Graham Reid | | 5 min read

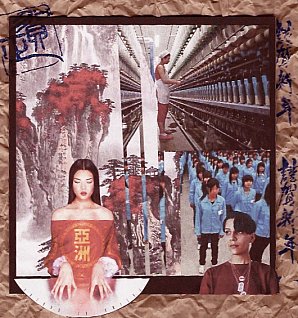

Shanghai Freeway

When Aaradhna was awarded but declined to accept the best urban hip-hop award at the 2016 New Zealand Music Awards for her album Brown Girl – saying, among other things she was a singer not a rapper and that she felt marginalised by being put in what she saw as the “brown” category – it set off a small debate about how we label music and artists.

Unhelpfully some weighed in saying all awards are stupid/all music should be treated the same/etc but that fails to acknowledge that categories – like them or not – are actually helpful to artists and audiences.

Certainly at one level they are just taxonomic devices but they help listeners gravitate to their area of choice. Yes, of course we'd prefer people listen to al kinds of music but that idea has long gone because of the balkanisation of radio, music television and artists themselves.

It helps listeners if a writer mentions “alt.country” or “disco” because if their natural inclination is to run a mile from those genres then they needn't waste any further time.

Of course within music today there are numerous subsets – metal shaved off into death/black/nu- etc, jazz into Dixieland, bop, free jazz etc – and that refines the genre even further. Helpfully, I would suggest.

If artists don't want to be in a genre – as Aaradhna didn't, although she and her management actually entered her name for consideration – that can be a problem. But categories are here to stay.

Not that they are immutable.

In New Zealand when the Warratahs were at their peak and Al Hunter was recording damn fine albums, the “Roots” category at the awards meant country music (and its offshoots). The category disappeared for a while and when it returned it mean reggae . . . and that has been the case for many years now.

We who read the reviews and music press assiduously long ago accepted “post-rock” . . . although recently “post-jazz” bewildered me. But if it is a useful label to get music into people's ears then so be it.

One of the more knotty genres is “world music” because at core it seems to mean – but not always – music not coming out of the Western axis of Britain/the USA/Canada/Australia and New Zealand. Although an interesting question to ponder is this: Is Maori music world music?

Answer perhaps? Not in Aotearoa New Zealand, but probably everywhere else.

It is possible to pin down exactly where and when and why the label “world music” was created. And, like al the best ideas, it happened in a pub.

It happened on June 29, 1987 at the Empress of Russia in Islington, North London.

There was a gathering of like-minded people from various record companies, labels, concert promotion companies and festival organisers who had spent years trying to “sell” the idea of music outside of pop and rock. Music and musicians from Africa, India, the Pacific and so on. From all around the world, in other words.

They came up with a marketing strategy.

One of the problems perceived as hindering the development of this music was the haphazard racking in record shops. It was agreed the term ‘world music’ would be used by all labels present to offer a new and unifying category for shop racking, press releases, publicity handouts and ‘file under’ selections.

This “catch all” description was created which would include everything from Indian classical music to Bulgarian choirs, and music in te reo, Samoan, Wolof and so on.

Today world music is so huge that the various regions, countries and regions within countries are often clearly identifiable.

So “world music” perhaps isn't quite as helpful as it once was, but it also doesn't need to be. If you want Indian music you know where to find it.

But increasingly artists who were once considered “world music” are now beyond even more precise genre identification.

Perhaps they, like singer/composer Fatima Al Qadiri are “post-world music”?

Born in Senegal, she grew up in Kuwait, got a degree in linguistics from New York University and shortly after, in 2009, emerged as an electronica and multi-media artist producing sculptural and video installations.

She is also a sometime

member of the hip-hop outfit/collective Future Brown which included

the Chicago rapper Tink on their single Wanna Party. (Incidentally FB

were championed by Red Bull and used in their promotions, but their

2015 debut album rose without a trace and was met with some critical

dismissals . . . and useful controversy ensued.)

She is also a sometime

member of the hip-hop outfit/collective Future Brown which included

the Chicago rapper Tink on their single Wanna Party. (Incidentally FB

were championed by Red Bull and used in their promotions, but their

2015 debut album rose without a trace and was met with some critical

dismissals . . . and useful controversy ensued.)

Al Qadiri is a prolific and intelligent blogger, but has only released one full album, the fascinating Asiatisch in 2014.

It is – as you might expect from that long preamble about labels – one of those albums which denies genre.

But when it comes to sub-genres it is in the park labelled “sinogrime”, UK grime which adopts musical motifs and ideas from China.

So here is a New

York-based musician who takes a German word for her album title (it

means “Asian”) and makes an album based on a journey through the

China of her imagination, and uses UK urban grime as her vehicle.

So here is a New

York-based musician who takes a German word for her album title (it

means “Asian”) and makes an album based on a journey through the

China of her imagination, and uses UK urban grime as her vehicle.

Oh, and the opening piece Shanzhai is her re-imagined cover of the Prince/Sinead O'Connor song Nothing Compares to U with made-up Mandarin-sounding lyrics over a wide and soft mattress of electronica. It is interesting enough but is actually the least compelling piece among the 10 on the album.

Szechuan which follows is a bridge between Middle Eastern melodies, allusions to throat singing and a light tough of space-ambience. Yet there is something menacing here too. Dan Barrow writing in The Wire heard “war marches, lines of commerce and military power marching across the virtual maps of worried finance magazines”.

That seems a considerable leap, but even in the more whimsical pieces (the mildly disorientating Wudang with its vocoder and beats) she undercuts with downbeat assertion.

She explores her fanciful China – call it electronica Chinoiserie if you will – to pull out a pan-cultural exoticism but also deals with the cultural collisions of West and East in the high-powered 21st century.

At one level it could be criticised as cultural appropriation or cultural tourism, but Al Qadiri is too smart to fall for mere borrowings and recastings. The music exists on its own plateau, always referencing but never merely adopting.

There is a subtlety here

which, unfortunately, was missing from her much less nuanced and

overtly political Brute follow-up in 2016.

There is a subtlety here

which, unfortunately, was missing from her much less nuanced and

overtly political Brute follow-up in 2016.

Brute also felt emotionally detached – not a good thing when the agenda was political engagement – but that distance suits the more dreamlike quality of Asiatisch. Often the music of Asiatisch feels like the sound design for a strange and stateless film (Hainan Island has dark sonic fog horns but a lightness of melody from could almost be electro-marimba) and the fleeting suggestions of temple gongs or flutes – all electronically realised – further add to the aural illusion of some distant place in the half-remembering.

The 10 pieces are all part of an integrated whole also where melodic ideas re-appear in different contexts, or those menacing minor key synth intrusions add gravitas to the tunes drifting over the beats.

And damn if Shanghai Freeway doesn't owe just a smidgen to the minimalism of Kraftwerk, albit with that Chinoiserie influence.

Asiatisch is one of those frequently ambiguous albums which gives up a little more on each hearing and it is most definitely an album to be listened to and assimilated slowly.

Post-world music, perhaps?

post a comment