Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Tiligiligi (Medley)

To hear 84-year old Horst Stunzner tell it, the recording session in 1964 took place somewhere just off Queen St in Auckland. The group was in and out quickly, he expected there might be a single come of it and as far as he remembers little if any money changed hands.

“Rudolf and Hugo might have signed something,” he recalls, “but the rest of us never saw any contract, and we were surprised that it came out as an LP.

“They said we were going to cut a record . . . but when it came out as a record . . . I thought it might have been on tape or something.”

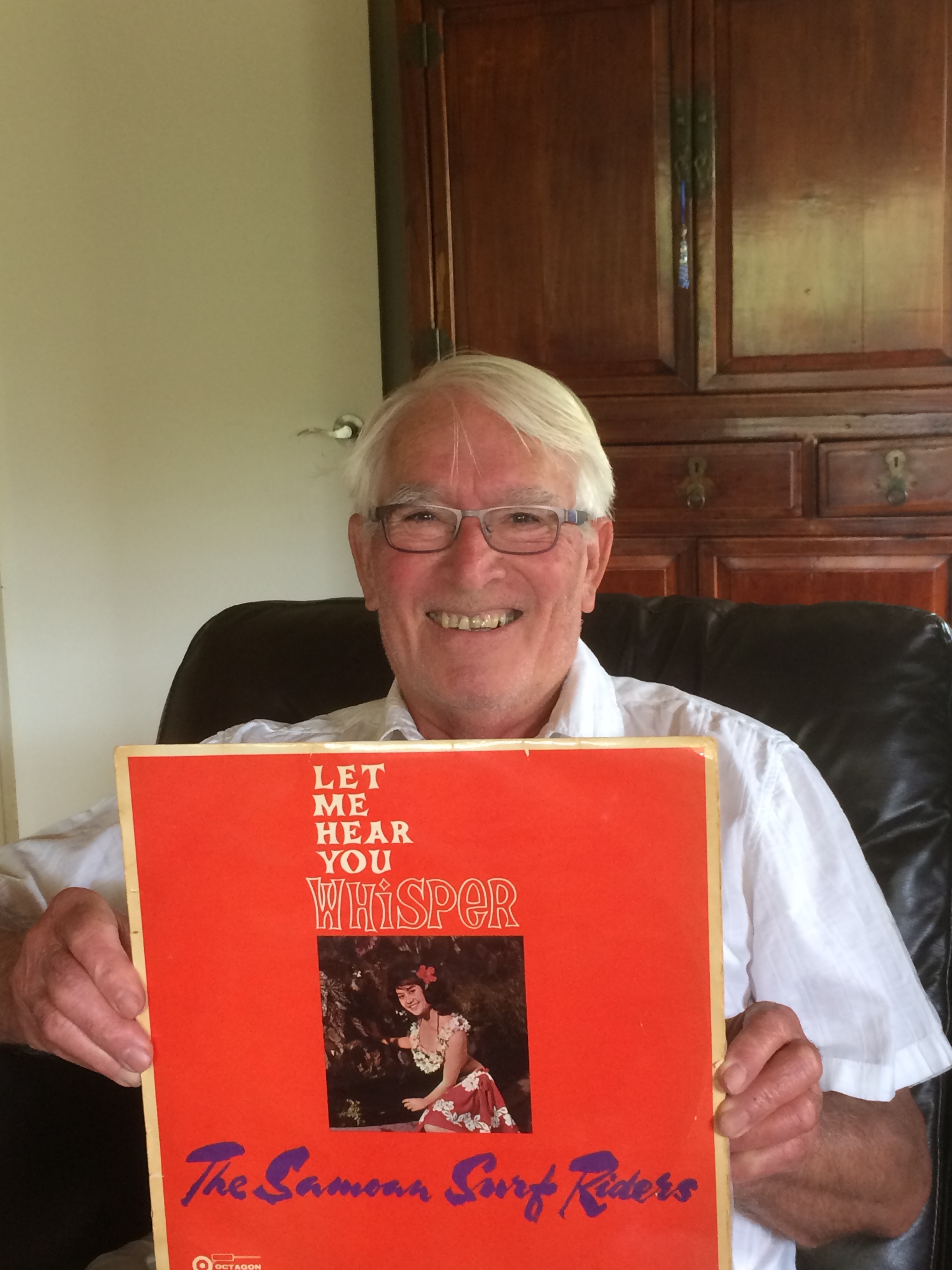

But that album on the Octagon label distributed by Viking, was Let Me Hear You Whisper by the Samoan Surf Riders.

