Graham Reid | | 12 min read

Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds (take 1)

Yes, it's been half a century

since this game-changing album of psychedelic whimsy, charm, poetry and studio

innovation was released.

It now gets multiple

re-presentations from single CD and vinyl (remixed in stereo by Giles Martin,

son of the Beatles' late producer George) through double disc iterations to a

large box set edition of four discs with never bootlegged outtakes, memorabilia,

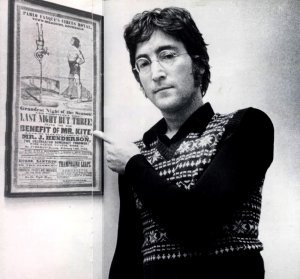

Mr Kite circus poster and more.

And although this comes from

a very different time ("it was a hit before your mother was born" as Paul McCartney later sang), Sgt Pepper remains an extraordinary synergy of diverse

songs, characters, effects, arrangements, production and packaging. Even more

so now perhaps with the stereo remix by Giles, who also created the mash-up Love

album.

The new mix certainly brings

up fresh sounds – notably Ringo Starr’s quite extraordinary drumming – but also

reflects the Beatles (and many fans’) belief that the mono Sgt Pepper is more

interesting than the stereo edition. Martin has kept mono in mind by placing

some vocals at the centre of the sound but also allowed the depth of stereo

(and the panning of vocals in key places) to remain intact from the stereo

remaster.

The new mix certainly brings

up fresh sounds – notably Ringo Starr’s quite extraordinary drumming – but also

reflects the Beatles (and many fans’) belief that the mono Sgt Pepper is more

interesting than the stereo edition. Martin has kept mono in mind by placing

some vocals at the centre of the sound but also allowed the depth of stereo

(and the panning of vocals in key places) to remain intact from the stereo

remaster.

Although the huge box will be

for completists with its dozens of alternative versions and outtakes, the double

CD/vinyl version is the way to go for older fans and the casual or simply

curious . . . because the second disc is the album constructed from alternate

takes.

And there are wee delights to

be discovered, for example at the end of the take of the opening title

track/welcome – where there are no brass instruments and an extended guitar

part – it ends with a guitar jam and McCartney chanting “free now, gotta get free

now”, a sample of which appeared on his Liverpool Sound Collage album in 2000.

And with some of the maelstrom of sonic psychedelics and cut-up tapes, orchestration and in some instances lyrics removed, much of the remaining raw music is unpredictable and simply strange. Or reductively simplistic as in a vocal-free take of McCartney’s Penny Lane.

And at the close of the "reconstructed outtakes" album rather than the famous slow-fade piano we hear the Beatles' first experiment, a protracted hum/Om.

There are also early versions

of John Lennon’s Strawberry Fields Forever before studio magic and pitch-changing

took it from a somewhat fast and anxious-sounding folk-rock song into the classic

of half-awake reverie that we know.

Sgt Pepper is of course the

concept album that wasn’t: the conceit of the Beatles now being Sgt Pepper’s

Lonely Hearts Club Band lasts no further than the cover, the first two songs

and the reprise of the title track.

It’s not hard to imagine how, if they had wanted to, they might have

reconfigured the album with segues to thread together a more coherent concept:

Possibly McCartney’s jaunty music hall-inspired When I’m 64 (the music for

which he had written as a teenager) might have followed Ringo’s turn as Billy

Shears on With a Little Help From My Friends and then perhaps moved into the

psychedelic and escapist pastoralism of Lennon’s Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.

Maybe it’s not even too much of a stretch to conjure up an acerbic Lennon at the start of

side two announcing “it is my pressure to bring on Harry Georgeson and His

Eastern Ensemble with exotic dancers” before George Harrison’s Within You and Without

You.

But the Beatle were never much attached to the idea of a concept album

beyond the little that McCartney had.

And they didn’t try much harder for Magical Mystery Tour later that year

either.

