Graham Reid | | 11 min read

That Man is a Legend

For an interviewer, the worst subject isn't the one who doesn't say much or even anything, because at least that can be turned into a funny story. The worst is the person who just goes on and on and on . . .

Two-time Grammy-nominated American guitarist David Becker can certainly talk, but the saving grace is that he's very interesting, has enjoyed a real DIY career in which he sidestepped traditional paths, connected with his audience around the world in a different way and works hard at his job.

Sitting in Auckland hotel room back in mid-July the affable Berger acknowledged that when he's going to a new territory like New Zealand where his name may be unfamiliar, he's happy to come early and do interviews to prepare the ground.

With his group the David Becker Tribune, he will play shows in October (see dates below), but back in July he did interviews back-to-back over five days, took a master class for students at MAINZ, spoke to people in the jazz department at the University of Auckland and shook a lot of hands.

And – because he's done it this way for ,ore than three decades – he doesn't see any of this a chore, it just comes with the territory of being a musician. And he genuinely enjoys connecting with the guitar community and meeting students.

During his five days he also caught up

with a guitar teacher from Palmerston North whom he had met on-line

while doing some educational tuition.

During his five days he also caught up

with a guitar teacher from Palmerston North whom he had met on-line

while doing some educational tuition.

Becker – who has a dozen albums to his name, has played in over 20 countries and performed at some of the biggest jazz festivals and in the smallest school rooms – is a reach-out kind of guy and admits he is always looking for new ways to engage with people.

“You know, we've never recorded a live album with an audience and I think this is going to be the best place to do it. We'll tell people they are going to be on the album and it will come out next year and we will back then to promote it.

“Maybe I will write a tune for New Zealand and put it on the album too, that's the idea.”

Becker is a child of the post-rock'n'roll generation who grew up listening to his older brothers' records (Led Zeppelin, Hendrix etc), remember his conservative parents taking the kids to see the Beatles' Help! movie at a drive-in when he was about four, was a Monkees fan as a pre-teen but loves rock music (the week before we talk he'd been to see Bad Company) and yet the first album he remembers really affecting him was something different.

Because of his parent's listening taste the first record he remembers siting down and listening to every day was Edvard Grieg's Concerto in A Minor, "and I would conduct along with it,” he laughs.

He says even though he didn't know major and minor chords at the time but recalls a landscape painting in their house he would look at when listening: the dark areas were always associated with the minor passages and the towering mountains the majors.

“Music was always very visual for me.”

Although an early convert to jazz when he switched from trumpet to guitar at 15, he played “a little bit of rock and I'm a huge fan but I never found my voice in it”.

“When I started to play guitar I wrote these rock tunes and I could do pretty good blues impression but then I heard jazz on the guitar – Grant Green – and that made more sense to me. I'm a big fan of Mick Ralphs in Bad Company but that's not what my voice is. There is still some of that in there if you listen to what we've done over the last 30 years, it's not just jazz.”

Although the word has been attached to him sometimes, he rejects the word “fusion” as simply the invention of a record company to pigeonhole music for marketing purposes. Equally he dislikes “smooth jazz” because “all the players sound the same, you can't tell who's who”.

“Honestly, the thing for me is that I'm a jazz musician because I improvise, and improvisation is an integral part of the music. The influences are broad, they come from the Middle East to folk music and I'm not afraid to play what I like.

“When I play I don't play music as

guitar player, I play it as a fan of music.”

“When I play I don't play music as

guitar player, I play it as a fan of music.”

And in that he has followed his own path, often simply making his own when one didn't exist.

He was born in Cincinnati, Ohio but – because his father worked for an airline the family moved a lot, five times before he was eight and then settling in Southern California.

With his brothers Ed and Bruce – the latter drummer in the David Becker Tribune – he would make music, he starting on drums before moving to trumpet.

In junior high he was lucky enough to have an inspiration teacher who had played with Harry James, Stan Kenton and was connected with a lot of the LA classical and jazz players: “He would get these great arrangements and taught us the fundamentals of how to be a musician in a band and how your part was important for the sum . . . which as greater than parts.

“We talked about Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Miles Davis . . . so we knew those names.”

However in high school the teacher was a classical guy who presumed he'd join the orchestra, but that wasn't his thing so he quit trumpet, picked up guitar and kept going back to a rehearsal band his former teacher ran where students and professionals would sit in together.

