Graham Reid | | 8 min read

The Dave Rawlings Machine: Candy

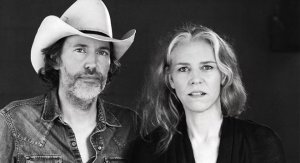

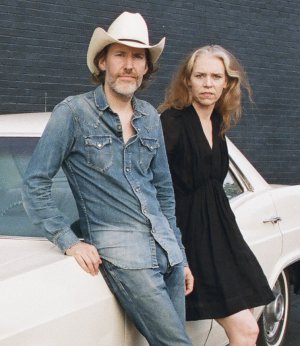

It has been almost five years since Gillian Welch's Grammy-nominated album The Harrow and the Harvest, and over a decade since she and longtime partner Dave Rawlings appeared in New Zealand.

They will correct the latter oversight when they play the Civic in Auckland on January 28, but in conversation Welch says there's no new album forthcoming under her own name.

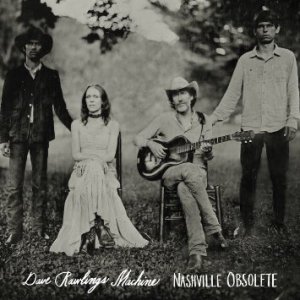

No matter, because the pair have another outlet for their songs as the Dave Rawlings Machine (which has them working with other players and Rawlings-fronted songs to the fore). The second album from that source Nashville Obsolete – named for their adopted hometown where they own the handsome studio where Young recorded Comes A Time – is what they are currently touring.

Elsewhere has spoken with Welch previously so there's no need to readdress how she and Rawlings have been making acclaimed, award-nominated albums these past two decades which are a contemporary extension of traditional American genres such as folk, blues, country, bluegrass and even hints of early rock'n'roll.

But while their audience has grown in line with the plaudits and decent, if never spectacular album sales, she freely concedes their songs can be demanding: The music can be spare and measured, the stories dark, the characters within them troubled, tortured or struggling.

Uneasy listening we might say, but Welch is in good humor when the phonecall catches her.

The first thing we hear is the GPS . . .

Hello Gillian, where am I talking to you at?

I'm on the road because I'm driving and am between, coming from Austin and I'm driving to Albuquerque in New Mexico and am through Abilene headed for Lubbock right now, probably have dinner in Lubbock. So that's where I am, I'm goin' by some cotton fields right now.

I know that drive and stayed in Lubbock to visit Buddy Holly's grave.

Oh yeah, gotta do that.

First of all congratulations, both

of you got a Lifetime Songwriting Achievement Award from the

Americana Music Association in Nashville just before Christmas.

First of all congratulations, both

of you got a Lifetime Songwriting Achievement Award from the

Americana Music Association in Nashville just before Christmas.

We did, it was very flattering and a nice surprise. I think we were too young to get a lifetime achievement award. One of my friends joked and called it our Mid-lifetime Achievement Award . . . but we took it seriously and it was an honour to get it with the other people being honoured [among them Lucinda Williams, Shakey Graves, and Los Lobos].

We interpreted it as how nice it was in a 20 year career that people like our body of work and value the songs, I'm gonna take it as “keep up the good work”.

Dave was joking, “Does that mean they want us to stop?”

I imagine it is especially gratifying to be accepted as an original songwriter who is part of, but also extending, a tradition into the 21st century.

Definitely. It means a lot to us when our work gets recognised by the songwriting world because in essence that is what we are, first and foremost we are songwriters. If it weren't for our original songs I don't think we'd have a career. No one paid much attention to me when I was singing other people's songs, or folk songs, which is really what I came up doing.

Much as I love them, it wasn't until I started writing my own songs that the world took any notice.

And of course it always meant a lot to us also that even with writing new and contemporary songs that some of the most passionate support we got came from musicians from the traditional world, old time musicians, bluegrass musicians, mountain musicians . . .

They were the first community to immediate see what we were doing and see we taking the tradition and making it our own and moving forward. I feel like I've been lucky to have the support from the musicians.

I guess that's what they mean when they call you “a musician's musician”.

That's another way of saying, “and there's no money in it”.

[Laughs] It does mean that too, it's not pop. But I'll take it because there's a wonderful feeling when you feel like you are understood. It's great to feel that what you are putting into it is being received. I'll take acclaim from a room full of musicians anytime.

I know this is going way, way back but I want to talk with you about songwriting because you actually studied it as a craft at Berklee. What were the valuable lessons did you take away from that?

I learned you should never ever give in to cliché, stay away from cliché unless you are doing it knowingly and for a reason. That's the worst kind of laziness and it's going to hurt you in the end. Cliches go by and that's when people to tune out, and you never want a listener to tune out. You want them to stay right with you line-by-line, word-by-word. You gotta try never to lose them.

So I learned that, and also had it drilled into my head – and I don't know if I ever got there – but I certainly did come to believe in the early days of working on songcraft is that you have to keep your eye on all fronts.

