Graham Reid | | 9 min read

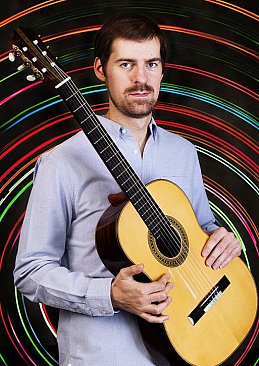

Nada-Anada: Joy. Simon Thacker and the Nava Rasa Ensemble

When Simon Thacker was growing up outside a small village some distance from Edinburgh in Scotland, the rest of the world seemed a very long way away.

But as an aspiring guitarist he connected to it through music by exploring the blues, classical music, folk and more.

He found his way to Indian and Spanish music and so these days the world doesn't so much come to him but – with various ensembles – he takes his music to it.

In the past six months or so he's played in Pakistan and India (with tabla player Sarvar Sabri in Pakistan) and soon brings comes to New Zealand for a short national tour (see dates below) with his Ritmata ensemble.

“Simon Thacker's Ritmata is my more

jazz influenced group,” he laughs. “It's the highest octane, most

souped-up of my ensembles in that it has drums, double bass, piano

and guitar. The music comes with influences from all round the world

and the different experiences I've had from diverse cultures.”

“Simon Thacker's Ritmata is my more

jazz influenced group,” he laughs. “It's the highest octane, most

souped-up of my ensembles in that it has drums, double bass, piano

and guitar. The music comes with influences from all round the world

and the different experiences I've had from diverse cultures.”

Thacker – whose excellent Rakshasa album with his acclaimed Svara-Kanti group was featured at Elsewhere and who answered our Famous Elsewhere Questionnaire on the strength of it – is, aside from being a touring and recording musician, classical guitar tutor at Edinburgh Napier University and Edinburgh College.

But he thinks deeply when I ask him about classical music background.

“Classical music gave me the education, knowledge, technical means and experience to then further explore whatever I wanted to. It also, I suppose, gave me a tradition (not coming from a musical background), or at least the notion of belonging to a tradition, from which I could develop, add to, ignore, rail against or react to.

“Classical music is such a wide term, especially with regard to classical guitar, that its meaningless in any real sense, and annihilating all those superficial barriers of what constitutes a 'genre' is something I think my work does increasingly readily.

“I've immersed myself in so many 'traditions', 'genres' and 'cultures' that aspects of them all seep into your subconscious and in the end it just come out as music, a means to expression.”

He has been nominated for a Royal Philharmonic Society Music Award, was a winner of the 50th Park Lane Group Awards (resulting in his highly commended solo London Purcell Room debut) and has performed as soloist with many orchestras, including the RSNO.

As he prepares for appearances at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival (with Svara-Kanti and singer Raju Das Baul) he's also looking forward t the New Zealand tour.

“We are looking forward to coming because no matter what the weather we'll be in shorts and t-shirts showing off our milk-bottle white complexions.”

How did you get to this point where you embrace all these styles of music. In your childhood were you surrounded by all of this?

No, the opposite if anything. I was brought in a very rural area just outside Edinburgh and I still live in the same area, about two and half miles outside the nearest town.

I was brought up as an only child in the country so took up music at the age of 10. But even before that I was obsessed by collecting CDs and LPs and listening to all different styles. At high school I particularly got into world music, it was an exploration.

My first obsession of non-mainstream music was pre-war blues: Son House, Skip James, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Willie McTell and so on. Through that I explored African music, then I studied classical music and got into flamenco, then I started to follow the gypsies' path from Rajasthan down the Silk Road.

I was seeing the connections of music across the world and basically educating myself.

Is this because being an only child in a remote area you didn't have playmates and this became a preoccupation?

Probably. I was a loner, not so much now. So it was escapism and the imagination running wild. There was something about music which just grabbed me and that was my porthole to different worlds. I lived in beautiful area surrounded by horses, sheep and cattle and hills, but I can't put my finger on why music was important to me. It was, even before I took it up properly.

I was trying to explain to some students the other day the young Rolling Stones infatuation with the blues and said they had to imagine if they were living in London in the early Sixties songs about, “Mama cookin' chicken fried in bacon grease” would seem strangely exotic and somewhat mysterious. Let alone voodoo references.

