Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Come Rain or Come Shine

In recent times Mick Jagger has said he'd rather be interviewed by young journalists, because the old cynical ones are only ever interested in writing about the collective age of the Rolling Stones, which numbers in the centuries.

He has a point and, whether you care for them or not these days, the Rolling Stones still make energetic blues-based rock . . . and are even promising (threatening?) an album of new material by the end of the year.

So a young writer interviewing Jagger (age 72), might actually be interested in the music they make because it is energetic and driven as much from the groin as the guitars.

That would hardly seem to apply to the new albums by Bob Dylan (turning 75 this week) and Eric Clapton (71).

Neither have much, if anything, to do

with rowdy rock music and, the Dylan especially, both are certainly light

years from their styles in the Sixties – half a century and more

ago – when they sprang to attention as game-changing artists who redefined the project of what became rock music..

Neither have much, if anything, to do

with rowdy rock music and, the Dylan especially, both are certainly light

years from their styles in the Sixties – half a century and more

ago – when they sprang to attention as game-changing artists who redefined the project of what became rock music..

Clapton's I Still Do – perhaps the answer to an unasked question – understandably has its default position in blues of the kind which influenced him as a teenager.

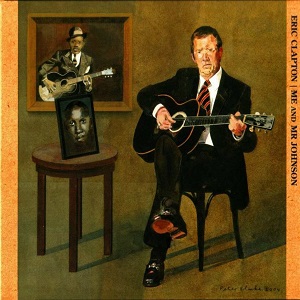

So here are songs by Leroy Carr, Skip James, Robert Johnson (whose songs he has always recorded but most notably on the tribute album Me and Mr Johnson) and the traditional country-gospel I'll Be Alright are here given Clapton's now familiar mid-tempo style where his guitar passages amble down familiar by-ways.

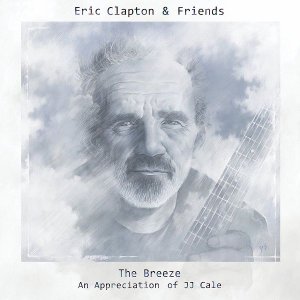

It is the late J.J. Cale whose presence

hovers over this however -- whom he has also previously paid tribute to on The Breeze -- and where Clapton sounds more energised.

It is the late J.J. Cale whose presence

hovers over this however -- whom he has also previously paid tribute to on The Breeze -- and where Clapton sounds more energised.

He and the finely-tuned band gets inside the swamp-funk groove of Can't Let You Do It and Somebody's Knockin', and Clapton writes the interesting Catch the Blues in Cale's intimate style.

At other times, as with the soulful I Will Be There (featuring the famously anonymous co-vocalist Angelo Mysterioso) and the old lullaby Little Man You've Had a Busy Day there is an ease which errs perilously close to MOR.

His guitar playing is best described as understated (has been for a while) and – as with older jazz players – comes from that less-is-more school where they say the notes you don't play are as important as those you do.

Well, that may be true . . . but

sometimes more-is-more and actually better.

Well, that may be true . . . but

sometimes more-is-more and actually better.

In many places here Clapton pulls right back on the guitar work, so when he lets go a little (his lyrically leaden Spiral co-written with band members Simon Climie and Andy Fairweather Lowe), on Skip James' Cypress Grove (with barrelhouse piano) and Johnson's Stones in My Passway there's a real sense of inspired and energetic engagement.

The final track, I'll Be Seeing You dates from the late Thirties and was famously sung by both Bing Crosby and Billie Holiday in the Forties. Here it sounds very much like a farewell from a man who has spoken of retirement.

Of this album the phrase “fits like a comfortable shoe” has already been taken (David Bauder), but words like subtle, refined and considered doubtless apply . . . and there is a religious sentiment as a subtext in places (Catch the Blues, the gospel I'll Be Alright, I'll Be Seeing You).

If this is his final album he's going out quietly with the customary modesty he has found in the past few decades.

He also drops in a fine, Band-like and accordion-coloured reworking of Bob Dylan's I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine which is warmer than Dylan's spare, folk-framed original.

Good to hear.

Because even Dylan – other than in his on-going touring – doesn't do much Dylan these days.

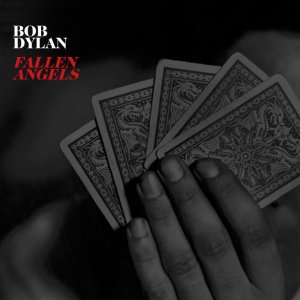

For his previous album, the excellent

and underrated Shadows in the Night of last year and Fallen Angels Dylan

has gone to the catalogue of songs associated with Frank Sinatra.

That Dylan might apply his sandpaper'n'whiskey voice (which is of

limited range) to songs from one of the great voices of the past

century might seem both foolhardy and courageous.

For his previous album, the excellent

and underrated Shadows in the Night of last year and Fallen Angels Dylan

has gone to the catalogue of songs associated with Frank Sinatra.

That Dylan might apply his sandpaper'n'whiskey voice (which is of

limited range) to songs from one of the great voices of the past

century might seem both foolhardy and courageous.

But, like Sinatra, Dylan starts with the story in the words, and brings a broken gravitas and often damaged, world-weary interpretation as befits a man of his experience and age. But there's also a reflective optimism here, as on the highly moving All the Way and especially the courageous opener Young at Heart, the man who wrote the modern standard Forever Young finding this companion piece as he looks back.

The losses of lovers are here (the achingly sad Maybe You'll Be There) as is the longing for love (Hoagy Carmichael's Skylark) and its discovery (Nevertheless given a somewhat plodding treatment). Not everything works: On All or Nothing At All he barely rouses himself for the lyrics and he seems like a passenger in That Old Black Magic.

But – like Clapton – he ends on a poignant note: a gorgeous treatment of Come Rain or Come Shine where the lyrics look forward (“I'm gonna love you . . .”) and although the voice suggests there might not be much more to come, the past has seen loving, comfortable companionship.

Bob Dylan has always looked back to

music from before his time (Woody Guthrie, ancient blues, standards

and old folk ballads have been peppered throughout his long career)

and found inspiration there.

Bob Dylan has always looked back to

music from before his time (Woody Guthrie, ancient blues, standards

and old folk ballads have been peppered throughout his long career)

and found inspiration there.

So here – and on the slightly superior Shadows in the Night – he sings as man who has learned the hard lessons of love and life and in these words he finds solace, and elegant writers who conveyed the hurts and happiness.

And, as before, he arranges these songs – which most would interpret as piano ballads or string-heavy weepers – for his band with fiddle and pedal steel.

Their gentle, sophisticated country sound softens and supports that cracked and weary voice which strains for notes at times (look to Polka Dot and Moonbeams which is like a charming grandad singing at a wedding to the embarrassment of the young couple). But these arrangements and settings further humanise these interpretations.

Given their lengthy, singular and undeniably important careers, neither Bob Dylan or Eric Clapton have anything more to prove to anyone, least of all at their age.

But here, Dylan especially, they sing from the point in life where they are at, not pretending to be anything other than what they are: dignified, wise, companionable and compassionate old soldiers knowing they are nearing the end of the long march towards the inevitable.

mason baker - May 23, 2016

Sounds worth a listen!

Savepost a comment