Graham Reid | | 4 min read

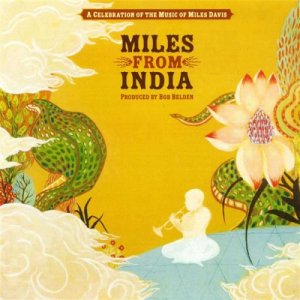

Miles From India

For very many decades there has been a profitable and important cross-cultural engagement between Western musicians and Indian artists.

From the moment people heard George Harrison tentatively picking out a few notes on sitar for the Beatles' Norwegian Wood in 1965 – and unwittingly launching a raga-rock phase which dominated the late Sixties – the influence of Indian music infiltrated the global pop-rock scene.

It was notably evident the British folk world through groups like The Incredible String Band from Scotland, sitar player Shawn Phillips from the United States (who performed with Donovan) and of course the Beatles, especially Harrison whose extraordinary Love You To in '66 (on the Beatles' Revolver) owed nothing to Western pop and was based on Indian musical form.

That same year in the classical world the American composer Philip Glass worked on the film score for Conrad Rooks' cult film Chappaqua with its composer, the sitar master Ravi Shankar and tabla genius Allah Rakha.

Shanker and Glass would subsequently record together (Passages in '90) and the sitar player/composer was a great populariser of his instrument and Indian music.

Shankar played at various rock festivals (not always happily as he

told me and anyone who would listen). He recorded albums with the

London Philharmonic Orchestra under Zubin Mehta and the London

Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andre Previn, there were albums with

violinist Yehudi Menuhin . . . and as far back as '62 he wrote the

groundbreaking piece, Fire Night, to be played by an Indian

percussion ensemble and a small jazz group of Bud Shank (flute),

Dennis Budimir (guitar), Gary Peacock (bass) and Louis Hayes (drums).

Shankar played at various rock festivals (not always happily as he

told me and anyone who would listen). He recorded albums with the

London Philharmonic Orchestra under Zubin Mehta and the London

Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andre Previn, there were albums with

violinist Yehudi Menuhin . . . and as far back as '62 he wrote the

groundbreaking piece, Fire Night, to be played by an Indian

percussion ensemble and a small jazz group of Bud Shank (flute),

Dennis Budimir (guitar), Gary Peacock (bass) and Louis Hayes (drums).

Jazz musicians have long been drawn to Indian music: both jazz and the Indian classical tradition of ragas (and to a great extent the folk style dhun) being largely improvised.

The saxophonist John Coltrane briefly “studied” Indian music (“discussed” might be a better description) with Pandit Ravi Shankar in the mid Sixties (he'd heard the music some years previous) and was drawn to Indian harmonics (and the spiritual elements of Indian philosophy).

Around the same time the Jamaican-born, British-based saxophonist Joe Harriott and Indian violinist/composer John Mayer formed the group Indo-Jazz Fusions for recording and touring, the ensemble made up of Western and Indian musicians.

But what is most notable in any overview is how it is just the melodic aspects of Indian music which Westerners explore and incorporate into some kind of fusion music, sometimes merely for exotic effect.

The complex rhythmic patterns in Indian music from tabla (the twinned drums played by hand and a cornerstone of Indian percussion) are much harder to accommodate. Certainly many Indian tabla players like Zakir Hussain have brought their rhythms and sensibilities to ensembles of jazz, rock and world music players.

But for the most part tabla has been used simply to bring emotional

intensity — as in Quincy Jones' soundtrack for the '67 film

adaptation of Truman Capote's In Cold Blood – or for some exotic

effect.

But for the most part tabla has been used simply to bring emotional

intensity — as in Quincy Jones' soundtrack for the '67 film

adaptation of Truman Capote's In Cold Blood – or for some exotic

effect.

So, setting aside the complex bottom end of rhythm beyond time-keeping, we come to the album Miles From India released in 2008, a large and interesting work produced and helmed by Bob Belden in which Miles Davis' music – some of it his modal style, of course – gets a makeover by Western jazz players (some like John McLaughlin entirely in tune with Indian music) and Indian players.

It would be hard to imagine anyone more attuned to Davis' music than Belden who has been helming the expansive reissue of Davis' work, and the Western players he dialed up were also fellow travelers with Davis, among them guitarists Mike Stern (who here gets to again play Jean Pierre, albeit in a much more considered way than his alienating work on the live version on We Want Miles) and McLaughlin, bassists Ron Carter and Benny Rietveld, drummers Jimmy Cobb and Lenny White, tenor player Dave Liebman . . . and the trumpet part – on just five of these 12 interpretations -- falling to Wallace Roney.

Miles Runs the Voodoo Down with Roney is the ideal starting point for those sceptical about such a project: Roney plays a straight bat to his part while underneath two Indian percussion players lay down a deep and different groove alongside Lenny White and, with Pete Cosey's twisting guitar shapes and Adam Holzman's swathes of keyboards, the whole thing sounds like an outtake from the Bitches Brew sessions.

Elsewhere the Indian musicians are much more to the fore: The brief

In A Silent Way is fronted by sarod player Pandit Brij Narain and

acts as a scene setting bridge into the intensity of It's About That

Time where Indian violin (Kala Ramnath), Cosey's searing guitar and

alto (Gary Bartz) go head-to-head in a thrilling encounter where each

gets a chance to stand at the centre of the frame. Cosey's playing

can be downright strange but never without interest across this

impressive concept , which came as three record box set with a

beautiful booklet containing a lengthy essay by Belden.

Elsewhere the Indian musicians are much more to the fore: The brief

In A Silent Way is fronted by sarod player Pandit Brij Narain and

acts as a scene setting bridge into the intensity of It's About That

Time where Indian violin (Kala Ramnath), Cosey's searing guitar and

alto (Gary Bartz) go head-to-head in a thrilling encounter where each

gets a chance to stand at the centre of the frame. Cosey's playing

can be downright strange but never without interest across this

impressive concept , which came as three record box set with a

beautiful booklet containing a lengthy essay by Belden.

All Blues

All Blues opens with a melodic line being tickled out by sitar player Ravi Chary (in the manner of a raga) before the familiar groove kicks in and Chary takes over the tune. In many ways it is the most conservative piece here, alongside the 20 minute Spanish Key which – despite the presence of an Indian percussion ensemble, sax and singer Shankar Mahadevan, and two players on Indian flute, one being Dave Liebman – keeps close to the template.

Miles' one-time pianist Chick Corea also appears, but just the once on a very tasteful So What over percussion (and those sung rhythms which are a feature of Indian music). It is only one of three of Davis' compositions from Kind of Blue here however.

That Belden has reached beyond the obvious Kind of Blue material for this project is testament to the reach of the players and Davis' compositions, and the only new piece here is the title track written by McLaughlin, a reflective piece with U Shrinivas on mandolin, Louis Banks on piano, McLaughlin himself on guitar and the yearning vocals of Sikkil Gurucharan.

It is a fitting, respectful but also deliberately boundary-pushing closing piece on a project which effects a very special meeting of East and West.

There is a considerable amount on Miles Davis (including an interview) at Elsewhere starting here.

And for more on Indian music -- including an interview with Ravi Shankar -- go here.

post a comment