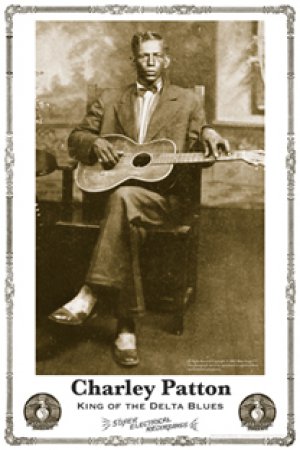

Oh, yes. Exactly. In primary school I

was into heavy metal like Megadeth, and AC/DC was an early favourite.

That got me into the blues by late primary school so by the time

people were listening to Nirvana or whatever I was listening to

Charlie Patton. It was like a time-traveling device into another

universe.

Oh, yes. Exactly. In primary school I

was into heavy metal like Megadeth, and AC/DC was an early favourite.

That got me into the blues by late primary school so by the time

people were listening to Nirvana or whatever I was listening to

Charlie Patton. It was like a time-traveling device into another

universe.

There was a romanticism about it. There was a different language to it and by, say, 18 when I was studying classical playing I was throwing my guitar in the air at the end of a piece . . . because I'd read about Charlie Patton doing that in the juke joints where you had to grab the attention of people.

I don't do that any more because of the price of my guitar now, you learn the value of these things.

But that music transports you and your imagination fills things in.

If Charlie Patton had recorded in a pristine studio and there were videos on You Tube of him playing then maybe that mystique wouldn't be there so much. Your mind fills things in.

People certainly filled in Robert Johnson's story.

Exactly. It became probably a lot more exciting than it actually was. People's imagination about that makes it more visceral. I remember reading about Robert Johnson and apart from those few songs he recorded he used to play really the most cheesy of cheesy pop songs at functions.

When you got into classical guitar did you find the same degree of exoticism? That you could put yourself back into what these composers were like two or three centuries ago.

No, not quite. That was at late high school maybe, but before that I felt a closeness to Western classical music in that it was part of my culture, therefore it didn't have quite such a mystique. It's difficult to explain actually and I'd not really thought about that before.

The Spanish and Latin American repertoire being so important. Classical composers like Leo Brouwer took influences from Afro-Cuban music and mixed it with influences from Stravinsky or whatever.

To convincingly convey that music you had to do your homework more so than say if I'd played the piano . . . like playing Chopin, Mozart and Beethoven.

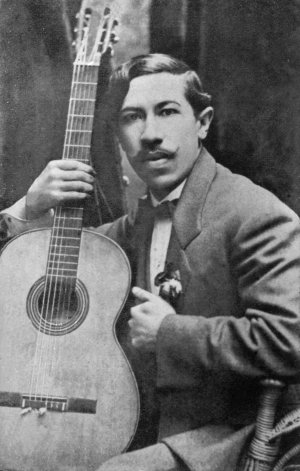

For example Barrios Mangore the great

Paraguayan guitarist, was like the first world musician because he

was taking folk music Paraguayan style and marrying it with

Chopinistic harmony and Bach. So you have to know both things to play

that music.

For example Barrios Mangore the great

Paraguayan guitarist, was like the first world musician because he

was taking folk music Paraguayan style and marrying it with

Chopinistic harmony and Bach. So you have to know both things to play

that music.

It was almost like I saw classical music as a construct. If you are playing Bach it is a very difficult world to get into, it is as alien almost as India because of the time distance . . . but because it's Central European it has a different sort of appeal.

What [Western] composers were using to construct the music isn't so weird or fantastic in that way.

That appeals to a different part of

your intellect or sensibility then?

Maybe. With Indian music I

could tell straight away, even though I couldn't totally understand

it, that the raw material was being used in a totally different way.

Upside down from Western music. There's no harmony, there all these

ragas in different scales, a systemised rhythmic system which is

incredibly exciting although I didn't understand what it was . . .

But in Bach, he was using harmonies that I could understand. A lot of pop songs are based on the same sort of harmonies, albeit in a different way.

The classical musical material was therefore based on something I knew, whereas the Indian material was completely different., the rhythm, pitch and harmony wasn't there.

How did you school yourself in Indian music? Did you take lessons?

No. Most of my life I'd listened to Indian music so on an intuitive level I'd developed an understanding, even if it was more of a spiritual and emotional understanding rather than a technical one.

Then I just started to read, watch and ask. I got books and instructional DVDs of the rhythmic language of South India. So I got the raw material to gain that knowledge in conjunction with listening obsessively.

At some point you must have hooked up with some Indian musicians and asked if you could have a go . . . with some trepidation I guess.

What happened, and looking back it was totally by chance, the first project was the Nava Rasa Ensemble, a nine-piece ensemble. There was indian violin and tabla, a string quartet, guitar, double bass and percussion.

