Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Queen: I Want It All

Some years ago a friend of mine worked for a major international record company. At the time we had lunch in an early November, with the downturn in CD sales and the constantly shifting ground of the internet, things were getting tougher.

So as the second bottle arrived only just in time we were talking about this situation in somewhat glum terms.

But, I said cheerily, at least they had a license to print money in the run-up to Christmas.

He looked at me puzzled.

I said, “Queen”.

Even he laughed at that. And it was true.

In their Freddie Mercury-lifetime Queen released 14 studio albums (the posthumous studio construction Made in Heaven was released four years after Mercury's death in November 91). But during that time and since they've released the same number of compilations, many of them in October and November.

And of course box sets, live albums and DVDs.

Even as late as November last year a “new” Queen album appeared, Queen Rocks, which mostly picked up material recorded in the 80s with Mercury's vocals put in new settings by the remaining band members and producer William Orbit.

There's no shortage of Queen in the world, but here they come again, this time on remastered 180gm vinyl pressings. All their studio albums (and Made in Heaven) beautifully re-presented in a massive box or available individually.

For those of the CD or download generations just getting in to vinyl, this is a formidable catalogue, so let's trip lightly through it because Queen were often a great deal of melodramatic fun.

Few would dare even

try something as silly and ambitious as Bohemian Rhapsody, let alone

follow it up with retro-rock singles (You're My Best Friend, Tie Your

Mother Down). Or release a song entitled Fat Bottomed Girls (unless

you were Spinal Tap, and sometimes they were that too, gloriously

full of self-parody).

Few would dare even

try something as silly and ambitious as Bohemian Rhapsody, let alone

follow it up with retro-rock singles (You're My Best Friend, Tie Your

Mother Down). Or release a song entitled Fat Bottomed Girls (unless

you were Spinal Tap, and sometimes they were that too, gloriously

full of self-parody).

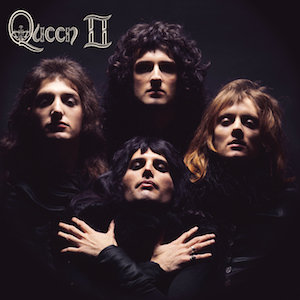

Queen's first two albums of the early Seventies (Queen I in a cover which has Mercury in the spotlight, and Queen II in their only iconic album cover, shot by Mick Rock) are very much influenced by fey if hefty prog-rock so are best not returned too if you really like where they went after that.

However it's worth noting that even at this early stage how complete their vision and self-image was.

As their first

London publicist Tony Brainsby noted: “When they came in

originally, they knew exactly how they wanted to look and how they

should be portrayed for the press.

As their first

London publicist Tony Brainsby noted: “When they came in

originally, they knew exactly how they wanted to look and how they

should be portrayed for the press.

“They knew who they were and what they were, which was rare for a rock group, believe me. It is was just another reason why you knew they were going to make it.

“They had already designed their coat-of-arms logo. The clothes, the colour schemes, it was all there.

"You didn't have to get people in to style them.”

Very quickly Mercury persuaded Brainsby that they should get in fashion designer Zandra Rhodes to make their touring costumes.

Queen were on their

way image-wise and although in retrospect those first two albums

sound very much locked in their period they had already made an

impression. Sounds magazine billed them as “Britain's Biggest

Unknowns” in early '73, and the country's third best newcomers.

Queen were on their

way image-wise and although in retrospect those first two albums

sound very much locked in their period they had already made an

impression. Sounds magazine billed them as “Britain's Biggest

Unknowns” in early '73, and the country's third best newcomers.

The Sheer Heart Attack album ('74) is where they start to get interesting for mainstream listeners, the album included the hit Killer Queen (which won them their first Ivor Novello songwriting award in Britain and a Golden Lion in Belgium).

But more significantly it marked a move into more concise (again, if hefty) pop-rock.

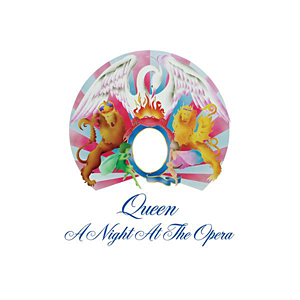

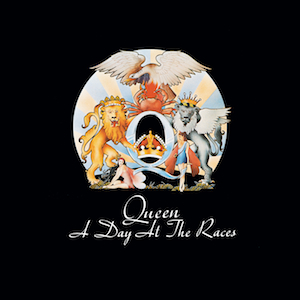

A Night at the

Opera ('75) and A Day at the Races ('76) — both named after Marx

Brothers films — is where the story really begins; the former

includes Bohemian Rhapsody and You're My Best Friend, the latter Tie

Your Mother Down and Somebody to Love.

A Night at the

Opera ('75) and A Day at the Races ('76) — both named after Marx

Brothers films — is where the story really begins; the former

includes Bohemian Rhapsody and You're My Best Friend, the latter Tie

Your Mother Down and Somebody to Love.