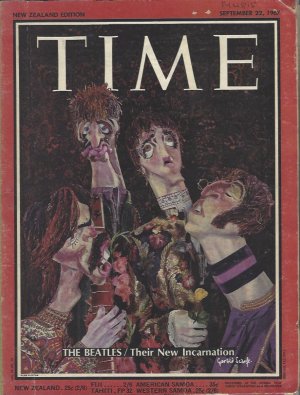

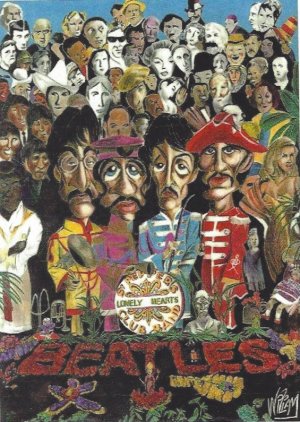

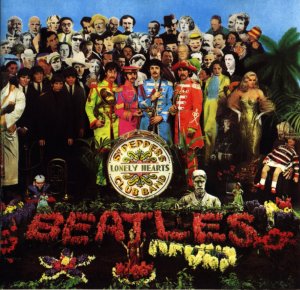

So Sgt Pepper remains a solitary landmark in the Beatles’ career, so

important that three months later when the impact and enduring qualities of the

album – almost three million sold in the US by that time – had sunk in it got

them on the cover of Time (life-size torsos by Gerald Scarfe of the Beatles in

papier-mache and exotic costumes) with a five-page article inside.

So Sgt Pepper remains a solitary landmark in the Beatles’ career, so

important that three months later when the impact and enduring qualities of the

album – almost three million sold in the US by that time – had sunk in it got

them on the cover of Time (life-size torsos by Gerald Scarfe of the Beatles in

papier-mache and exotic costumes) with a five-page article inside.

It described the group as “messengers from beyond rock’n’roll, they are

creating the most original, expressive and muscially interesting sounds being

heard in pop music . . .”

The article also said Sgt Pepper “more than anything dramatizes, note

for note, word for word, the brilliance of the new Beatles”.

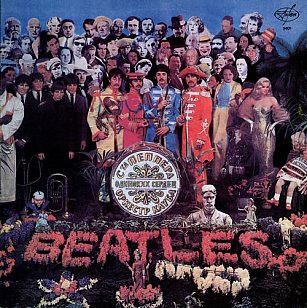

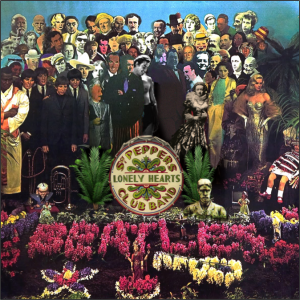

And the album – wrapped in a celebratory and colourful sleeve which

seemed generations away from their monochrome cover of With the Beatles just

three years earlier – reset the parameters of what was possible within popular

music.

This was music through a looking glass of colours, imagery, characters

and laborious studio production. As Ringo Starr remembered it later, it was the

album where he learned to play chess.

Their debut Please Please Me took a total of 14 hours, Sgt Pepper over

three months . . . and they also spun out the classic double A-side single

Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields Forever in advance of the album’s release.

Many writers have recently been quick to claim Sgt Pepper as one of the

most important, if not the greatest, in rock history.

But that assessment is as rooted in the past as the album itself: Certainly

for two decades after its release it topped critics’ polls -- which is hardly

popular consensus – but those days are long gone.

Today you rarely hear any of its songs on radio – was A Day in the Life

ever played after ’67? -- and more recent polls of the public and critics don’t

rate it as the greatest album of the rock era, and most not even as the best

Beatles’ album.

Last year the writers and critics poll in Britain’s Uncut magazine put their

Revolver – released the year before Sgt Pepper -- in second place (behind the

Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds of the same year) and further down their self-titled ’68

double album (aka The White Album) was in fifth position.

Last year the writers and critics poll in Britain’s Uncut magazine put their

Revolver – released the year before Sgt Pepper -- in second place (behind the

Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds of the same year) and further down their self-titled ’68

double album (aka The White Album) was in fifth position.

Rubber Soul of ’65 was 15th . . .

and Sgt Pepper only made it to 21st.

A decade previous Q magazine presented their “100 Greatest Albums Ever”

and Sgt Pepper came it at 19 behind Revolver (at 4) and Abbey Road (14) in a

poll topped by Radiohead’s OK Computer.