I commissioned two composers, one was Nigel Orborne from Scotland and one was Shirish Korde who is based in Boston, he's one of the very few Indian composers who has brought his voice into the Western contemporary classical world.

That was like a contemporary Indian academy almost in that I could observe those pieces and be at the start of their creation and bring them to life and work with them forcefully, then record and tour them.

I could see what aspects I wanted to explore more and at that time I didn't compose quite so much. I hadn't composed anything Indian and was very much finding my voice compositionally, but I saw what worked well and what wasn't so successful. I could see what areas of Indian music I could really take on because they spoke to me on an emotional level.

But then with Svara-Kanti, which was a

much more interactive and forcefully experimental, I could bring

improvisation into it, and that was where I could explore all those

things which had been coalescing in my mind.

But then with Svara-Kanti, which was a

much more interactive and forcefully experimental, I could bring

improvisation into it, and that was where I could explore all those

things which had been coalescing in my mind.

You've had a number of different ensembles and most recently you went to Pakistan.

Yeah, I always got a number of things on the go. Last November I toured India with Svara-Kanti, the Indian debut of the group which initiated a new collaboration with Raju Das Baul from the Baul folk singers.

In January in Pakistan it was myself with Sarvar Sabri, the tabla player, and showcasing the music in Pakistan.

And how was these received there, because in a sense you are taking their music back to them?

Not really, because I'm not trying to play Indian music. I'm not trying to play fusion. I see it as my creation of new traditions. I see fusion as watering it down, people from different traditions meeting in the middle where you take out the complicated part, so it's, “You play your tradition and I'll play mine and we'll meet in the middle”.

In my way I immerse myself in their tradition and, “You should do the same in mine and we'll meet on the extremities . . . and take it somewhere it's never been before”.

So in India we got standing ovations and great reviews and it went as well as I could have imagined, and we showed lots of different facets: there were Punjabi songs, songs of mine, there was the new collaboration with Raju Das Baul, I even played a Gaelic song which I'd re-imagined with cello.

In Pakistan the people loved even the Gaelic song which has some resonance.When I was playing in South India they didn't know Punjabi music much, so I was bringing to that area something they didn't know.

So I was taking music which was less

grounded in tradition and more experimental in many ways. But they

really appreciated that I could understand music from that part of

the world and that I was doing something that had not been done

before. That gets a response because they appreciate how I'd immersed

myself in it, but also that I'd taken it somewhere else.

So I was taking music which was less

grounded in tradition and more experimental in many ways. But they

really appreciated that I could understand music from that part of

the world and that I was doing something that had not been done

before. That gets a response because they appreciate how I'd immersed

myself in it, but also that I'd taken it somewhere else.

So they are hearing this as something new rather than something borrowed.

It's interesting you asked if I'd had lessons. Quite often people ask if I'd ever played sitar but I have no interest in ever doing so because I would just be setting myself up for a massive fall. If I start to pay sitar I'm never going to be as good Vilayat Khan or Enayat Khan or any of the great legends. I'm always going to be a second-rate sitar player.

Classical guitar isn't a natural Indian instrument. If you listen to sarods or veena or sarangi, they have a metallic and strident sound with overtones from sympathetic strings.

Classical guitar is basically from a late 19th century Western romantic aesthetic which is very rich tonally and has a very beautiful sound. So because it doesn't sit in that [Indian] world, that makes me explore the instrument even more and find solutions to what it is I'm trying to express, asking, “What are the things I want to make part of my musical language from different traditions?”

I want to find ways to realise that and that makes me look to new musical and technical possibilities.

That's the impetus.

SIMON THACKER'S RITMATA ENSEMBLE NZ TOUR

30 Aug 3pm, Taranaki International Arts Festival, Famous Spiegelten

1 Sep 8pm (doors 7pm), Wellington, Meow, 9 Edward St, Te Aro, Wellington

3 Sep 7pm, Christchurch Arts Festival, TVNZ Festival Club

4 Sep 8pm (doors 7pm), Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology, Nelson (also afternoon workshop)

5 Sep Le Cafe, Picton, 12-14 London Quay

6 Sep 8pm (doors 7pm), Masterton, King St Live, 21 King Street

8 Sept: Workshop 4-6pm, Studio 318, KMC Building, Shortland St, Auckland

9 Sep 1pm, University of Waikato, 1 Knighton Road, Hamilton

9 Sep 8pm, Auckland, Creative Jazz Club Aotearoa

post a comment