Graham Reid | | 15 min read

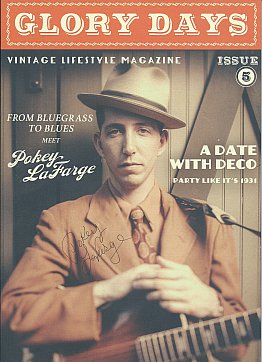

Pokey LaFarge: Underground

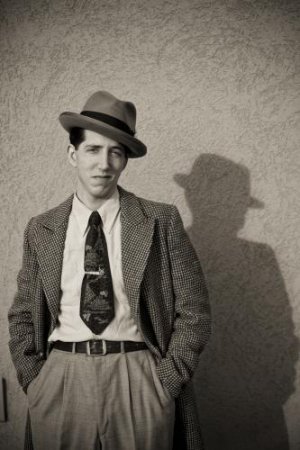

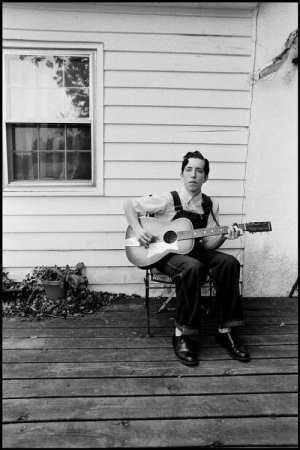

In a stylish blue shirt buttoned to the neck and topped by a red neckerchief, blue dungaree jeans with turned up cuffs above his sturdy and well polished lace-up boots, Pokey LaFarge cuts a very interesting figure in this downtown Auckland hotel room.

He may look like someone from the better-scrubbed end of the Thirties – and his music certainly steeped in traditional jazz, ragtime old blues and folk – but LaFarge (real name Andrew Heissler) insists he is very much a man of this time.

However he looks to the past, not just as an inspiration, but because knowing your history is important. And, as we shall see, he not only knows his but – despite loving his country and being a great ambassador for it – finds to many of his fellow Americans don't.

“I love my own country, not for its politics but because I think it's the most beautiful country in the world.”

But then again, LaFarge – brought up in and around St Louis, Missouri in the Midwest where he still lives – is very different.

He has been to New Zealand before (an extensive tour and a hit Womad appearance in 2014) and is glad to be back because the landscape here reminds him of the Pacific Northwest which he loves. And how mellow the mood is in both places.

On this day he's had an early start – up at 6am for a National Radio appearance, “I was up before I was up” – and although pale, he warms to a lengthy conversation.

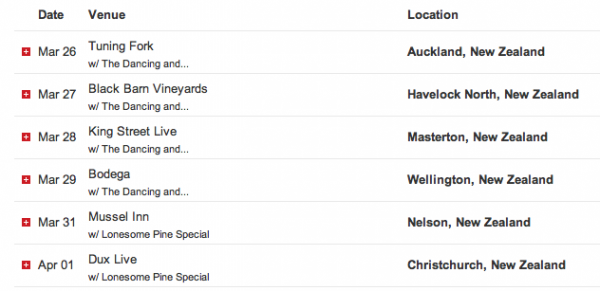

The day before out chat – tonight he

plays an already sold out show at the Tuning Fork just down the road, other dates below – he has had a

soundcheck with the band and that's been important because they are

airing many of the songs from his new album Something in the Water,

much of which he wrote on the road last year. But they have had

little time to work them out live.

The day before out chat – tonight he

plays an already sold out show at the Tuning Fork just down the road, other dates below – he has had a

soundcheck with the band and that's been important because they are

airing many of the songs from his new album Something in the Water,

much of which he wrote on the road last year. But they have had

little time to work them out live.

So Pokey, often you wouldn't have a chance to do a soundcheck, or someone would do it for you . . . the the first time you see the stage and venue would be when you walked on?

“That's for the big timers,” he laughs. “I'm a middle man. Our crew sets up but we do a final sound check and my guys are pretty specific about stuff so they want to be part of it. We have roadies but a couple of the guys don't even like their stuff to be packed up because they have their own way.”

Our conversation starts when I ask him about where he's from and how being in the Midwest has shaped him as a person and an artist. I say wherever I travelled in America I am struck by how many separate Americas there are, each distinctive. So what's distinctive about St Louis?

“St Louis may not be the capital of the Midwest – that would be Chicago which is five hours north, and I grew between in the cornfields of Illinois. Chicago is the economic centre, known as the City of Broad Shoulders, the Hog Butcher to the World.

“St Louis during the riverboat days used to be the second biggest city in America until the industrial revolution. Chicago is built on a swamp so it's amazing it is the city of skyscrapers.”