“No, we weren't surfers,” he laughs. “In Samoa we went out to the reef a bit but we were never surfers.”

But there it was, an unexpected album by the Samoan Surf Riders in which the band had very little say other than playing the session. The members were not even named on the cover -- although the engineer Bruce Barton and cover photographer Allen Fox were.

“We had no input, I don't even know who the girl is on the cover. I don't think they sold many copies but eventually it went to Samoa. I think when it first came out I might have got five pounds but they just went into record shops.”

The album didn't disappear – today it can be heard on Spotify and You Tube, and the master tapes are in the Alexander Turnbull Library – but the story behind this collection of traditional songs is just as interesting as the music.

Done in a day (like the Beatles' first album around that time) by a group of non-surfing Surf Riders (shades of the non-surfing Beach Boys) and wrapped in a cover which offers few clues?

Horst Stunzner was born to a German-Samoan family on Upolu and grew up in a small village.

“As a young man I was hearing Samoan songs but we spoke German at home. I didn't start school until age six and Samoa was a New Zealand protectorate then so the curriculum was the same as New Zealand. We mostly had New Zealand teachers.

“My knowledge of Samoan I just picked up and when I first went to school I didn't know any English, they had English lessons in school. The Samoan kids had a separate school down the road.”

Stunzner recalls that the anthropologist Derek Freeman, who later went to live in Australia, was his teacher in standard one and he was interested in Samoan culture and music. Horst sang at school assemblies (“God Save the King and hymns”) and gradually “we did sing some of the well known Samoan songs”.

The Second World War changed everything of course.

Just as in the First World War when Horst's grandfather had all his property seized and was imprisoned on Motuihe Island in Auckland's Hauraki Gulf (along with the notorious escapee Count Felix von Luckner), so his father was arrested at the start of the Second World War and was deported to New Zealand leaving his mother Lily alone with five children and nowhere to live.

Overnight, literally, the Samoan family -- for the second time -- lost their possessions, business and land and their father was interned on Somes Island in Wellington Harbour.

“My father had been a Lutheran but [after the war] we became Anglicans. When my father was interned the only one who came around was the Anglican priest and he was great, so we became Anglicans and so we went to the Anglican church and Sunday School, there were a few Samoans there.

“[The Anglican church] has grown a lot now, the Anglicans were the first to start the Boy Scout movement so I became a boy scout. They were in forefront of the youth groups like Cubs, Scouts and Girl Guides.”

In April 1960 Horst arrived in New Zealand, an admittedly naïve young man in his mid Twenties, “fresh off the boat”, as they say. But a very intelligent and intellectually curious young man who had a yen for the sciences.

“I was 25 or 26 when I came to Auckland. I'd started training in the medical laboratory in Apia but you could only go so far and the qualifications weren't recognised, so I applied to come to Greenlane Hospital and I started in the laboratory there.

“Then I went over to Auckland Hospital and qualified there and then joined MedLab.”

He worked as a lab technician in haematology for almost 40 years.

He had been part of an early exodus of friends and family to New Zealand, and almost unwittingly music entered the picture.

“My sister Trude was here and brother Korty was down in Wellington doing an apprenticeship at the government printing office. And Dad's brother Uncle Fritz and Aunty Sylvia were here. David and Trude were married and had built the house in Te Atatu.

“I stayed with them for a couple of months and then I went to the Auckland City Mission hostel in Grey's Avenue, I was there for about nine months when I was at Greenlane.”

He then lived in “the castle” on Castle Drive just off Mountain Rd – a stately mansion still there today – and he met Eddie Eves who was in the Samoan Surf Riders, and Bruce Dawkins.

“The three of us got that place, we had the upstairs front room in the Castle.

“Eddie was always musical and we knew each other in Samoa and he came to New Zealand before I did. We met at the medical laboratory and he was in microbiology.

How the Samoan Surf Riders formed is slightly convoluted.

“There was another group earlier called the Samoan Surf Riders and they were Rudolf Spemann* who played a bit of piano, his brother Hugo Spemann who was a brilliant ukulele player and has since died, I knew them both from childhood. There was Eddie Eves, myself, Mac McKenzie the steel guitarist who was a Kiwi and married to a Samoan girl Luisa, and Rudolph and Hugo's brother-in-law who was the drummer.”

An earlier version of the Samoan Surf Riders had recorded an EP with Bill Sevesi and His Islanders (Aloha Samoa in '62, on Viking) but this iteration was different.

Horst had met and married Sue in '62 and the group just sang and practiced in their Mt Albert flat, and sometimes in other people's places. It was all very informal and just for fun.

