Graham Reid | | 15 min read

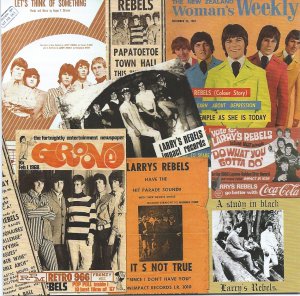

Larry's Rebels: Let's Think of Something (NZ version)

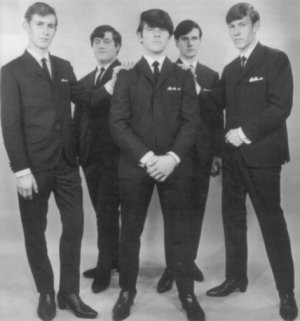

The guy who had the best seat in the house to watch the rise of the Auckland rock band Larry's Rebels in the Sixties was Nooky Stott. He was the group's drummer and a child of Fifties rock'n'roll.

“I lived in Ponsonby and our local picture theatre was the Britannia. I think I saw Rock Around the Clock and Don't Knock the Rock at least 10 times,” he says.

Stott – Dennis before the nickname stuck – was in the schoolboy instrumental band the Young Ones playing Shadows songs in '62. The band turned into the Rebels, then Larry's Rebels when singer Larry Morris joined two years later.

Stott was there for the whole ride of hits, traveling New Zealand on package tours with the likes of the Eric Burdon, the Yardbirds, the Walker Brothers and Roy Orbison, and in Australia opening for the hugely popular Easybeats.

He was there when Morris quit in '69 for a solo career and they subsequently had a number one single My Son John with Glyn Mason as their new singer.

He was there when the band slowly

pulled apart in early '70 in Australia after which – as he says in

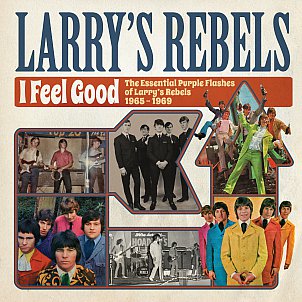

the liner notes to the new I Feel Good CD collection of Larry's

Rebels – “I ended up living back home with Mum and Dad with 50

bucks in my pocket, a pair of drum sticks and a suitcase full of

stage clothes”.

He was there when the band slowly

pulled apart in early '70 in Australia after which – as he says in

the liner notes to the new I Feel Good CD collection of Larry's

Rebels – “I ended up living back home with Mum and Dad with 50

bucks in my pocket, a pair of drum sticks and a suitcase full of

stage clothes”.

It had been eight years of fame and a fund of great stories to tell, but also time to look for a job and get some order -- and money -- into his life.

“I had a lot of regrets, but you've got to move on, don't you?” he says.

The stories come back now with the CD and a vinyl album of Larry's Rebels to be releases on Record Store Day (see here), and Stott – now semi-retired from the business world but playing again when it suits him – admits he's not so great with names but remembers events pretty well.

“Through a bit of luck I lived my life backwards,” he laughs. “We were tripping off to Australia when I had just turned 15 . . . so I lived my life up then. Now I'm happy not to be scooting off around the world because I've been there and done that.”

Stott says that when he was in secondary school – Auckland Grammar – he was interested for the first couple of years but then was constantly getting his hands and knuckles rapped by teachers' rulers because he was constantly tapping his hands on the desk.

And things outside of school were kicking off for him, even as a very new teen the work was coming in for the Young Ones.

“Mum and Dad said they knew what was happening and weren't going to stand in my way, but I had to get my School Cert first, so I hung around and did that.”

He laughs about how the school principal Henry Cooper would run a cane across the back of his neck and say to him “Stott, just because you are a bloody musician, or think you are, doesn't mean you can break the rules”. So he would have to get his hair cut.

One day Cooper was signing the absentee notes and Stott had taken two days off for the first television show Larry's Rebels: “He said to me, 'This says you were sick' and I said, 'I was'. He said, 'How sick were you? I've had information you were in the television studios' so I said, 'Yes I was sick, sir. I was sick of school.'

“From that day on he knew I had my eyes pinned on where we were going. It got to the stage where he's say he'd seen me on Happen Inn or whatever it was.”

For the boys in the days before Morris joined there was plenty of work. Stott says the parents of 13-year old guitarist John Williams, keyboard player Terry Rouse and bassist Harry Leekie realised they couldn't stop what they were doing so it was better to control it.

They were offer the chance to play in a coffee lounge on Queen St and would finish at 10.30, so a parent would come and pick them up.

“Unbeknownst to us it was a strip club as well. But all the girl did was take her top off. At the 13th hour one of the parents found out so put the brakes on, but felt they couldn't stop it so we went ahead and did it.

