Graham Reid | | 8 min read

No Expectations

Half a century ago the Rolling Stones released their Beggar's Banquet album, widely considered a return-to-form after the debacle of their shapeless attempt at psychedelia on the largely unlistenable Their Satanic Majesties Request of December 1967, released some six months after the Beatles' Sgt Peppers.

In a cover which referred to Pepper's glowing hippie-era colours, Satanic Majesties would be a low point for the Stones. It's 50th anniversary came and went last year, and despite a mono and stereo re-presentation on double vinyl in a box set it garnered few reconsiderations . . . and none acclaiming it as an overlooked and unfairly dismissed masterpiece.

It was proof that you needed musical ideas, not drugs and self-belief, when you went into a studio.

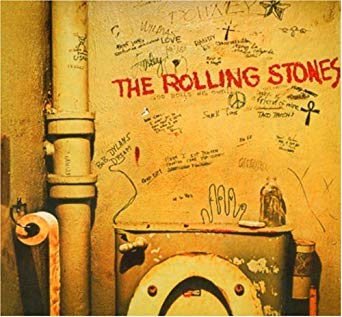

Beggar's Banquet arrived exactly a year later having been delayed by three months after their original “toilet” cover art was rejected by their record company.

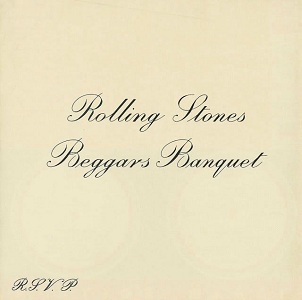

Unhappily for the Stones, who finally relented and went for another cover, it came out a few weeks after the Beatles' “White Album” and again – because of Beggar's Banquet's plain white “invitation” cover – it engendered, unfairly this time, a Beatles-copy comparison.

Unhappily for the Stones, who finally relented and went for another cover, it came out a few weeks after the Beatles' “White Album” and again – because of Beggar's Banquet's plain white “invitation” cover – it engendered, unfairly this time, a Beatles-copy comparison.

But Beggar's Banquet was immediately hailed as a focused and coherent work (unlike the scattershot White Album), and considered then, and now, to be the band getting back to the business of raw rhythm'n'blues which had been their first platform.

To some extent that is true: songs like the salacious Parachute Woman and the sleazy sexuality of Stray Cat Blues were pure r'n'b. No Expectations is an acoustic blues like a late 20thcentury take on Robert Johnson with sublime slide from Brian Jones enhancing its pathos. It was Jones' last serious contribution to the band he founded as drugs and self-doubt plagued him, and the Jagger-Richards team took control of the band's direction.

But the album is more complex than simply a look back to their origins as a rock'n'roll blues band (they were never pure blues revivalists like the Mayall cabal which sought authenticity). There were other dimensions and ambiguities on Beggar's Banquet which reward even today.

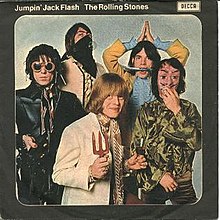

Some six months previous the Stones had signaled their return to a more visceral blues rock (“violent” in the words of Rolling Stone magazine's Jon Landau) with the devil-conjuring Jumpin' Jack Flash. It was recorded in the same sessions which birthed Beggar's Banquet and despite Jones' presence on guitars, the song was proof of just how the pendulum had now swung completely to the Jagger-Richards team . . . with pianist Nicky Hopkins.

Some six months previous the Stones had signaled their return to a more visceral blues rock (“violent” in the words of Rolling Stone magazine's Jon Landau) with the devil-conjuring Jumpin' Jack Flash. It was recorded in the same sessions which birthed Beggar's Banquet and despite Jones' presence on guitars, the song was proof of just how the pendulum had now swung completely to the Jagger-Richards team . . . with pianist Nicky Hopkins.

It was a new kind of old blues: “I was born in a crossfire hurricane” was an idea as ancient as time in the blues, but for Richards it was contemporary, the period of his birth during the Second World War. This was a different and very British rock'n'roll blues. And up front Jagger strutted the part.