He notes that Chicago, St Louis, Detroit, as far east as Pittsburg, Gary in Indiana and Dayton, Ohio are the geographical center of America and this region was the centre of industry in America.

“In a lot of ways they built our country with super-capitalist ideals. But America has be de-industrialised since the Seventies and we started focusing on world economics. So the Midwest started to decay.

“But that way of life is still there. It's in our roots and only a generation apart. And we are living in this abandoned museum. The beautiful architecture is still there. The abandoned buildings and factories you see has an effect on you.

“We can see what we came from and it's almost a sign of America. And you see where we are now and not in a negative way. What I am most excited about is the Midwest has always been an important part in the foundation of America and it's going to be important to the new identity of my country, because the Old America has been pretty much taken away from us.

“It is dead and gone.

“We are living in an area which has a

lots of things that could benefit a new identity.”

“We are living in an area which has a

lots of things that could benefit a new identity.”

He doesn't

understand why more touring musicians don't live in St Louis: It is

five hours from Nashville, Chicago, Kansas City, Columbia,

Louisville, Tulsa, Cincinnati . . .

“Okay there's no industry, I

get that. But it's affordable. When you have a place that's cool and

hip and that's affordable, that's when artists come in. And when they

come in the money starts coming in. Look at SoHo in New York and The

Mission in San Francisco.

“I think there are great things ahead, if we can survive.

“But it's not a sexy a place, not a place that has tons of things going for it on the surface like LA, San Francisco, New York and so on. It's raw and rough around the edges . . . and that's what I like about it. That's what makes us what we are.”

He bemoans the lack of assistance for the rural economy, the embargoes put on farmers and investment gong offshore. This has marginalised regular working people – “and they are 99 percent of Americans” – and they have been abandoned by their government.

The music and family influences which shaped him – two grandfathers who introduced him to banjo and history respectively – have been well canvassed, but did the young LaFarge at school ever just listen to pop music like his peers?

“Duran Duran would have been a little

bit earlier than my day,” he laughs when I ask if he had such

posters on his wall. Nirvana then?

“That would have been more

junior high stuff. I was in junior high in '95 and '96, but by that

point I had moved on from pop music by about 13, all the classic rock

like Zeppelin. Although I loved CCR and they are one of my favourite

bands to this day.

“Within 10 seconds you are singing and playing air guitar.

“But I was being exposed to other things by some older people, like my grandparents, and I was exposed to history at a young age. I had it in me to appreciate that.

“My mum was really big into antiques, my dad was into repurposing old furniture because he was a carpenter. So that was in me, I was born with it. It was around me to appreciate where things come from.

“So naturally when I heard some of

this music, the classic rock stuff, I wanted to find out where that

came from.”

“So naturally when I heard some of

this music, the classic rock stuff, I wanted to find out where that

came from.”

Well, Led Zeppelin can be like a road back.

“Yes, but there have ben a lot of forks in the road. As Yogi Berra said, 'If you see a fork in the road, take it'. He's from St Louis.”

I congratulate him: last year he was inducted into his high school Hall of Fame . . . but he couldn't make the ceremony because he was touring so his tour manager filmed him making his acceptance speech while Pokey was driving the rig.

“You could see the road going by behind me. My dad was there to accept the award for me and when it came to talk about me the host speaker said, 'Now we don't advise anyone out there to do this' and the video of me was up there. The whole auditorium was laughing at that.”

Was he a different kind of kid in high

school?

“With kids it's always the things on the surface, they

don't so much care about what's underneath. I've always been kind of

an eccentric person and not just in the things I enjoy but what I

enjoyed very much had a connection to my outward appearance. I'm a

very expressive person so have always had an expressive style, a bit

louder and different style.

“High school no exception, so people could see me and go, “Freak!' . . . Looking back I know I had a lot of angst in high school like a lot of kids do.

“I certainly had big ideas and wanted to get the hell out of where I was living. But people were pretty tolerant of me. I went to a small school, a good school and very tolerant. I didn't do too good but some of my best friends today are kids I went to high school with.”

They might have moved out to Seattle, New York and Wisconsin and of course Chicago and other places while he has remained rooted in St Louis, but he sees them when on tour.

After high school he literally took to the road – “It was Kerouac's fault, I read On the Road when I was 14 and I got into John Steinbeck” – and he was already writing prose and poetry incessantly.

He recognised the inspiration writers got from traveling, American culture has a fascination with the highway, and writers like Mark Twain, Steinbeck, Kerouac and others were all traveling and talking about the big wide country that was out there.

The music he was listening to was the same.