“The funny part was that here's John Williams who was 13 at that stage and this chick turns around facing us and winks at the band, unbuckles her bra and takes it off and turns around to the audience, then she swings her bra over John's guitar . . . which went upright!

“That was our introduction to the nightclub scene.”

They were primitive days: In some of the early photos they have wooden mike stands with the top whittled off and tape wrapped around to hold a mike. And “my first PA was a 10 watt amp going through a 10” speaker”.

They played local halls, dances and churches and met Larry Morris when they backed him on a couple of Cliff Richard songs in a small studio.

On the way home in the car Morris asked

what they were doing on Friday, they told told him they were playing

St Martins in Mt Roskill and on the night he walked in, joined in and

. . .

On the way home in the car Morris asked

what they were doing on Friday, they told told him they were playing

St Martins in Mt Roskill and on the night he walked in, joined in and

. . .

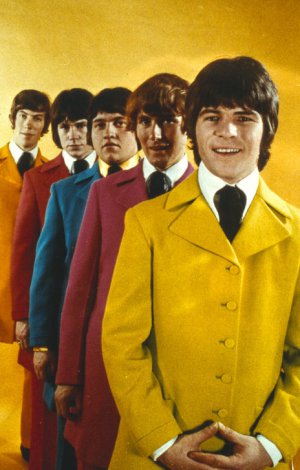

Larry's Rebels were born in early '65, and the music scene was changing rapidly. The Shadows were being eased out and the Beatles, Stones and Who were all powering through.

The group covered songs by the Who and the Small Faces –It's Not True and Whatcha Gonna Do 'Bout It appears on the CD compilation – although Stott says all the way through the transition to tougher sounds there were songs by Buddy Holly.

“We had to change. The way I see it was there were the Shadows and a lot going on with Elvis Presley in that early time . . . and nobody wanted to take [Elvis] on or even play that sort of thing. Then we started doing a few Cliff Richard songs which was ideal for Larry, then when the Beatles came along we started to develop into that.”

He thinks back on those days playing in Auckland clubs like the Platterack and Top 20 as simply exciting and bit innocent. He refers to the recent tele docu-drama about Cilla Black's rise to fame in Liverpool.

“That really caught the excitement of the times, everybody was going to make you a star. That pure excitement with the kids [in the programme] I can relate to because that's what used to go on in the Top 20. During our residency the idea came up about putting lunchtime sessions and they really took off.

“We did that four or five times a

week plus we were working at night."

“We did that four or five times a

week plus we were working at night."

By doing that the band had to build a repertoire and learned how to relate to an audience.

“If you know that four or five night a week you are going to be entertaining people, and in a lot of cases those people would come back the next night, then part of the agreement we had [in clubs] was we had to learn three or four songs a week to keep up with what was going on.

“You'd look at the records coming in for the week and there would be Gerry and the Pacemakers, five by the Beatles, two from the Rolling Stones . . . You would go through and pick the most appropriate for the venue and the band.

“But it never felt like work, it was just exciting and the hours flowed by . . . and at the end you'd think you'd had a bloody good time but didn't make any money!”

The band's classic hit was I Feel Good, a toughened up version of a song by Britain's Artwoods which Stott heard on shortwave radio.

“We used to hook on shortwave radio and there was programme coming out of Germany that was broadcasting to all of Europe but doing it all in English. Their music was a bit more aggressive and out there. I think I got the tail end of the song and for a couple of weeks tried to get it all, and ended up getting about half of it.

“So we put it together and I don't know how we got the whole thing . . . maybe [promoter] Russell Clark got it through the recording company.

“I recall we didn't hear the Artwoods

version until we'd finished recording it.

“I recall we didn't hear the Artwoods

version until we'd finished recording it.

“Another like that was Mo'reen. I heard that in Australia and I remember saying to the guys I had the chorus but I didn't remember what the verses were.

"We actually started playing it on stage in Australia. It wasn't until about 10 years ago I found out it was originally done by Paul Revere and the Raiders. Terry Melcher wrote the song and I went through all the stuff I had by Paul Revere and couldn't find it, but through Uncle Google I picked it up.

“I tell you what, we were pretty close to it and I might be a bit biased but I think our version has a bit more meat to it, because we made it a bit more bluesy than Paul Revere did.”

Stott says he is very pleased by the sound of the new compilation because the songs now appear at the speed at which they were recorded. For many years he's been unhappy with reissues which have appeared because back in the day the songs would be mastered just a little bit faster and over the years that paced just picked up steadily.

Radio Hauraki, he says, told bands to keep songs no more than 2.20 seconds but would ask the studios to master them faster so they were even shorter. I Feel Good is an example of that.

If a song is sped up and loses 10 seconds, multiply that by 24 songs and you get four more minutes of advertising time. And what was recorded in C is now heard in C sharp.