It signaled what was to come on Beggar's Banquet and as it stretched them musically some of those echoes would appear Beggar's Banquet songs like Stray Cat Blues, Sympathy for the Devil and Salt of the Earth.

As Simon Frith wrote about Beggar's Banquet, “I've had the Rolling Stones' Beggar's Banquet ten years already and it still makes me laugh. It's the cleverest record the Stones ever made and the subtlest, and it includes all the usual arrogance, dance and dirt.

“I don't know how Mick Jagger became the symbol of rock and roll but he did and I've had to think about him and his band and his music more than I've had to think about anything else in rock.”

And he was writing in the late Seventies, after Exile on Main Street.

For its 50th anniversary Beggar's Banquet gets a remastered vinyl re-presentation with a single of Street Fighting Man (in mono) and a limited edition bonus seven-inch flexi-disc (!) of an interview at the time between Mick Jagger and someone in their Japanese record company. There is a CD version available (not being released in New Zealand but you can get it through https://store.digitals.co.uk), it also will be available digitally and the vinyl edition (in a gatefold sleeve as per the original) comes with a download for the album and the interview.

The original cover is also restored to its rightful place with the "invitation" sleeve as an overwrap. This anniversary edition will be released on November 16.

If The Last Time in '65 was the single which really announced the Stones as songwriting and pop-rock contenders and Satisfaction later that year created the fault-line between pop and rock, Beggar's Banquet was their first fully formed rock album . . . with its roots in more than just r'n'b and blues of the old style.

If The Last Time in '65 was the single which really announced the Stones as songwriting and pop-rock contenders and Satisfaction later that year created the fault-line between pop and rock, Beggar's Banquet was their first fully formed rock album . . . with its roots in more than just r'n'b and blues of the old style.

Now, with this album, they were distinctive and themselves.

At the same time as they were going back to what they knew (blues, rhythm'n'blues) they also started to explore other music with deep roots in America (country on the deliberately hokey Dear Doctor, folk blues on Prodigal Son by Mississippi-born Robert Wilkins) as well as British/Celtic folk (Factory Girl).

Just as U2 would clumsily do on Rattle and Hum two decades later, the Stones – Jagger and Richards with pianist Nicky Hopkins – recognised there was a bigger past out there to be mined for ideas and as platforms to stand on.