“They were talking about this . . . this almost dream of America. I think my life is like a dream that I am chasing because it's not really reality in many ways. When you are out there living it, it's not nearly as exciting as when you are reading it.

“When you are sitting listening to Jimmie Rodgers who is like the Mark Twain in music, the idea – the idea, the masturbation – of it is a helluva lot more fun that actually doing it. You really have to love traveling.

“When you set out to something in your life you will accomplish something, and that builds confidence. That was something that I did not have in high school and I've since grown a lot of confidence . . . but it's something I struggle with. But then again I wonder if most people aren't like that, especially people who are creative and are put in front of a large group of people on a nightly basis.

“It's hard to get out of your own head.”

Did becoming Pokey LaFarge

help?

Did becoming Pokey LaFarge

help?

“That's an interesting question,” he says then leaves a

long pause while he considers it.

“It's hard to say because I was Pokey LaFarge before I was ever successful, for a long time before I got anywhere. I'd already seen and done a lot until that time.

“The deeper parts of that question I could answer but some of which I don't know if I possibly could at this time. Maybe that's a chapter I have to save for my biography.

“If I could just clarify though, I

don't think it's an alter-ego, it's just a name. I've worked very

hard to have transparency in my life, so it's just me and the world.

And to be honest with myself and the world. Because you could very

easy get lost if you are acting all the time.”

I've never got

the sense you are acting Pokey LaFarge and that's who I'm talking to

now, and that when you walk out that door you become someone else. I

see you as exactly who you are.

“Yeah, I've definitely had – more often than not through media, and I guess media is somewhat an extension of the general public – conflict because to them some things, the larger picture being comprised of something like historical things – has affected that relevance.

“Part of that could be my fault but I've learned I have to craft things I want to say in my own unique way and how I talk about that past, and its importance to me and to the world.

“We have always lived in a world, but perhaps more so now, that couldn't give a damn where it comes from. People don't care about the past, especially in America. There's no emphasis on the past, they don't teach history very well in the States. People don't know who the fucking president was in World War II.

“People think we were fighting Russia or something, that it was the Cold War.

“It can be frustrating because you see how these decades come back, like how kids now are dressing like the Nineties or the Eighties.

“Now that's funny that you have all these psychedelic rock bands dressing like the Sixties. But that doesn't get talked about the same ways as with me and a somewhat more vintage style. Because [what I do and how I look] is not hip, it's not a fad to large numbers of people. If it was, then it might be more appealing.

“So its more of an uphill battle for legitimacy for me.”

People mistake you for someone nostalgic for a world you never knew, but I hear you as a contemporary artist just using these musical idioms.

“I do feel a connection to all those people out there who are underdogs. I come from an underdog place and I live in an underdog place. It's the people who don't get recognised. All those great humans out there who just go about their business and don't get recognised, specifically all those great artists alive today and all those from back in the early 20th century.

“We have always been fighting for

recognition: country music, jazz, blues . . . they have never been

accepted by the general public. It's always minority music.

“We have always been fighting for

recognition: country music, jazz, blues . . . they have never been

accepted by the general public. It's always minority music.

“For every Hank Williams [right] there are a thousand others you've never heard of, for every Louis Armstrong there were a thousand other people who starved to death playing jazz in New Orleans. I feel a connection to that music and those people, and have for a long time.

“More so than to music today, but

I've become more open-minded and am realising how similar it all is.

My music is not that different – but is totally different, but

it's always the subtleties. And you almost have to tell people what

it is, and what it's not.”

He finds it hard to tell people what

it's not and what he'd rather say is what it is.

“What it is, is it's me. I am being the person that I want to be, I'm making the music I want to make. I'm not consciously not making something.

“I'm making music that I want to

listen to. I don't know if I've done a very good job with it,” he

laughs, “ but I actually think this new record is the only record

I've made that I actually want to listen to. I think I'm coming into

my prime.”

And what is Pokey LaFarge music?

“It's music that has a good groove, strong melodies. I do think that's a thing lacking in a lot of music and that's unfortunate. I think there's also no longer an emphasis on musicianship, it's all electronic computerised and that's just sad.

“It's taking the music away from the heart and the human . . . although there is great electronic music of course.

“Also harmony, which solidifies and enriches the melodies. And good honest lyrics. For me folk music represents where that person is from, for me that's what folk music is. It puts it in a place, and that's what music used to be.

“But then with radio talking over and becoming global – and in a lot of ways that's great – but I feel it's important to talk about where I am from.”

Our talk turns to his new album Something in the Water. One of the many standouts is Underground, an almost apocalyptic story of Nature rising up to put us in our place.