“But for the CD Simon Lynch has done the mastering and I had a good listen and said to him he'd done brilliant job.

“There were things I did which over the years had been lost but he brought a lot of that back, in particular with I Feel Good. He's given it quite a bit of punch and you'll find the snare is crisp and driving.”

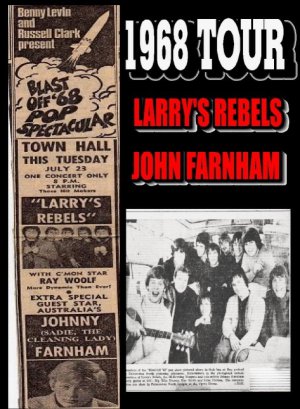

Recording was fitted in around

relentless club work and tours with local artists on Loxene Golden

Hits packages (Mr Lee Grant, the Chicks etc) and with the likes of

Johnny Farnham (then a chart-topper with Sadie the Cleaning Lady and whom they got into soccer), the Yardbirds (then featuring the little known Jimmy

Page playing guitar with a violin bow) and Tom Jones . . . who was so impressed by them he brought beer

backstage and sat with them until he got called to do his set.

Recording was fitted in around

relentless club work and tours with local artists on Loxene Golden

Hits packages (Mr Lee Grant, the Chicks etc) and with the likes of

Johnny Farnham (then a chart-topper with Sadie the Cleaning Lady and whom they got into soccer), the Yardbirds (then featuring the little known Jimmy

Page playing guitar with a violin bow) and Tom Jones . . . who was so impressed by them he brought beer

backstage and sat with them until he got called to do his set.

“Someone like that being just one of the boys, those are things you never forget.”

Nor does he forget sharing bourbon'Coke in a hotel pool with the boozy Burdon.

There was a camaraderie between bands, although Stott says of Page “I'd love a dollar for every time I've said, or other guys in the band have said, 'If only I stood with him and taken a photo' “.

When some overseas solo acts toured the band would back them.

“I think what promoters like Harry Miller hooked onto was he was getting pretty good value because Larry's Rebels were scoring chart songs and could open the show, then Larry would take off and the four of us could stay onstage and back people like British hit-makers Paul and Barry Ryan or Australian Johnny Farnham."

Paul and Barry Ryan however had orchestrated songs so the group asked them to send out charts and singles to study.

“I was never taught to read music, no one in the band could read really, but through sitting down with the charts and working out where the stops and beginnings were you could actually pick up what was being played.

“I can remember at 15 or 16 I went to this rehearsal with Paul and Barry Ryan – and we'd already rehearsed the stuff through – and they were totally happy with it. The fact we could do that impressed them.

“I had my music stand there with the music on it which . . . was quite decorative, because I never looked at it once. But they didn't know that.”

There were numerous tours with international stars and Stott says Page was quiet and just wanted to play guitar.

“We had the news that Jeff Beck wouldn't be coming out with the Yardbirds and so it was all doom and gloom, and someone said this new guitarist called Jimmy Page would be on the show. But that would have been one of the best tours of the lot.

“We'd get on a bus and Jimmy Page would say to John Williams, 'Hey Willie, where's your guitar?' and the two of them would sit in the back of the bus playing together. He was such a humble character and John would say, 'How did you do that?” and Jimmy would show him. Or Jimmy would say, 'What did you do there?'

“They made us feel quite equal and we

were having fun. We'd have a fart chart up on the bus and I sometimes

wonder what they thought they had run into when they came down under.

“They made us feel quite equal and we

were having fun. We'd have a fart chart up on the bus and I sometimes

wonder what they thought they had run into when they came down under.

“Everybody used to learn off everybody else and you'd be talking with someone about how they recorded n the UK with a kick drum, and you'd get in to the studio so you could try it in that way, and you passed that information on to somebody else.

“One thing that has become clear to me – and I've got back into music lately and when I am out and about I'm delighted by this – it's that if you are a muso you are a mate.

“Back in the early days we all stared off like that ,but unfortunately what happened was the competition started, particularly with the promoters. You had the Shiralee and the Beatle Inn and Zodiac Records on the one side and on the other would be Phil Warren and the Platterack and the Monaco.

“We worked in all those venues but over time what happened was the La De Das and us would release records and then people would go into the radio DJs – and our managers were into this too – and say, 'Let's have a competition and see which gets the most votes'.

“So over time people talked to us about the La De Das as if they were our enemies, and we weren't. We were all good mates . . . but there was that undertone of trying to divide you into sides.

“I'm so pleased in the industry now that doesn't seem to be the case, at least not where I'm playing these days.”