He applied to Berklee and was accepted “but a guy I met who'd been there said, 'Don't go, it sucks, it's too cold in the winter, there are a million guitar players and you have to fight to get the teachers you want. Go to GIT [the Guitar Institute of Technology in Los Angeles], it is small and right in your back yard'.”

He visited the place in an area of LA he describes as “like a sewer” at the time, liked the small size (I had only opened two years previous in '77) and there were just 25 people in his class.

But even then he was very clear what he wanted to do: write his own music, make records and tour with his brother.

“The thing with young musicians is

they don't always know what they want, so I encourage them to find an

idea as to where they see themselves.

“The thing with young musicians is

they don't always know what they want, so I encourage them to find an

idea as to where they see themselves.

“I say to them, 'What do you want to do and how do you see yourself doing that?'. You have to have a very clear picture of what you want to do and never lose sight of it, and you also have to imagine yourself how it feels to do that because it is always ahead of you.”

With that kind of self-insight Becker applied himself to getting work and experiences, although he says he was never that interested in just playing the LA club scene. His horizons were wider and further afield for the band he formed as the David Becker Tribune.

Tribune?

“Yes, two stories behind that. When we put the band together the bass player said he'd always liked the word tribunal because it was a three-man governing thing or whatever it is. And I had a summer job working for the Daily News in LA doing stuff in the office when I was a student . . . and it was in the Tribune company and I liked that

“I thought when I start a band I don't want it to be the David Becker Trio because . . . just another trio, isn't it? People now refer to as the DBT or the Trib.”

After the year at GIT he started putting himself out there although says he could go back and hang out with the likes of Robben Ford, Jeff Berlin, Steve Morse (“We were labelmates for a while”) and others.

But he got little TEAC four-track, made some made demos and because his father worked for the airlines he could get cheap flights to Europe, so at 19 went over looking for a record label that would sign him.

He met people from ECM and Enja who were encouraging but then had a couple of lucky breaks, which in a sense he capitalised on.

His band's original bass player was a friend of Chris Martin of Martin Guitars and he was invited to play at guitar trade fairs and – although the company had never used people in ads previously – they were going to use Yes guitarist Steve Howe.

Becker was invited to be in an ad with Howe so he appeared in Guitar Player and Circus magazine “but people of course asked, 'Who is this guy? What does he do?' so that worked for me.

At the same time he was hooked up with German who ran a vegetarian restaurant The Come Back Inn in Venice Beach who had the likes of Charlie Haden and Latin American bands playing regularly.

“His stipulation was you had to play original music because he didn't want to pay the BMI fees, so that was perfect for us!

“It was a great breeding ground and played one or two times a month for a year, so at some point I'd get a folk harp and put it through a delay, or play trumpet and just experiment. I noticed more and more guitarists were coming to see us play.”

In '84 a promoter friend asked if the group wold be interested in a tour of Germany – where Becker had been and played trade fairs – but at the last minute the promoter dropped out so he picked it up.

“I was 22 and I have no idea how I did this but I managed to put together a two week tour, but at that time in your life you are too stupid to know what you can't do . . . so you just do it.”

Friends of friends in the States and Germany gave him numbers to ring and they scored some studio time at Warner Brothers studio and did an all night session of five tunes direct to digital two-track.

“That became our first EP, it was never released but we could use it for radio promotion so we sent that to Radio Free Berlin.”

The tour worked, they returned to the States and their manager booked them into colleges all across the East Coast and Midwest.

“We must have played about 70 colleges in six months. They out us in lunch rooms, in little theatres, and the radio stations would support us with interviews and playing the music.

“By the time we got back to the West Coast after six months of touring we were a well-oiled machine. We'd bought a van in Germany because the dollar was so high at the time that it was cheap and we had that brought over.”

Then an engineer at MCA Chet Himes

invited the band to do a 32 track full digital album “and that

because Long Peter Madsen, our first album on MCA. I never thought

I'd be on anything other than a small jazz label, I mean I was

talking with Enja but I had offers from people that didn't work out.

“But I was 22 and thinking I needed to get a record out and that

came out in the summer of '85, the time of Live Aid.

Then an engineer at MCA Chet Himes

invited the band to do a 32 track full digital album “and that

because Long Peter Madsen, our first album on MCA. I never thought

I'd be on anything other than a small jazz label, I mean I was

talking with Enja but I had offers from people that didn't work out.