You can't slack off anywhere, so your idea actually has to have something in it, and your poetry – which will relate to your song title if you are doing good work -- has to connect to the idea.

And your song form has to be there too.

Also if you are going to be a performer as well as a writer it has to be something you sound good doing. It has to be a song that suits you

That's a lot to manage but to be successful, you have got to do that.

And I say that as someone who doesn't

manager that all the time. I have songs and some are stronger in some

areas than others. Dave and I will put a song out there if we feel it

has something. There aren't too many we feel are completely

successful, but they have something we feel is worth putting out

there.

And I say that as someone who doesn't

manager that all the time. I have songs and some are stronger in some

areas than others. Dave and I will put a song out there if we feel it

has something. There aren't too many we feel are completely

successful, but they have something we feel is worth putting out

there.

I've read that before The Harrow and the Harvest you were unhappy with your writing. You are good self-editors obviously, what was the source of that dissatisfaction?

It's kinda tricky because if you do this for a while – and I have been at it for a while – you want your next record to show your progress forward, which means change. But it has to be the right kind of change.

It's a pitfall that writers and performers struggle with, as you build a body of work, how do you stay true to it, but also evolve?

I think what happened to me was I was perhaps trying to push forward and try new things – which you have to do – but I wasn't satisfied with the direction I was moving in.

We gave it a go but can't put in to words what direction that was, but I just know that in the end Dave and I didn't dig it. So we scrapped everything we'd been doing and said, “Okay maybe not these songs”, and there were maybe two notebooks full – we still work in pencil and paper – we each have a couple of notebooks going.

We just set all those aside and just started again.

What cracked it open was writing and recording the first Dave Rawlings Machine record [A Friend of Friend in '09].

I guess for you personally the

Machine allows you more of breathing space because Dave fronts more

of those songs?

I guess for you personally the

Machine allows you more of breathing space because Dave fronts more

of those songs?

It does, but it doesn't take any weight off me as a songwriter because we still write them the same way as we do for a Gillian Welch record, but it definitely gives us more breadth, which is what we are looking for.

Because any time we put out a record under my name it's what we call a duet record, it's pretty intense and focused. It's like life on a spaceship, just the two of us.

Your concert here is billed as An Evening With Gillian Welch, so it is just the two of you.

Yes.

Are you recording again under your own name now?

Not yet, we're really touring this new Machine record Nashville Obsolete and are about three-quarters the way through this tour, we've travelled about 12,000 miles so it's been a hefty tour. I've really been enjoying it because we have been out with all the musicians who made the record.

I want to ask you about that ever-growing audience you have built up over a long period now, your music is quite demanding because it's slow music in a fast time.

[Laughs] Yes.

You are making music for an audience which makes the time to listen.

Yeah. We made my first two records with T Bone Burnett producing and I remember him encouraging us to be brave and saying, “You are not background music, someone has to decide they want to listen to this music”.

He would often call what we do “music for people who love music”, which is an interesting point because there are many people out there who listen to music but don't really love music. They just listen to it.

But then there are people who loooove music, and we are music for people who loooove music. It does ask a little bit of people, you have to slow down and make a bit of space in your life for it. Happily, once people do that and let our quiet panoramas unfold before them then it seems to sink in really deeply.

I have a great respect for our audiences because I think they love music and are well listened,. I feel with anybody at any of our shows I could sit down with their record collection and have a real good time.

One thing that occurs to me you came along at time when for a lot of people the uncertainties of the present meant they would look to the past for solace and certainty, yet when you sing older songs they don't celebrate the good old days but they are often songs with a lot of darkness about them. I'm curious as to how you read that, if that is true, that people find comfort in your songs even though they are uncomfortable.

Yes, I understand that, my current understanding of what Dave and I do is that our work has to unfold to us as well.

I feel a lot of our material acknowledges life's more challenging moments, but that the people in the songs are not quitting or giving p, there is a perseverance and stoicism. And even in a dark or sad song somehow I feel the person is going to make it through.

So it's okay to take four or five

minutes and be in dark or sad place, because part of getting through

it is understanding that it is happening and being comfortable with

that.

So it's okay to take four or five

minutes and be in dark or sad place, because part of getting through

it is understanding that it is happening and being comfortable with

that.

I always gravitate towards tragic, darker and slightly heavier songs. They meant a lot to me, they were a window on a world that I needed to understand as a part of life. That works for a lot of people, the blues are for real. [Laughs]

You have to have empathy for others in this world and a song can allow us into another person's world, even if they are imaginary characters, where we can feel some compassion.

I will ask you one more quick question: You have collaborated with a number of people but if there was one person out there right now you'd like to work with who might that be?

Oh, that's interesting. We missed our chance with a couple of them, Levon Helm and Allan Toussaint. We got to play with Levon . . . but every time we played he'd want us to form a band.

That's a drummer for you.

Oh, yeah. You know there are so many musicians out there we really like, but that's one of the great things about doing the Machine project, it's made it so we can get to play with a lot more people.

There is much more about Americana music at Elsewhere starting here.

post a comment