But the Spemann's father Wilhelm had a tremendous knowledge of Samoan songs and lived in New Zealand also, so passed the songs on to his sons and the group which had Eddie, Hugo and Horst as singers.

“Wilhelm Spemann and Dad were interned on Somes Island together with quite a lot of the German-Samoans.

“They went back to Samoa and I knew Rudolf and Hugo as kids, then their whole family came here and that's when we met up later on.

“We practiced and practiced and I think it was Rudolf who suggested we make a record, but it just sort of happened. I was surprised when they said we were going to cut a record, but we'd practiced quite a bit.

“It was a small recording studio, we did it in one day, we knew the songs but it was Hugo and Rudolf's father who really knew them. He remembered them from his childhood.

“I didn't know he had such a deep knowledge of Samoan songs, because when we were kids – Rudolf and Hugo too – we all spoke German at home.

“For him to know all those songs really surprised me.”

When he looks at the sole album by the short-lived Samoan Surf Riders – six of the 12 songs credited to Wilhelm Spemann, one to Hugo and the others traditional – Horst Stunzner remembers them well.

“Let Me Hear You Whisper? We knew that, but everybody knows that one in Samoa. Lupe I Le Vao Maoa [My Lost Dove] was a newly written song by Wilhelm, Tiligili [a medley] was well-known too. My Pago Girl was an old song, so was Tasi Ae Lasi [My One and Only].

“Most are love songs.”

Stunzner laughs when asked if the Samoan Surf Riders ever played anywhere.

“No, the group never performed. But Eddie became part of a group with his brother Bedevere and a cousin of the Spemann boys, Bill. They formed the group Trio Samos. They played at coffee bars and various places in Auckland and they won a talent quest and things took off from there.

“I think Mac was probably in Bill Sevesi's band for a while, Hugo might have played at parties but as a musician nothing really.

“You know, it just surprised us when the record came out. Sue and I had [their first daughter] Tanya and we all just went back to work.

“All I can remember of the recording was there was a microphone and we could see the [engineer] behind the glass, but there was nothing special that I can remember. There were no royalties, we just did it out of interest.”

Sue Stunzner points out that the girl on the cover was Dorice Reed. Glamorous for sure, but she wasn't Samoan.

“She was Tahitian!”

And what happened to these Samoan Surf Riders?

“Rudolf lives at Aorere Point in Auckland, Hugo died about two or three years ago, Eddie died last year and Mac died maybe four years ago.

“I don't know what happened to the drummer but his wife died and she was the sister of Rudolf and Hugo.”

And Horst Stunzner?

He has been married to Sue for 55 years, raised three beautiful girls and at age 70 reinvented himself when he and Sue bought an avocado and persimmon orchard outside of Whangarei after he retired from laboratory work.

The Samoan Surf Riders' story is one of a brief moment captured in time but there is a legacy of lovely music from what was then a land more distant from New Zealand than it is today.

The Samoan Surf Riders' story is one of a brief moment captured in time but there is a legacy of lovely music from what was then a land more distant from New Zealand than it is today.

It is an album of young men singing songs of their homeland and, ironically, living in a country which had imprisoned their parents and grandparents.

Some of the songs will be familiar to a younger audience: Lole sang Let Me Hear You Whisper in the Nineties and on Screems from the Old Plantation on King Kapisi's album Savage Thoughts in 2000 there is a sample from the Samoan Surf Riders.

The liner notes on the Samoan Surf Riders album (produced by John Ewan) naturally talk up its contents, but some of it rings true: “The Samoan Surf Riders sing numbers that will never die, numbers that will never bore on repeated playing, but above all numbers that you'll want for your own collection”.

The final line is in Samoa: “Potopoto mai, tatou usu pese fa'atasi ma le au faipese 'Surfriders' Samoa”.

Horst translates: “That mean, 'Let us gather together, we will sing together with the group, the Samoan Surf Riders'.”

* Rudolf Spemann lead Rudy and the Crystal. Glen Moffatt wrote a piece about them at audioculture here.

This article was first published in late 2018. Horst Friedrich Stunzner died in Whangarei on December 6, 2019.

Peggy in America - Oct 23, 2018

Aaaaaah, such a lovely tale. In America, the heartstrings are pulled by one Duke Kahanamoku in this genrè, and the later-known fame that rose out of his name in the more Homogenized sound, culture, OF surf, but also sport. He was the one brought Surfing to Olympic status. But it is a similar tale, and always, wonderful to finally see another side of the coin, and that the same music was indeed, part of the Universal Language, in that same timeframe. Thank ya, as always!

Savepost a comment