“But I was 22 and thinking I needed to get a record out and that

came out in the summer of '85, the time of Live Aid.

“We were in the studio and next door was the heavy metal band Dokken and one tune on the album Chet Himes took my guitar signal and ran it through [Dokken guitarist] George Lynch's cabinet and put a little distortion on it.

“MCA had resurrected their jazz division at that time and had Spirogyra and had signed Michael Brecker, Jack DeJohnette, the Yellowjackets . . . and they saw that we were getting gigs and on the road – they had guys twice my age couldn't get gigs – so they signed us.”

The album was a critical success and the DBT or Trib as they are sometimes known were opening for their labelmates and touring constantly, often creating their own gigs.

“I had to open solo for Miles Davis and Chick Corea's new trio at one festival. I played solo for 10,000 poeple. I wasn't nervous but I worked out a little set and they needed the 30 minutes filled because they were filming it for TV and they needed to move the sets.

“I didn't have time to be nervous, the thing I learned abut communication is if there's a big sea of people you want to reach that guy in the 37th row and you are going to play for him, so I just started to play.”

Becker says what he learned in all those years was that it is important to communicate from the stage and that it doesn't matter if you are in a Lear jet or a little bus, it is the same. The things you have to do don't change because your day-to-day life is on the road and you are flying by the seat of your pants.

“Now instead of driving 16 hours I

fly for 16 hours, “ he laughs, “but after 30 years I'm very

appreciative that I can still do this, there are still pockets of

places where people are interested in what I do. And new places too.

“Now instead of driving 16 hours I

fly for 16 hours, “ he laughs, “but after 30 years I'm very

appreciative that I can still do this, there are still pockets of

places where people are interested in what I do. And new places too.

“That was my goal anyway, that was what I wanted to do.

“And when you are touring no matter how well organised you are stuff can happen. A guy told me that Chick Corea showed up to a gig at the wrong venue on the wrong day!

“So when we got that record deal with MCA we were ready to go and there were a lot of jazz radio stations, most cities had two and some were contemporary and others were traditional, but we kind of fitted in the middle.

“I never gave any thought to fit into a format but for the first four or five years we did almost an album a year and gave a lot of thought to what we wanted to do for ourselves, which was just good music and not catering for a radio station.”

Albums by the David Becker Tribune have consistently climbed the US jazz charts, his workshops and their concerts have won global acclaim, he and his brother based themselves in Europe in '92, they played six dates in Russia in '94 and have been to Argentina 10 times, he has endorsed Bose speakers and most recently he has a signature guitar in the Heritage catalogue.

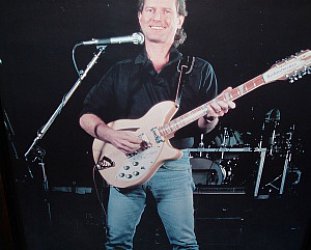

When he tours he carries just one

guitar which he refers to as his “million-miler”, which he

happily pulls out for a photo. It is a solid maple machine made in

'88 out of which he can get acoustic and electric sounds.

When he tours he carries just one

guitar which he refers to as his “million-miler”, which he

happily pulls out for a photo. It is a solid maple machine made in

'88 out of which he can get acoustic and electric sounds.

As a self-starter who has played in offices for the sales people who are promoting his records or going into Tower Records to make sure his albums are there, and maybe playing for staff, Becker has a keen eye on how the marketplace fro jazz has changed, and how you need to keep ahead of the curve.

“CDs still have a place,” he says, “because you can't sign an MP3 after a show. I've had people come to my concerts and tell me they buy my stuff on iTunes but at a show they want a physical copy.

“There are a bazillion David Becker Tribune clips on You Tube and even on the Weather Channel where people put on snippets of ours stuff, but people still buy the music and we can follow the digital sales and watched them go up.

“We can still do things to our advantage but you have to be diligent about it and think, 'How are we going to do this?'

“I don't subscribe to that idea they you can't do it, we just went out and did it. You have to be tenacious. If someone says, 'Great, we'll call you' and you sit on your sofa and wait for the phone to ring you might as well forget it.

“You've got to keep the relationship going. You have to get out there and work for it all the time.

“But if this is what you want to do in life, then why would you now work for it?”

DAVID BECKER TRIBUNE NEW ZEALAND DATES

Juice Bar, 144 Parnell Road

post a comment