Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Big Boys

And that he actually surpassed the King when it came to consolidating and embedding this exciting music in popular culture.

As with Presley, Berry forged an amalgam of white country music and black rhythm and blues (his first hit Maybellene was an adaptation of the Western Swing song Ida Red) but while Elvis retreated into ballads and generic rock'n'roll covers, Berry was writing original songs which celebrated this new music and its teenage audience.

Maybellene, recorded in Chicago, May 1955

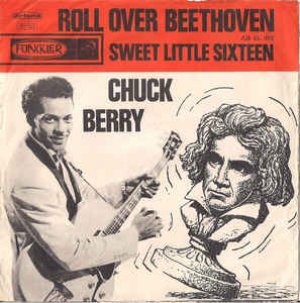

He celebrated the liberating power of this new genre in songs like School Days (“hail, hail rock'n'roll, deliver me from the days of old”) and Roll Over Beethoven (“and dig these rhythm'n'blues”), a song which also cleverly saluted the power of the radio DJ.

And

of course he wrote Rock and Roll Music (“got to be rock'n'roll

music, if you want to dance with me”).

And

of course he wrote Rock and Roll Music (“got to be rock'n'roll

music, if you want to dance with me”).

"just let me hear that rock and roll music, it's got a backbeat you can't lose it"

Rock and Roll Music, recorded Chicago, May 1957

Chuck Berry astutely recognised the emerging youth demographic and wrote songs specifically for and about these kids: he sang of cars, high school, the dance and dating.

"Hail hail rock'n'roll, deliver me from the days of old" -- in School Day

School Day, recorded Chicago, Dec 1956

and he celebrated car culture

You Can't Catch Me, recorded Chicago, Dec 1955

He sang of a pop-obsessed teenager in Sweet Little Sixteen (“she's just got have about a half a million framed autographs”).

Sweet Little Sixteen, recorded Chicago, Feb 1958

With only one notable exception – his godawful '72 hit My Ding-A-Ling – nearly all of Chuck Berry's best known songs came in a rush on the Chess label in a five year period from August '55 when he released Maybellene.

He was prolific, his three albums between May '57 and July '59 were stacked with rock'n'roll classics. In the early Sixties, after his hits stopped coming, Berry's classic songs were adopted as the template and training ground for groups in Manchester, Liverpool, London and beyond around Britain, and in America from the Jersey Shore to Gainesville in Florida and across to the West Coast.

The young Brian Wilson adapted a Berry song for Surfin' USA and Bob Dylan has acknowledged that Subterranean Homesick Blues was inspired by Berry's talk-sing Too Much Monkey Business.

Berry

also celebrated American consumer culture in the Fifties (Back in the

USA) and himself (Brown Eyed Handsome Man), and his songs became

central to any subsequent film set in the rock'n'roll era (American

Graffiti, Back to the Future etc)

Berry

also celebrated American consumer culture in the Fifties (Back in the

USA) and himself (Brown Eyed Handsome Man), and his songs became

central to any subsequent film set in the rock'n'roll era (American

Graffiti, Back to the Future etc)

Johnny B Goode, recorded Chicago Feb 1958

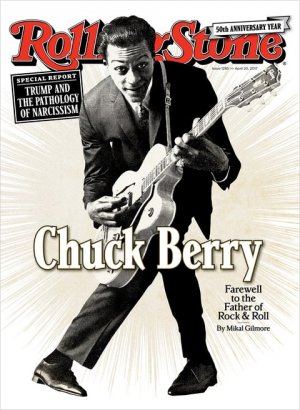

And as black man playing for white audiences on national television Chuck Berry eroded the barriers of race in a way that Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Buddy Holly could never do.

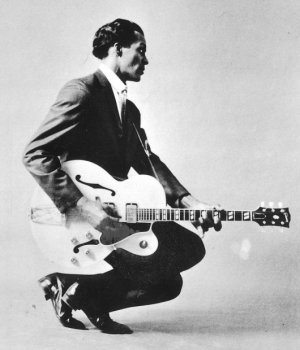

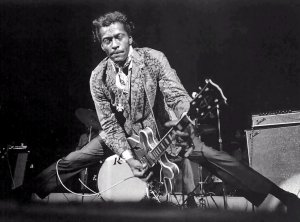

He also brought the portable electric guitar to the forefront of rock'n'roll – guitars becoming increasingly cheaper – and that freed him up to do the duck walk, sling his instrument down like a phallic extension of his body and be a stage-prowling entertainer.

He was distinctive.

In his performances, because he'd learned how to keep a crowd's attention in small clubs, Berry epitomised the new style of spotlight grabbing, shape-throwing entertainment.

He

was talented, good-looking, smart, witty and wrote memorable,

wonderful songs driven by a backbeat and that precise and steely

guitar sound.

He

was talented, good-looking, smart, witty and wrote memorable,

wonderful songs driven by a backbeat and that precise and steely

guitar sound.

Then there was Chuck Berry the man . . . and that was always more problematic.

He was educated, literate, loved words (Shakespeare a favourite), older than his rock'n'roll peers – almost 30 when he had his first hit – and came from a large family of smart, good looking and equally ambitious siblings.

He

often spoke with an almost exaggerated and aristocratically British

accent.

He

often spoke with an almost exaggerated and aristocratically British

accent.

But he was also suspicious, secretive, indifferent to others, obsessed with money, had a peculiarly distasteful sexual obsession.

You can look up coprophilia and that shocking story.

He was also troublesome and arrogant.