Back in 2003 Q magazine invited readers to vote on the best albums and

Sgt Pepper came in at 15 (Revolver in at 3 and Nirvana’s Nevermind topped the

survey). And in the late Nineties when the same magazine picked “The 50 Best

British Albums Ever” it didn’t appear at all.

Oasis’ Definitely Maybe beat out Revolver, the only Beatles’ album to

apear.

Those results – notably who topped those polls as much as where the

Beatles came – suggest the reason for the decline of interest in this masterpiece

of musical production. It’s that while it captured the spirit of Britain’s

Summer of Love, the world moved on.

New generations found their own soundtracks and those for whom Sgt Pepper

was a landmark slipped into old age and history, just like the album itself.

In 2010 the late Robin Gibb noted how often Bee Gees songs were played

on radio as opposed to Beatles songs. Citing the Beatles’ classic single

Strawbery Fields Forever released just ahead of Pepper he said, “Beatles’ music is very fixed in its time . . . Stayin'

Alive doesn't sound out of place [on radio], but Strawberry Fields would.”

And Pepper is idiosyncratically

a British album, despite it not being among Q’s best of British.

In America, they heard and

created their music very differently in ’67: It was the San Francisco hippie

era with bands like Jefferson Airplane, Moby Grape, Quicksilver Messenger

Service and Grateful Dead. Long guitar solos were the order of the day in the

USA and the street slogan was Timothy Leary’s “tune in, turn on and drop out”.

In America, they heard and

created their music very differently in ’67: It was the San Francisco hippie

era with bands like Jefferson Airplane, Moby Grape, Quicksilver Messenger

Service and Grateful Dead. Long guitar solos were the order of the day in the

USA and the street slogan was Timothy Leary’s “tune in, turn on and drop out”.

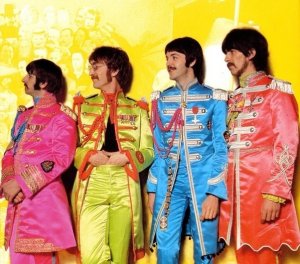

But the Beatles’ Britain had

a very different take on the psychedelic era: Visually it was a bright mix of

Edwardian foppery and recycled military uniforms from Carnaby and Oxford

Streets (Jimi Hendrix’s famous jackets and the Beatles' band uniforms on the

Pepper cover).

There was also a droll

detachment and studied eccentricity.

Even the previous year there

had been cynicism (Donovan’s Season of the Witch with its line, “beatniks out

to make it rich”) and jibes at the emerging culture of decadent dressing up (the Kinks’ Dedicated Follower of fashion).

British music – as epitomised

also by the Kinks (Dead End Street) – also tapped into different musical traditions

like pub singalongs (Mrs Mills was knocking out two albums a year on EMI at the

time), brass bands (McCartney would later record the Black Dyke Mills Band who

were one of Apple’s first signings), music hall traditions (McCartney's

When I'm 64) and the pastoralism of composers like Delius.

British music – as epitomised

also by the Kinks (Dead End Street) – also tapped into different musical traditions

like pub singalongs (Mrs Mills was knocking out two albums a year on EMI at the

time), brass bands (McCartney would later record the Black Dyke Mills Band who

were one of Apple’s first signings), music hall traditions (McCartney's

When I'm 64) and the pastoralism of composers like Delius.

It's notable there is not one

extended guitar solo on Sgt Pepper but brass and orchestral instruments carry the songs

in many instances. References are to the past (Lennon’s Being for the Benefit

of Mt Kite, it’s lyrics lifted from a 19th circus poster in his home) and the

mundanities of life are also scattered throughout. The people here are often

ordinary: Rita the meter maid, the suburban family in She’s Leaving Home,

McCartney’s passages in A Day in the Life . . .

Lennon’s brittle and urgent

Good Morning: “It’s time for tea and meet the wife” -- widely read as Meet the

Wife, the BBC television sitcom starring Thora Hird – railed against the mundane

also.

That domesticity – from four adults with partners, three of them living outside London in leafy suburbs – is there too

in With a Little Help From My Friends and Lennon’s world weary “I read the news

today/I saw a film today” on A Day in the Life.