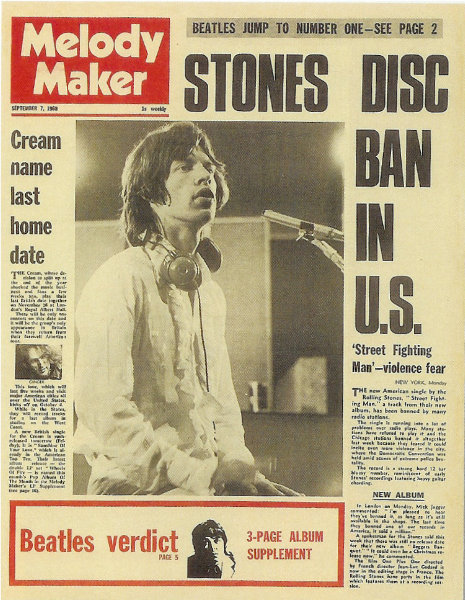

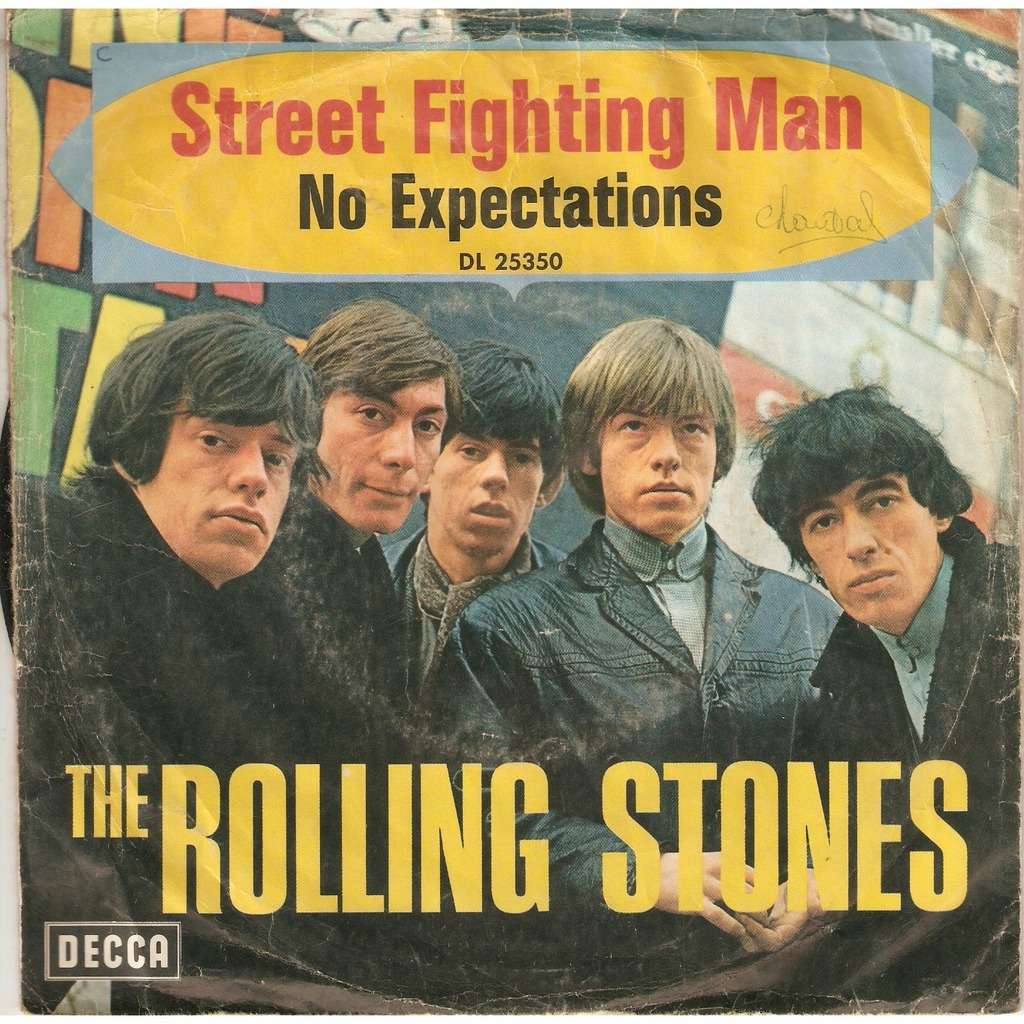

The only single off Beggar's Banquet, Street Fighting Man – inspired by the riots in Paris and London, and given extra texture by Jones' sitar and tambura drone – certainly captured the angry zeitgeist of '68 . . . and yet?

Jagger might have said “the time is right for fighting in the street” (adapting "the time is right for dancing in the street" on Dancing in the Street by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas) but he also begged off actually getting out there and doing anything: "What can a poor boy do but sing in a rock'n'roll band . . ."

At the time this was a cop-out equal to Lennon on Revolution (“Don't you know you can count me out/in” on Revolution #2 on The White Album)

The music of SFMan – as with the bristling and violently angry distorted sound of Revolution when it appeared on the flipside of the more benign Hey Jude -- sounds more politically engaged than the singer is.

Jagger went to an anti-Vietnam war demonstration in London's Grosvenor Square in his Bentley, marched for a bit, got his photo taken then got back in the Bentley driven by a chauffeur and went off again.

The phrase "radical chic" was invented for just such a chic/hip appearance of radicalism in '68.

Jagger was always a bob-each-way kinda guy.

Jagger was always a bob-each-way kinda guy.

As Richards once observed, “Mick is an interesting bunch of guys”

That ambiguity is all over Beggar's Banquet.

