Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Joy Division: The Sound of Music

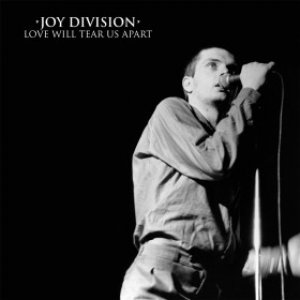

Many decades ago on his Graceland album, Paul Simon sang, “Every generation throws a hero up the pop charts”. New Zealand threw one of the most unexpected up its singles chart: At the dawn of the 80s Joy Division's Love Will Tear Us Apart went to number one.

Some might think that confirms the country as emotionally bleak, a place where novels and films almost invariably involve the murder of a child in a small town, and black is the most common colour in wardrobes.

There's a less dramatic explanation: The song wasn't available for a long time and when it came out everyone who'd read NME or heard it on a knocked-off cassette from a mate in London – as I did – rushed out to buy it.

By most measures, Joy Division out of Salford in Manchester in the late 70s were a rare band. In the hands of producer Martin Hannett their spare and cavernous sound was somewhere between post-punk and (whisper this low) ever-present disco with the emphasis on Stephen Morris' powerful but simple beat, the huge bass of Peter Hook mixed high like a lead guitar, and the swirling melodic keyboards of Bernard Sumner.

And out front was singer and lyricist

Ian Curtis who would commit suicide on May 18, 1980 . . . just

before the band was to leave for their first American tour.

And out front was singer and lyricist

Ian Curtis who would commit suicide on May 18, 1980 . . . just

before the band was to leave for their first American tour.

An early death is a big deal in rock culture. Like some prehistoric insect embalmed in amber, the dead never age. Unlike the rest of us – Can you picture Jim Morrison today at 72, Hendrix a year older and Elvis at 80? -- they remain forever young, beautiful and full of promise.

Today Curtis would be almost 60 if he'd lived, but when you listen to his lyrics – and factor in mental instability and epilepsy – he was never going to make old bones.

A poetic spirit impelled him, so comparisons with the suicided Sylvia Plath (dead at 30, face down in the gas oven) and the like are not far from the mark.

But in rock culture what made Curtis unique was he, like Morrison, sang in a baritone which conveyed an emotional weight never available to the likes of Michael Jackson or Prince.

He sounded serious. And he was.

Ironically then, his bandmates – by their own admission just good Manc lads at the time – didn't quite realise what was going on inside Curtis' disturbed head until after he died and only then did they look at his lyrics: Few colours other than grey; images are of isolation and endings; questions throughout (“Where will it end,” in Day of the Lords, “Why is the bedroom so cold” on Love Will Tear Us Apart are typical) and everywhere there was introspection and bleakness.

No surprise then that the first version of Joy Division was called Warsaw, after the Bowie piece Warsawa on his Low album. An interesting if cheerless reference point to start a career in popular music?

Perhaps because Curtis dealt with universal themes of emotional distance and self-doubt – as well as the music being not time-locked as overtly “post-punk” – Joy Division will always find a new audience. Every generation, to paraphrase Paul Simon, will discover them anew and – in the music and words -- hear something which speaks to it.

Joy Division's time has come again.

There is the reissue of their two Hannett-produced albums Unknown

Pleasures and Closer (on

vinyl); their essential Still collection of unreleased studio

material and the live recording of their final show at Birmingham

University a fortnight before Curtis' suicide (double vinyl); and the

Substance collection of B-sides and such on CD and double

vinyl.

There is the reissue of their two Hannett-produced albums Unknown

Pleasures and Closer (on

vinyl); their essential Still collection of unreleased studio

material and the live recording of their final show at Birmingham

University a fortnight before Curtis' suicide (double vinyl); and the

Substance collection of B-sides and such on CD and double

vinyl.

Even now that final concert on Still is hard to listen to, knowing what we now know: On Disorder he screams, “I've got the spirit, but lose the feeling feeling feeling feeling”. That final “feeling” sounding like a note of defeat defeat defeat defeat.

And with “dance, dance, dance to the radio” on the thrilling Transmission, the last time he would ever sing it, we can hear it isn't about dance, but desperation.

“And we would go on as though nothing

was wrong,” he sings, “and hide from these days we remained all

alone. Staying in the same place, just staying out the time. Touching

from a distance, further all the time. Dance, dance . . .”

“And we would go on as though nothing

was wrong,” he sings, “and hide from these days we remained all

alone. Staying in the same place, just staying out the time. Touching

from a distance, further all the time. Dance, dance . . .”

That's poetry.

But as he screams over and over “dance, dance, dance to the radio” you know this is not the dance of life.

It's the dance of that ever-present other.

And he knew it.

MickJ - Dec 21, 2015

Brilliant article Graham.

Savepost a comment