“Cool, that's one of my favourite ones. In the States – a huge country – let me just give you the rundown: tornados, floods, earthquakes, forest fires, inland hurricanes, blizzards, black ice . . . So I wrote it because those things were all happening at the same time. Forest fires in a late summer after it's been dry for a long time, tornado season waning but still happening, hurricane season coming on . .

“I thought it was just all happening. But there's also a major faultline in America that goes right through the Midwest so like I was saying in the song, 'When the New Madrid Line breaks apart' that's it, it's connected to the San Andreas Fault in California so when that goes they say LA and San Francisco will separate from California. Another Christchurch maybe.

“The other things I was trying to say more subtly was the things that are happening in the underground, can't you hear that sound. The things happening below the surface, musically and socially and whatever.”

And Goodbye Barcelona?

And Goodbye Barcelona?

“Oh, you

like the minor key songs” he laughs. “It's my own bastardised

version of a Spanish-type tune and it's a waltz, although the last

time I checked I don't that there's too many waltzes in Catalan. It

was written in a hotel room in Berlin a couple of days after I'd gone

to Spain for the first time.”

He recognises people outside of America get him in a different way than those in his homeland, perhaps because the appeal certain parts of American culture has. It's the highway, the expansive country, cowboys and so on, and perhaps her represents a certain type of America to them, he thinks. Maybe?.

Maybe they see and hear an older and more stylish and honest America that he represents?

He notes that there is a certain respect from his fans for the way he carries himself and what he says, “but there are definitely some things in my life and music that are much more tangible [to them] than in a lot of today's pop music. That itself is what I am striving for; timelessness and quality”.

And that he speaks from his own time and place, because how could be do anything else.

“For me to make processed music would be the same as saying I support work and labour in America going off-shore, supporting sweatshops. You don't get the same quality, it's unethical . . so the music is the same. And food. How is it produced and how people have accessibility to it. I'm starting to fight for this more and more.

“This goes back to the honesty and transparency I want to have. Music is just an outlet, but it is connected to things deeper.”

He writes prose (“I don't have time to finish anything . . . I've got rusty”) but can write songs on the road and gets inspiration by being out there and moving all the time.

“I'm getting all this stimulus but I find I am scatterbrain. I have the stimulus and am pouring a lot of stuff out, but you have to focus to finish. Finishing songs doesn't happen for me on the road, I just get pieces and frameworks.

“Some do in 15 minutes flat, and those are the best songs. Like The Spark off this new record. I woke up with that at four o'clock in the morning. But I have five different notebooks and notes on my phone.”

Our conversation tuns to other songs on Something in the Water, notably the ballad When Did You Leave Heaven which is very much in the tradition of old love songs.

He concedes immediately it's an old Tin Pan Alley-type tune and it is simply an A-A-B-A structure. But, as was common in many early songs, there is a verse at the start before that pattern enters.

“This was very popular in many early tunes but when it got moved into jazz and early pop tunes they would take that introductory verse out. Stardust had a verse, only at the beginning.”

And Route 66 and Bye Bye Blackbird, but most people never sing that first verse. McCartney did on his Kisses on the Bottom album tough.

“No, and that's why I like to write songs like that.

“The inspiration for our background

singers is important though. Certainly with a song like that and

thinking about that era, you'd think the Mills Brothers would have

been a good way to go. But our inspiration throughout the whole

record was the Jordanaires, they did all the Elvis stuff and all the

country singers, Patsy Cline, Johnny Horton . . .”

“The inspiration for our background

singers is important though. Certainly with a song like that and

thinking about that era, you'd think the Mills Brothers would have

been a good way to go. But our inspiration throughout the whole

record was the Jordanaires, they did all the Elvis stuff and all the

country singers, Patsy Cline, Johnny Horton . . .”

One of the first records I ever bought was a Johnny Horton [right] song.

“You serious? Man. I love Johnny Horton and not just his patriotic tunes. People don't realise he had a slew of great rockabilly and country times.

“He had an interesting life story and they should make a movie about him. He was really into death, the Ouija board and all that. He predicted his own death and knew exactly how it would happen. And it happened.

“And hey, you know all those songs Hank Williams wrote about Audrey, all those songs about how his woman was putting him down? When Hank died she married Johnny Horton, when Johnny Horton died she married another guy . . . and he died.

“Three husbands. She was the Black Widow, man!”

POKEY LaFARGE NEW ZEALAND TOUR

Mike Pearson - Mar 31, 2015

Interesting. Modern but old rythem and blues and sounds quite vintage. Need to investigate more.

SaveTony Walker - Apr 7, 2015

Good article, Graham.

SaveReally like the vintage feel to this guys music. Gonna check out the album!

post a comment