually good because we'd have to leave and live what we'd come up with. That was very honest when you get to come up with something and reevaluate it from a more detached place further down the road.

We've never had that luxury in the past. Previously we've always been so under the gun between touring then having a few days here and there to work on something, we needed to come up stuff in that time.

We didn't have that constraint on us this time and we could let these things marinate and see if they warranted further development. There were some things we abandoned which was great because in the past we might not have had the courage to abandon them.

You've had a long association with T Bone. What is his role: does he facilitate, does he just let you do it or is he hands-on?

T Bone is very interesting. As far as dictating musical content he's very hands off. Some producers get in there and have ideas and toss them out. T Bone doesn't do that. What he does do, and does it more brilliantly than anyone I've ever seem, is he gets everyone in the room to be their most relaxed selves.

That is so important when you are recording music, because you are trying to capture more than notes that are in time and in tune. A sequencer on a computer can do that, but nobody really wants to listen to that.

What you want to capture when you record is humanity, the soul behind the people in the room playing it. And that always happens best when everyone is feeling unafraid and forgetting the red light is one.

T Bone is such a kind, smart, funny, warm and knowledgable guy that you really feel like he's taking care of things. There's an overview he has and you feel that everything's going to be okay. Any angst you might have is not there with him.

It's very rare. More rare than you would think.

I'd like to ask about a few things

specifically. I love the opener Familiarity, it's a challenge for

people as an opening track but there's a beautiful passage just

before the middle in which I heard Brian Wilson . . .

I'd like to ask about a few things

specifically. I love the opener Familiarity, it's a challenge for

people as an opening track but there's a beautiful passage just

before the middle in which I heard Brian Wilson . . .

Yes.

But I also hear this repeated figure all the way through that which is very like Steve Reich minimalism at the same time. Where does that stuff come from in band, they would seem to be disparate elements but they work perfectly. Was that spontaneous?

More than any of the others songs, just because it is so long, Familiarity was written and really sketched out in advance. A lot of the others songs developed more organically in that you come up with a verse which leads to a certain chorus, and then it's just a matter of arranging, putting on your bells and whistles and maybe other structural concerns. But the nuts and bolts are there and it's just a matter of finishing it.

But with Familiarity it was a lot more conceptually driven as far as wanting to paint a scene and tell a story, and in the second part the narrator doesn't know if he's in dance club or a church.

So there was more of a sketch on that where we wanted the three sections to have an arc to tell the story.

As far as how the individual ideas come . . . that's a hard thing to talk about. As a performer you just to have to close your eyes and think, 'What would I really love to hear that I might not know how to do? What needs to happen now? What would be cool if I was listening to someone else's record and I heard them do this, what might they do?' So a lot of ideas come from taking yourself outside of your normal process.

At the other end of the scale you have I Blew It Off which sounds to me like a great power pop song with mandolins. That's a sharp and economic song, and you have the bluegrass Bo Weevil in there too. When you are sequencing the track order you must think about what to place before or after something else to make sense, or even just to mix up expectation.

Definitely. Sequencing is a big deal. Albums are not as relevant as they used to be and a lot of people don't consume albums in a sitting as they maybe once did. So we were thinking about that and wondered if it mattered and did we really have to nail a sequence.

But with this collection we felt that the sequence was going to be of vital importance in telling the narrative of the whole record and we wanted it to be a coherent 'album'. So that was probably two weeks of back and forth e-mails and all of us just working on figuring out general trends of how we wanted to start the record, how to keep the flow going for a listener so one song lead into the next.

There is a thematic link across a number of songs, the idea of emotional isolation which technology allows us today. Was that an idea you were thinking of independently or was it something that emerged when you sat down to think of an album and were looking at its overview?

It came about as a result of

conversations so it was something that was on our mind. A lot of

times we work on the music first so the words are really more Chris

Thile's domain, but the band definitely has a veto power.

It came about as a result of

conversations so it was something that was on our mind. A lot of

times we work on the music first so the words are really more Chris

Thile's domain, but the band definitely has a veto power.

The whole idea of isolation because of devises, and this weird electronic reality we live in, was something we were all thinking about and wrestling with. So it was, 'Let's talk about that and see if we can organise around that thing'. We'd never really had A Theme at the centre of a record like that before. Our past stuff has been a lot more personal.

And that's a Rene Magritte painting on the cover, which sums up so much of that idea in one image.

Yes, exactly right.

post a comment