The Anglo-folk of Salt of the Earth seems to sympathise with the working class but then: “When I search a faceless crowd, a swirling mass of grey and black and white, they don't look real to me, in fact, they look so strange . . .”

By the end of the song -- and no amount of uplift from the Watts Gospel Choir and Hopkins' hammeringly soulful piano can ameliorate this – the Stones came off in that violent year when colours were nailed high on mast as ambivalent if not completely disengaged.

Jagger – middle-class and for a while a student at the London School of Economics – was playing a part, as he would increasingly do.

Despite his mock Cockey accent -- mockney -- he actually spoke very well. An interesting bunch of guys were inside him.

Despite his mock Cockey accent -- mockney -- he actually spoke very well. An interesting bunch of guys were inside him.

As with other songs on the album you are left in doubt about what side (if any) these people are on. Not that musicians need to take sides . . . but in '68 (as Lennon was weakly acknowledging) people in that revolutionary year most definitely were.

Are you in or are you out?

The Stones sounded in, but were actually out.

Factory Girl with Rick Grech on fiddle, is superficially a more convincing celebration of the working class, but the way Jagger sings it – all Dylan drawl in places – undercuts any sense of seriousness. It's a throwaway but leavens what else is going on across the album.

On Jigsaw Puzzle the spirit of Dylan (circa Blonde on Blonde) takes hold of Jagger with its series of characters and caricatures: “There's a tramp sitting on my doorstep trying to waste his time, with his mentholated sandwich he's a walking clothes line . . .” and later there is the Bishop's daughter, the gangster, the band members (on some level the song is a kind of band autobiography), 20,000 grandmas waving their hankies in the air and the Queen bravely shouting “What the hell is going on?”

It may be Dylanesque – it's also six minutes long – but Richards' slide playing (Jones added mellotron) elevates it and it builds in the same manner as Salt of the Earth. It was a fine closer to side one, just as Salt of the Earth closed side two on such an anthemic moment.

The album's sexual content was explicit (Parachute Woman, Stray Cat Blues) but never quite as repellent as the earlier Under My Thumb.

The songs on Beggar's Banquet all have roots somewhere and as Landau notes in his assessment at the time, “The Rolling Stones are constantly changing but beneath the changes they remain the most formal of rock bands. Their successive releases have been continuous extensions of their approach, not radical redefinitions, as so often has been the case with the Beatles.

“The Stones are constantly being reborn, but somehow the baby always looks like its parents.”

So yes, in some measure Beggar's Banquet was a return to roots, but only to expand on them, to follow other roots and routes. They hadn't done much like Dear Doctor or Salt of the Earth (musically) before . . . nor had they explored that Afro-Cuban percussion style on Sympathy for the Devil.

So yes, in some measure Beggar's Banquet was a return to roots, but only to expand on them, to follow other roots and routes. They hadn't done much like Dear Doctor or Salt of the Earth (musically) before . . . nor had they explored that Afro-Cuban percussion style on Sympathy for the Devil.

Most critics have concluded the album didn't stand for anything but gave the impression that it did . . . but what it did was open up the Stones' musical boundaries and they would from then on be able to explore black blues and r'n'b and gospel and even a bit of soul alongside white music like country and folk, and all of these forms had a deep well of ideas, imagery and musical history to draw on.

Later they would adopt reggae and New York dance too, again looking for new inspirations.

Beggar's Banquet was a watershed album for them and got them back on track, left their founder Brian Jones in their aggressive wake and -- even if it did put them offside with the political radicals at the time – it gave them a platform which would lead to the similarly conceived Let It Bleed (Let It Be as Lennon mused cynically), the almost aberrant and dirty genius of Exile on Main Street in '72 . . . and of course the anthemic and reductive It's Only Rock'n'Roll (But I Like It) just five short years after Beggar's Banquet.

After that it was all more of the same but (aside from Some Girls) often less so.