That domesticity – from four adults with partners, three of them living outside London in leafy suburbs – is there too

in With a Little Help From My Friends and Lennon’s world weary “I read the news

today/I saw a film today” on A Day in the Life.

But all of these images and

references were also within the same musical and emotional space as Lennon’s LSD-infused escapism of Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds and its

child-like delivery, and Harrison’s spiritually-inclined Within You Without You

with an Indian ensemble, the latter closing with laughter Harrison insisted be

there to undercut its philosophical earnestness.

Where American hippies took

the counterculture seriously as an alternative lifestyle (giving rise to “the

Woodstock Nation”) in Britain it was looked upon with scepticism and the dressing-up

as a bit of silly out-of-school fun

That parallel mood however --

where Indian and esoteric philosophies plus consciousness-altering drugs like

LSD converged -- was epitomised best by Harrison in It’s All Too Much, written

at the time of Sgt Pepper’s but not released until two years later: “Show me

that I’m everywhere and get me home for tea”.

More domesticity.

In Britain there were

boutiques with names like I Was Kaiser Bill’s Batman and Granny Takes a Trip,

groups such as the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, clothing designers The Fool and whimsical singles like Winchester

Cathedral by the New Vaudeville Band (which replicated the Rudy Vallee

megaphone technique from the Thirties).

All this – and Sgt Pepper -- would

soon enough launch Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

To paraphrase Sir Winston

Churchill, Britain and America were two nations divided by a common music.

If the USA had become the

world of quick resolution sitcoms (My Three Sons), in Britain there were still kitchen-sink dramas and

Coronation Street.

Sgt Pepper arrived in in the

year that sales from albums outstripped those of singles . . . and the schism

between the two was a chasm: the UK singles charts were littered with MOR

artists like Harry Seacombe, the Seekers, Sandy Shaw, Petula Clark and Tom

Jones.

Sgt Pepper arrived in in the

year that sales from albums outstripped those of singles . . . and the schism

between the two was a chasm: the UK singles charts were littered with MOR

artists like Harry Seacombe, the Seekers, Sandy Shaw, Petula Clark and Tom

Jones.

Singles still counted – the

best sellers of the year included, of course, Strawberry Fields Forever/Penny

Lane although it came in at 24 well behind the top two by Englebert Humperdinck

who had three of the top five, and Procol Harum's dreamy psychedelic hit A

Whiter Shade of Pale at number four.

But albums were where the

innovations were being made, and Sgt Pepper changed the landscape.

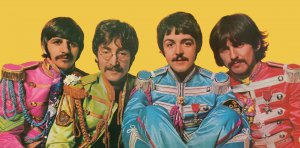

Long before David Bowie’s musical

and sartorial ch-ch-changes and Madonna’s ever-changing personae and images,

the Beatles offered a calculated and quite remarkable reinvention with Pepper. It

started on that iconic cover – where their colourful new selves and former Fab Four/mop

tops stand side-by-side apparently around a grave bearing their name.

