Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Jungle

In a brief prologue to his hilarious and fictionalised war memoir Adolf Hitler, My Part in His Downfall, Spike Milligan made reference to his previous book Puckoon.

He wrote, “After Puckoon I swore I'd never write another novel. This is it . . .”

A few years ago on the release of the Jimi Hendrix album People, Hell and Angels, longtime Hendrix engineer and reissue man Eddie Kramer told Elsewhere – and everyone else – that the well was now dry and there would not be another such Hendrix studio album of previously unavailable material.

Both Sides of the Sky, just released, is it.

Curiously enough, despite those denials of any more decent and previously unreleased studio recordings, everyone writing about Both Sides of the Sky is following the liner notes to the album by John McDermott and comfortably referring to it as the final part of a trilogy which opened with Valleys of Neptune (2010) and People Hell and Angels (2013).

Okay then.

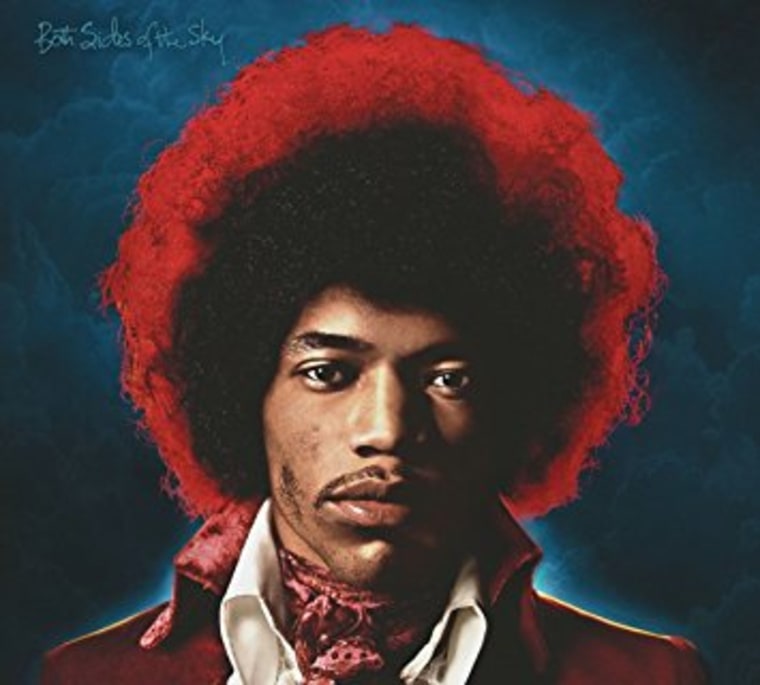

So let us accept it for what it is, a

handsomely packaged album (CD and vinyl) with liner notes, great

photos (the airbrushed cover will be down to taste but the live shots

in the booklet are excellent) and 13 previously unreleased studio

recordings, among them a piece which was used on the Scorsese

Presents the Blues television series but never released (Georgia

Blues) and of course different studio takes of material that Hendrix

frequently went back to and found a new way into (Hear My Train A

Comin', Stepping Stone).

So let us accept it for what it is, a

handsomely packaged album (CD and vinyl) with liner notes, great

photos (the airbrushed cover will be down to taste but the live shots

in the booklet are excellent) and 13 previously unreleased studio

recordings, among them a piece which was used on the Scorsese

Presents the Blues television series but never released (Georgia

Blues) and of course different studio takes of material that Hendrix

frequently went back to and found a new way into (Hear My Train A

Comin', Stepping Stone).

Hendrix aficionados have long speculated on where the musician might have been heading before his death at 27 in September 1970, but that matter was largely resolved by the reconstructed final album First Rays of a New Rising Sun ('97) and the scatterings of various sessions in his final years – as these here are, most from '69 and early '70, two from '68 – are inconclusive.

Sessions with Miles Davis and improbably, the French chanson singer/poet Leo Ferre, never happened.

But here we have one of the final sessions with the original Experience of Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell (Hear My Train), a number of sessions with the incoming team of Buddy Miles and Billy Cox, a track with emerging blues guitarist Johnny Winter and drummer Dallas Taylor who would soon join Crosby Stills and Nash (Things I Used to Do), and a take on Joni Mitchell's Woodstock with Stephen Stills (who would carry the song over the CSN) and Buddy Miles.

