Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Montana (from Raygun Suitcase)

When Pere Ubu emerged out of Ohio in the late Seventies one British writer described them as “the sound of things falling apart”.

But while that was true, they were always more than that: Their sound was immensely and deliberately unnerving.

Frontman David Thomas yelped like a dog, barked like a madman or went so quiet and low – before yowling into the endless existential night – that you never quite knew what to feel.

You were certainly made to feel something, but by the very nature of what they did Pere Ubu went past many people.

In the post-punk days they were embraced by those in search of something beyond pop and rock (the easily comprehensible stuff) and as such were the darlings of people whose listening parties you'd want to avoid.

Which means Elsewhere has not only previously addressed the two earlier vinyl box set reissues by Pere Ubu -- wouldn't cross the bar to hear blather from the Fall's Mark E Smith -- but we have interviewed Thomas at length back in '99 and then last year about the reissues.

We won't go back to him again . . .

But those two vinyl box sets allowed us to reconsider (here and here) that “sound of things falling apart” comment. And find it wanting.

As we mentioned to Thomas in the more recent interview, we here fell for the noise but somehow missed the frantic dance quality of their music. And how they devolved the idea of pop music and pure noise being able to occupy the same space.

Ornette Coleman once said, “Remove the caste system from sound” and he meant it in reference to his harmolodic theories.

Thomas might well say something similar, but his is an even more democratic notion: that all sounds – whether they be disco or the noise of a fireworks factory exploding – are created equal.

So Thomas/Ubu have used their ideas and influences that way.

If their earlier release in that first box set were challenging, it is worth observing that over the decades their noise/music became more approachable, and Thomas' professed love for pop music came more to the fore in the song structures.

Perhaps increasingly familiarity was the reason they became more easy to listen to (but never easy-listening), but it's certainly true that an album like Raygun Suitcase -- which is first up in this new box set -- is rather chockfull of pop songs, albeit disturbing, fragmented pop songs punctuated by sonic intrusions, and also driven by some pretty widescreen guitar riffs. There are points in Beach Boys and Memphis where if you'd just dropped the needle at random you'd not think it was Ubu if you only knew their pivotal work before '82.

But we are getting ahead

of ourselves.

But we are getting ahead

of ourselves.

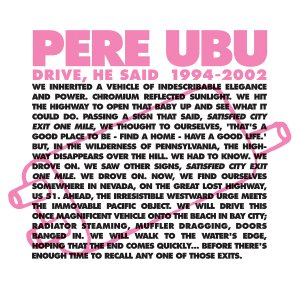

The Drive, He Said 1994-2002 box (taking its title from the Robert Creeley poem) includes the remastered Raygun Suitcase ('94), Pennsylvania ('98) and St Arkansas ('02). The final record Back Roads is a collection of live-in-the-studio songs, jam sessions and newly remixed pieces.

By this time Pere Ubu had an increasingly stable line-up of bassist Michele Temple, synth/theremin player Robert Wheeler and drummer Steve Mehlman and you can feel that lends more cohesiveness to these albums.

Although the guitarist were always a revolving roster. Here are Jim Jones then longtime player Tom Herman (back after about 20 years)

These are actually very approachable albums . . . except when they aren't. But that comes with territory.

Thomas delivers surreptitious menace more frequently than Lou Reed could ever muster despite his best efforts, and yet here his gargling, irritated, snarky and joyful singing is placed in pop-rock contexts quite often.

Raygun Suitcase has 12 songs in 44 minutes (although a couple of songs like their cover of the Beach Boys' Surfer Girl have been shifted to Back Roads), which is not that different to what the Beatles were delivering 30 years previous.

There's a difference, of course, and we leave you to discover that on album which is the sound of things having fallen apart being pieced together again into something approaching a cohesive shape.

Curiously the current critical perspective is that Raygun Suitcase was a return to their more aggressive early sound but to these ears it seems almost courageously mainstream, even if it is still swimming against the tide.

Thomas has always referenced popular culture, icons and places . . . and Pennsylvania – which includes songs with titles Silent Spring, Muddy Waters and Indiangiver – opens with the bludgeoning Woolie Bullie, not Sam the Sham but a hellish, spoken word vision over brittle guitars from an acid damaged, misanthropic character lost on a desert a highway: “We are abandoned . . . culture is a weapon that is used against us, culture is swampland of superstition, ignorance and fear. Geography is a language they can't screw up . . .”

Then a massive sustained organ chord smashes in (Sham Sam?).

It's very, very worrying.

When he says, “History is rewritten faster than it can happen” you get a very contemporary chill down into your frozen, clamped-tight Trump-era colon.

The abruptness of its ending is no solace, nor is the 90 second distorted semi-acoustic pop ballad Highwaterville which follows. It doesn't sound a safe place between Vegas and Los Angeles either, the person floating face down may well be the clue.

Pennsylvania – the name is worth thinking about – offers a grand and sometimes throttling sweep of America, and at this time Thomas quit his homeland for England (where he still lives).

Thomas sings less –

speak-sing had become his forte, like Lou Reed – and Wheeler's

theremin and keyboards add an otherworld feel here (Indiangiver at

less than a minute).

Thomas sings less –

speak-sing had become his forte, like Lou Reed – and Wheeler's

theremin and keyboards add an otherworld feel here (Indiangiver at

less than a minute).

One of those cases where distance lends disenchantment to the view, but with a pop consciousness you understand (Joke! Although Monday Morning is on my dyspeptic hit-parade).

St Arkansas continues Thomas and his fellow travellers' outsider view/sound but in many ways adds little to all that had come before . . . but by this time there had been almost three decades of gauntlet-throwing (and their bewilderment that only such a selective audience had picked it up).

Doom, gloom, satire, misanthropic humour (check the Talking Head-gone-acerbic Slow Walking Daddy on St Arkansas), dysfunctional pop and having Eraserhead competing with Shindig on your viewing preferences probably makes your references more interesting . . . but somewhat limits your audience.

And here's the joke if you haven't got it so far.

The opening piece on the nine-song Back Roads record in the box is the seven and half minute, mostly instrumental Ellipsis . . .

That album includes an extraordinary, increasingly demented version of Brian Wilson's Surfer Girl sung by someone like an even lesser Travis Bickle trapped in an innercity tenement block watching this unobtainable Californian blonde object on a black'n'white screen . . .

Listen to his Surfer Girl and think about that ellipsis . . .

Surfer Girl, by Pere Ubu

Pere Ubu – as always far too much music, information and exceptionalness -- collected in another box for them what cares.

Caring costs of course (four records inna box) but in their own way Pere Ubu have always been . . .

. . . “priceless?” . . .

post a comment