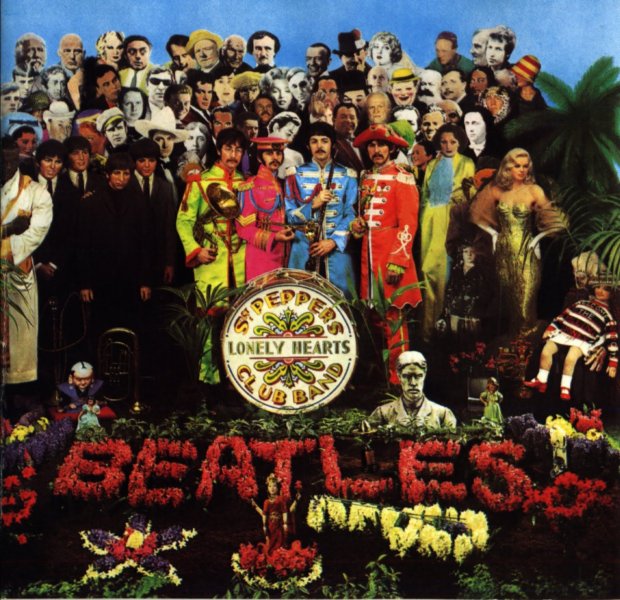

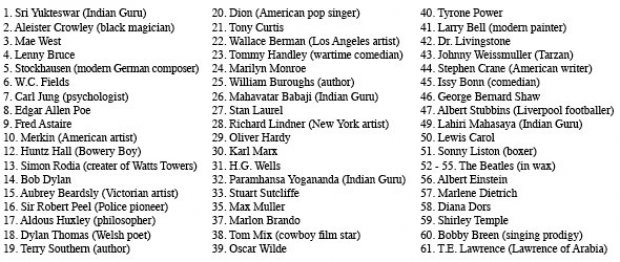

And who were all these people on the cover? Were they fellow mourners,

there to witness the Beatles’ resurrection, ghosts or influences from the

Beatles’ past or simply just a gaggle of random onlookers? [See answer below]

In the end it hardly mattered.

These days music arrives via

computers and phones without visual or tactile reference points, but Pepper came

from a very different age, a time when people read the printed lyrics (Pepper’s

the first rock album to print them on the cover) and cover photos were poured

over for clues and signs.

These days music arrives via

computers and phones without visual or tactile reference points, but Pepper came

from a very different age, a time when people read the printed lyrics (Pepper’s

the first rock album to print them on the cover) and cover photos were poured

over for clues and signs.

And Sgt Pepper supplied them in

abundance.

In years to come it would

feed the “Paul is dead” conspiracy.

From the album’s title and

lyrics (“We’re Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band”) to the diverse and complex

music within, the album reset the parameters of what was possible within

popular music. This was LSD-influenced music presented as a kaleidoscope of

colours, imagery, characters and complex studio production.

Even for the most cynical Beatles

naysayers – and there seem to be a few who prefer to take their "controversial" position rather than address the artifact -- this is extraordinary music from the most creative collection of

pop-rock individuals.

In that Time article George

Harrison said, “We haven’t really started yet. We’ve only just discovered what

we can do as musicians, what thresholds we can cross.

“The future stretches out

beyond our imagination.”

“The future stretches out

beyond our imagination.”

But in the end that didn’t happen.

Within a few months their manager Brian Epstein was dead and the

rudderless Beatles – guided by McCartney – embarked on their Magical Myster

Tour folly, and for the first time they became figures of widespread derision.

Gibb is right in many ways:

Even the Beatles immediately subsequent single All You Need is Love found them

echoing the mood of the era – now long gone -- rather than leading from the

front as they’d done previously.

Gibb is right in many ways:

Even the Beatles immediately subsequent single All You Need is Love found them

echoing the mood of the era – now long gone -- rather than leading from the

front as they’d done previously.

They meditated, turned down the drug intake and a year later were three individual songwriters competing for space.

But even at the height of this psychedelic triumph it is easy to fall for the Gibb cliche that the Beatles' music at this time was all ethereal and dream-state acid music. Sgt Pepper also included Lennon's biting rock of Good Morning Good Morning (which sounds so much sharper and acerbic in the new mix) and the soul-influences on McCartney's Getting Better (with soul-baring lines which seem to have come from Lennon) alongside McCartney's music hall and ballad offerings.

Sgt Pepper's was a more complex and diverse collection of songs than perhaps memory and distance allow.

And the psychedelic style was one they rarely revisited, aside from moments of Magical Mystery Tour, Lennon’s brilliant I Am The Walrus and perhaps bits of Abbey Road (McCartney’s Maxwell’s Silver Hammer).

Their Beatles double of ’68 – aka The White Album -- the songs often stripped back -- sounded like the work of individuals and not a group at all.

It was left to others –

notably Electric Light Orchestra in their immediate wake – to pick up the mantle of pop embellished by

strings and brass.

In retrospect, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band opened a window onto

a kaleidosscope world painted in a colourful way where the mind could go wandering

. . .

But for the Beatles, they just as quickly closed it.

That double album 17 months later, from a very different Beatles, came

in a plain white cover.

The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is reissued by Universal Music as a single CD, double CD, double vinyl, and a box set of four CDs with a DVD, a booklet and memorablia.

Fred - May 26, 2017

Six discs ... and no 'inner groove'!

Savepost a comment