Stills also appears on $20 Fine (vocals and organ) alongside Mitchell and pianist Duane Hutchings and the cut of Georgia Blues is with singer/saxophonist Lonnie Youngblood, drummer Jimmy Mayes, bassist Hank Anderson and organ player John Winfield.

The final piece Cherokee Mist has Hendrix on guitar and electric sitar with just drummer Mitchell.

Elsewhere Hendrix plays vibes (on Sweet Angel).

And just through that revolving door

cast alone you can see how this collection is going to be somewhat

hit and miss.

And just through that revolving door

cast alone you can see how this collection is going to be somewhat

hit and miss.

Muddy Waters' Mannish Boy with Cox and Miles which opens is a brittle piece that is more funk-pop than the blues of its origins, vocally Hendrix sounds uncommitted and there is barely a guitar solo in its five minutes.

It's an unpromising opener and after the familiar Lover Man (another stab at it with Cox and Miles, other versions have appeared on numerous live albums like Stages, Isle of Wight, Woodstock and Fillmore East as well as a studio version with the Experience on Valleys of Neptune) it isn't until Hear My Train A Comin' – another fairly hoary familiar – that things ignite.

With the original Experience, this seven and half minute treatment from early '69 is the Hendrix that fans come to the posthumous albums for: furious and shapeshifting guitar work, powerful dynamics from the barest of tickles to chopping that mountain down with the side of his hand. Unlike Mannish Boy he keeps this close to incendiary psychedelic blues. It's thrilling, especially if Hendrix up until Band of Gypsys is your thing.

Band of Gypsys – with Cox and Miles -- marked a break with many aspects of his past and a move into soul and funk rather than psychedelic rock, and that is evident here in Power of Soul which would become one of that band's cornerstone pieces. It feels transitional between the two styles but is a powerful marriage of both.

Stepping Stone is taken at a furious clip but is a short studio version of the kind which are all over the posthumous albums. Exciting for its duration but – aside from guitar pyrotechnics in the final third and Cox's pumping bass – not a high point.

The two tracks with Stills on vocals are also interesting enough but again hardly essential: $20 Fine is largely unmemorable, the strident Woodstock the better of the two for never having been heard before, Miles' assertive drumming and Hendrix playing bass.

Of much more interest are the work in progress Send My Love to Linda which – although with Cox and Miles – might have been conceived around the Axis period and fitted on that album, and the more experimental and seven minute improvised sonic landscape of Cherokee Mist which alludes to his Native American heritage in Mitchell's drum pattern and overdubs wailing guitar behind his simple sitar playing.

Again neither are essential Hendrix but show how much he was searching for different directions.

The three and half minute Jungle with just Miles is little more than a quiet studio improv (kinda pretty though and edging towards brooding funk) as is Sweet Angel with drummer Mitchell and Hendrix on guitar, bass and vibes. It is the working drawing for what became the more refined Angel.

The blues jam with Winter on Guitar Slim's Things I Used to Do is exactly that and little more, but Georgia Blues is more satisfying as the band with Youngblood's tough tenor sax stretch out on the kind of groove and changes they knew intuitively. You'd be baying like a hound dog if you heard it live in a Southern club.

So there it is, almost half a century

after his death yet another new album of Jimi Hendrix in the studio.

So there it is, almost half a century

after his death yet another new album of Jimi Hendrix in the studio.

Given the various provenances of its material Both Sides of the Sky is uneven as you might expect, but for hardcore fans who have been through the various missteps, sidesteps and giant leaps in Hendrix's extensive catalogue of posthumous releases – I have about 30 and know of people with many times that – there are always going to be nuggets to be chivvied out.

If that's it for his studio recordings, and again Eddie Kramer says it is but also speaks of albums of previously unheard live material to come, then we can put a fullstop here.

Or perhaps, more appropriately, an ellipsis . . . .

As you might have guessed, there is a considerable amount of Jimi Hendrix at Elsewhere starting here.

post a comment