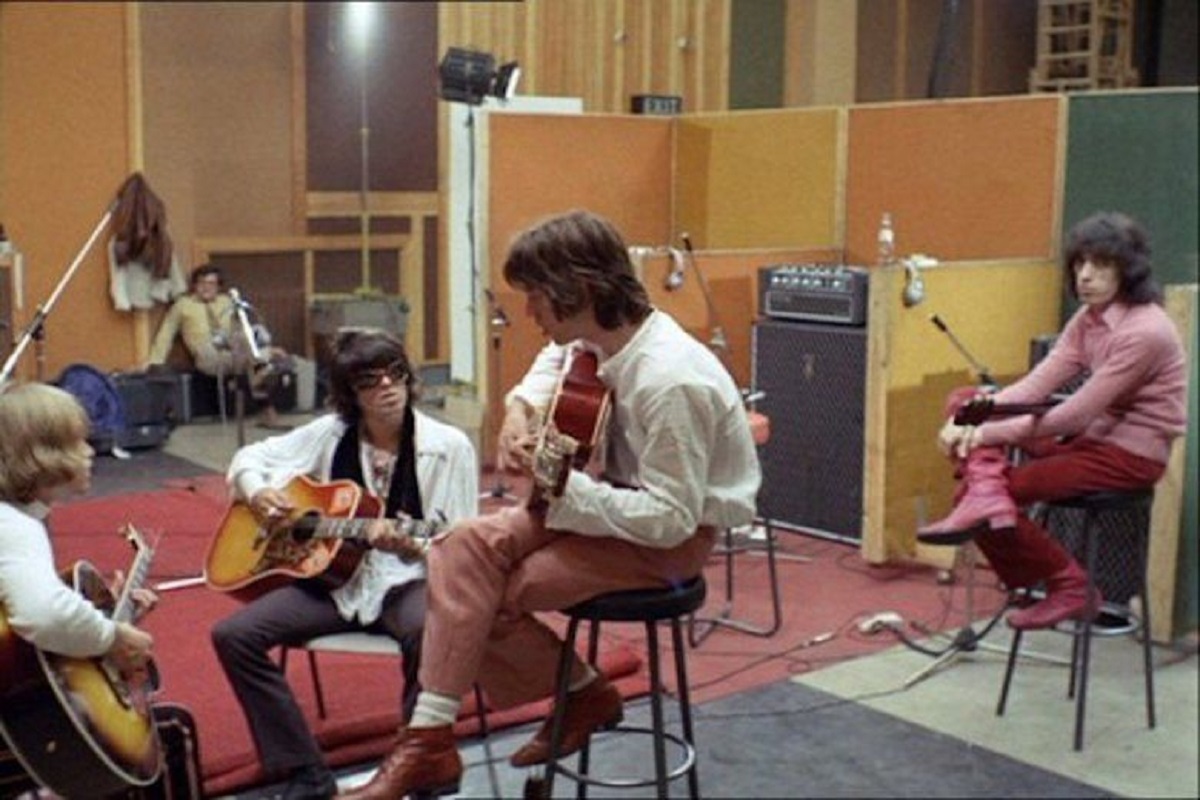

In many ways Beggar's Banquet – brilliantly captured by Jimmy Miller in London's Olympic Studios – was a new beginning . . . but one which had within it the Stones' endgame.

For more on the Rolling Stones at Elsewhere start here.

.

Elsewhere occasionally revisits albums -- classics sometimes, but more often oddities or overlooked albums by major artists -- and you can find a number of them starting here

Graham - Oct 9, 2018

Can't wait for your review of the expanded release of the 'scattershot White Album' !

SaveGlimmerTwin - Oct 18, 2018

It's unfortunate the ABKCO/GlimmerTwins feud hasnt been resolved enough to make this truly a box set worth waiting for. Then again the Stones celebration/reissues have always been in the shadow of Apple anyway - suspect Jagger is always reluctant. He continues to have a laugh it seems in the here & now anyway (always remember his "the jokes on you" comment at the Grammies in the 80's

Savepost a comment