That Marx Brothers reference is important because after their earnest start Mercury stopped taking himself quite so seriously and their albums became manifestations of his flamboyancy, melodrama and excesses.

Freddie was having fun with his fame.

“Boredom is the biggest disease in the world,” he said. “Sometimes I think there must be more to life than rushing around the world like a mad thing . . . but I'm an entertainer. It's in the blood . . . I am just a trouper, dear. Give me a stage.”

Bohemian Rhapsody

even today — perhaps more so in these cautiously careerist times —

is a weird song, “an absolute lunatic asylum of a song” according

to influential British radio jock Tommy Vance.

Bohemian Rhapsody

even today — perhaps more so in these cautiously careerist times —

is a weird song, “an absolute lunatic asylum of a song” according

to influential British radio jock Tommy Vance.

“Most people at Radio One immediately dismissed it as a complete disaster but — surprise, surprise — they played it. And what was so brilliant about it was that it gave everyone a chance to shine and express themselves; it gave the rock cult DJs an opportunity to play something that was not obvious, and to use their imagination; it gave everyone who was involved in avant-garde radio the chance to make a statement and a name for himself.

“It gave the public an excuse to rise to the occasion.

“I remember thinking the most predominant thing about the record was that it was so magnificently obscure it just had to make it.

“It's all over the place . . . and if you try to dissect the lyrics the song is utterly meaningless. It is about nothing. It is just a string of dreams, flashbacks, fast-forwards, vignettes, completely disjointed ideas . . . but the intent was remarkable . . . it is brilliant.”

In October '77 it was voted the best British single recorded in the previous 25 years by the British Phonographic Industry.

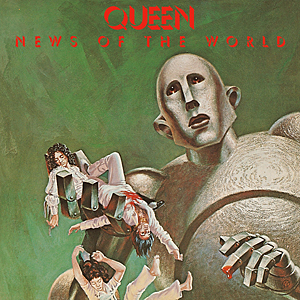

By this time Queen

were commanding huge stages and so the follow-up album News of the

World ('77) reflected that in their two stadium-sized crowd-pleasers

We Will Rock You and We Are the Champions, both of which were reviled

the Britain's punk-obsessed music press at the time.

By this time Queen

were commanding huge stages and so the follow-up album News of the

World ('77) reflected that in their two stadium-sized crowd-pleasers

We Will Rock You and We Are the Champions, both of which were reviled

the Britain's punk-obsessed music press at the time.

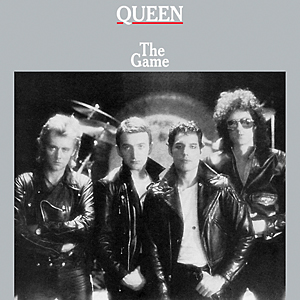

The patchy Jazz ('78) is the least loved album in Queen's mature career but they returned to form (and the singles charts) with The Game ('80) and the hits Another One Bites the Dust written by bassist John Deacon, and Crazy Little Thing Called Love which proved --as if any further evidence were necessary -- that this was an enormously talented band of individuals, and not just Freddie and some anonymous friends.

Flash Gordon ('80)

was the soundtrack to the film of the same name and is mostly

instrumentals, so not for the casual Queen listener. Nor is Hot Space

(notable for the duet with Bowie on Under Pressure but not much

else).

Flash Gordon ('80)

was the soundtrack to the film of the same name and is mostly

instrumentals, so not for the casual Queen listener. Nor is Hot Space

(notable for the duet with Bowie on Under Pressure but not much

else).

From there on through The Works ('84, with I Want to Break Free, and Radio Gaga written by drummer Roger Taylor), A Kind of Magic (86) and The Miracle (89) they sounded like a good band in a holding pattern.

But still the show went on.

“Freddie was the

world's greatest frontman,” said Tony Hadley of Spandau Ballet.

“Freddie was the

world's greatest frontman,” said Tony Hadley of Spandau Ballet.

“Plus, Queen records made you feel good. There was always this underlying sense of fun.”

But the party was coming to an end, and Mercury knew it.

One of the songs on his '85 solo album Mr Bad Guy was Living on My Own, of it he said, “[It] is very me.”

The gloss had come off.

In August '86 Queen played at Knebworth Park before at least 120,000, perhaps as many as 200,000. Afterwards Mercury, for so long the party man, went away quietly. It was to be his final concert.

He was in the early

stages of the rapidly advancing Aids-related illnesses which would

kill him and the last Queen album in his lifetime was the uneventful

Innuendo (released in early 91, nine months before his death).

He was in the early

stages of the rapidly advancing Aids-related illnesses which would

kill him and the last Queen album in his lifetime was the uneventful

Innuendo (released in early 91, nine months before his death).

The final song on the album, written largely by Brian May is . . . The Show Must Go On.

And, when it came to Queen reissues and repackaging, it most certainly did.

Still is . . .

There's been the stage show, the tours with Adam Lambert, and much more.

The talk about a Freddie bio-flick hasn't gone away either . . .

Good band, great songs. But really, must the show go on this long?

.

.

.

post a comment