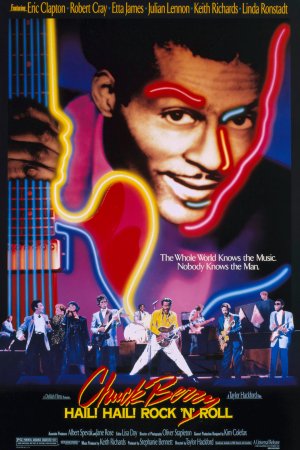

Just check him in the film Hail! Hail! Rock and Roll and see how he behaves towards Keith Richards who is trying to celebrate his hero.

But stick around for the closing credits.

There a rather different Chuck Berry from the rock'n'roller we know plays a solo, sensitive version of the old ballad House for Sale.

He was acutely sensitive to race as he saw black artists being exploited and not getting their rightful dues.

Although he relied on pianist Jonnie Johnson in the studio whose ban he had joined and took over (and who never got the credit he deserved for helping shape Berry's songs), when he went out on the road it was just him and his guitar case, playing with local pick-up bands he rarely spoke to, the cash money in a bag and then on to the next show without so much as a howdy-do.

That was his life both before he went to jail in the early Sixties (when bands in the British Invasion saluted him) and for decades after his release: same songs night after night.

But they were the best songs.

When he died some obituary writers said it was a pity that for a later generation Berry would be remembered for his chart-topping but slight My Ding-A-Ling in the early Seventies which was loaded with sexual humour of the most base kind.

But what did Chuck think of that song? He just looked at the royalty cheques, banked them and then went back on the road with his guitar and added it to his set. No big thing.

And it's worth noting that for every great song Chuck Berry wrote there was always another much lesser item in his catalogue.

He was a self-plagiarist who wrote limp Latin and faux Mexican songs (because he liked the styles) and could be sentimental (Memphis, Tennessee).

So when in 2016, at 90, he announced a new album – his first of original material in 38 years – there was as much trepidation as surprise.

He didn't live to see its release and, from his perspective worse, a royalty cheque. Although knowing Chuck's business practices you suspect he got the money up-front. Cash in a brown paper bag most likely.

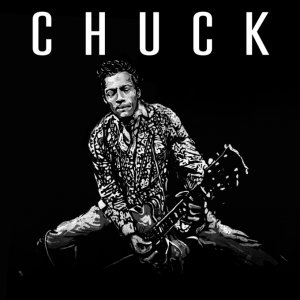

It was

hard to know what to expect from that new 10 song album simply under

the title Chuck. Certainly not “I hope you like my new

direction”.

It was

hard to know what to expect from that new 10 song album simply under

the title Chuck. Certainly not “I hope you like my new

direction”.

But the heart sinks at a title like Lady B Goode (an uncalled for sequel about the woman Johnny left behind) which manages to refer to his own hit and the Gershwins in a breathtaking piece of hubris.

Worse there's a cover of Ray Charles' considerably lesser work ¾ Time (Enchiladas)

By all accounts many of these songs – eight of them originals – date back to the Eighties but you'd have to say something like the obvious Big Boys (generic Berry riffery and the perspective of schoolboy looking at the older kids) might have been in his unreleased songbook from three or four decades ago.

The Chuck album was recorded in various studios around St. Louis and features his longtime backing band which includes some of his children (Charles Berry Jr. on guitar and singer Darlin Ingrid Berry also on harmonica), plus his bassist for four decades Jimmy Marsala, pianist Robert Lohr and drummer Keith Robinson.

These people know Chuck and his music, they supported him for almost 20 years in the Blueberry Hill club.

It also includes guest performances from Gary Clark Jr., Tom Morello and Nathaniel Rateliff (on Big Boys) and Chuck’s grandson Charles Berry III.

Because Berry's guitar playing was so distinctive – and seminal – it's no surprise that he pulls it out here (you'd be disappointed if he didn't) but then even when he hands to job to others they seem to just shadow his former self.

But what else could we expect?

There's a reflective, sentimental ballad Darlin' with Ingrid (“the time is passing fast away, there's been many sundowns that I've seen”), the faux-Caribbean Jamaica Moon and a lame ballad (You Go to My Head).

That Enchilada song – recorded live – is certainly the equal My Ding-A-Ling at the very bottom of the tall totem pole of Chuck Berry best recordings.

It's

a weak cover on an album which comes with a framable photo on the vinyl version. Probably the best thing about it.

It's

a weak cover on an album which comes with a framable photo on the vinyl version. Probably the best thing about it.

Aside from Big Boys (and you'd like to have heard Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty or some other fan turn it into the classic rocker it deserves to be . . . but that won't happen) the highpoint is an unexpected, almost spoken-word piece The Dutchman.

It's a low, bluesy thing – as is Eyes of Man which follows – and a story which sounds conceived in the similar spirit of Tom Waits in his Heart of Saturday Night/Small Change period.

Given his facility with words, you wonder why Chuck Berry didn't do more like this.

He probably figured there was no money in it.

Chuck Berry was one of the greatest entertainers of the 20th century and many, many of his songs from the Fifties are classics. They are joyous, fun, frequently astute, clever and tell us more about the era than most of the songs of his peers.

Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis frequently dealt in slogans, Chuck Berry told stories.

His best songs have endured the decades and even transcend them, and even right now there are guitarists learning his riffs.

His legacy will endure long after this career coda which, while it doesn't demolish the legend, rarely adds anything to it.

post a comment