Sometimes the pleasure couldn't compensate for the fact they band wasn't making as much money as outsiders might have thought. By the time they were in Australia towards the end they were having to be very cautious every week when payday rolled around, paying off HP, rents and bills first before diving up the remainder.

“There was a short period of time when we were living off boiled rice and tomatoes because tomatoes were really cheap. And tinned peaches were cheap too. So in the morning you'd have boiled rice with peaches and for lunch you'd have cold tomatoes and rice and for dinner it was hot tomatoes and rice.

“That was it, you had to wait until you got paid the next time.”

Stott says the end of Larry's Rebels was almost inevitable.

“We were getting good work but we were starting to stagnate, 10 gigs a week or maybe less than that . . . I suppose because we'd had such a rapid change over three or four years – it was exciting, everything was new, we never knew where we were going to be next week – and all of a sudden things started to become very mundane.

“I personally could see at some stage that unless we went to the UK or there were changes of personnel we would definitely stagnate. I was sensing Larry was thinking the same thing.”

But going to Britain was a huge step into a more difficult market: “Australia's Twilights had just come back from the UK and had tried to break in and just couldn't, we'd toured in Australia with the Easybeats who told us how hard things were over there for them, Max Merritt had gone over and was virtually playing for nothing just to break in.”

“There was doubt then, whereas there had never been doubt before."

This was when the band started to divide off, some wanted to give it a shot, others thought it better to just to make some decent money where they were. In '68 Terry Rouse quit feeling that being broke wasn't much compensation and that at 21 he was getting a bit past it. Mal Logan was brought in on keyboards.

“So Larry went his way -- personally I accepted that and I think the band did too. He could go off and be a solo act and do songs that weren't commercially suitable for Larry's Rebels and show his voice off . . . but we didn't know what we were going to do.

“We used to go down to the 1480

Village in Auckland and Jigsaw used to play down there with Glyn

Mason singing, and I loved his voice. I'd always been a Traffic fan

and they did quite a few Traffic songs . . . so I said to the guys

they should come down and listen to him, and they fell in love with

him.

“We used to go down to the 1480

Village in Auckland and Jigsaw used to play down there with Glyn

Mason singing, and I loved his voice. I'd always been a Traffic fan

and they did quite a few Traffic songs . . . so I said to the guys

they should come down and listen to him, and they fell in love with

him.

"We put a proposal to him and it took him around 12 hours to come back and be totally committed.

“When we went back to Australia in '69 we decided we wanted a Hammond and Leslie unit – we are talking about $10,000 on those days – and Mal said there was no way he could afford it. The band suggested we get it on HP and pay it off first when we picked up our money and further down the track once it was paid off Mal could pay the boys back and it becomes your equipment.

“We never got the money back of course," he laughs, "as you didn't in those days.

“So we were committing ourselves to situations unbeknowingly, because we were seeking a new fat sound . . . so in Australia we played for about 18 months . . . but after a short period of time I remember thinking I wasn't happy and I spoke to Viv [McCarthy who had replaced bassist Leekie just before fame beckoned] and he felt the same . . . and in the space of about two or three days we called a meeting.”

It was over and they went their separate ways – Mal became the keyboard player with the Little River Band – and Stott came home. Broke.

“You know, you dedicate yourself to the music so all your decisions are based around your ability to play and the buzz you get out of playing.”

But in the music world there are so many sad stories, he says.

On the advice of his brother he got a job at Schweppes, they amalgamated with Innes Tartan and later combined with Coca-Cola to create Oasis Industries and Stott rose to be sales and marketing manager . . . then was head-hunted by Villa Maria Wines.

“I don't regret anything that

happened at that time [when the band split]. My mum and dad were

supportive even when I got home and I said to my mum I thought I

might have to sell my drums.

“I don't regret anything that

happened at that time [when the band split]. My mum and dad were

supportive even when I got home and I said to my mum I thought I

might have to sell my drums.

“She wouldn't let me sell anything I had of the band, and she was quite wise. I gig now and I'm still using the same kit I was using in '65 and '66, I've just refurbished it.

“But when I came home at age 21 I realised I was thinking about where I was going in my life.

“If I met up with a lady I really fancied I couldn't afford to take her out for dinner let alone marry her. I had to get a bit of stability.

“I actually came home with a lady from Australia and we stayed at my mum and dad's – the things in my bedroom were in the same position as when I left, they anticipated I'd be back at some stage.”

And so the young man who had been born and raised in a greengrocers shop as much as on rock'n'roll stages just got a day job . . . and enjoyed it.

“I liked the idea of starting work at 7.30 in the morning, although that only lasted a few years.

“I now look at people who have always been musos – and I say this in the nicest way because in a certain way I feel sorry for them – but there are a lot of other things to life besides music . . . which fortunately I've been able to experience.”

post a comment