Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Someone very famous – who doesn't turn up on a Google search – once quipped “money follows intellect”.

You'd like to think it was more true than it is, but it is certainly verifiable when you see Big Money (usually in the form of advertisers) paying top dollar to use the work of creative people.

(And I don't mean “creatives” in ad agencies, I mean artists, musicians and the like.)

It has been over 30 years since Nike bought the use of the Beatles' Revolution for a commercial and since then the floodgates have opened. Artists don't call it selling out anymore (Neil Young's This Note's For You almost seems quaintly hippie these days) but rather see it as buying in.

For a while there it seemed all Moby did was license his music to advertisements – well over a dozen and counting (every track on his Play album of '99) – and in an era of declining physical sales many artists were glad of a cheque for work already created.

It helped get it to an audience was the argument . . . the same one Yoko Ono used when signing off on Revolution.

Not all use of music in ads or the commercial sphere is bad, of course.

It helps pay those pesky bills for food and rent and power, and sometimes artists can be commissioned for work. in this country former Underdog Murray Grindlay and the late jazz composer Murray McNabb made their living doing ads, which allowed them to do other things as well. And they are far from alone in that.

When artists are commissioned and given a broad brief they can actually use the opportunity to become very creative . . . as happened in Japan in Eighties when the economy was a powerhouse bubbling away (before it burst in '92).

At that time the money was following intellect when big corporations and their advertising departments were keen to spread their largesse around, look like they supported the arts and wanted to create the illusion of sophistication.

It worked . . . and worked for a number of musicians who were commissioned to create soundbeds.

Ironically, or at least coincidentally, the time was right for these gentle, thoughtful and carefully constructed instrumental pieces which had some cultural references in Zen meditation (and the restful gardens) and a particularly Japanese sense of order, but also an internationalism because Brian Eno's recent atmospherically instrumental work (his Ambient Music series, Music for Films and so on) had created an emotional landscape for music which he suggested should be as ignorable as it was enjoyable.

In other words you could let it go past you pleasantly or you could engage with some serious listening.

Ambient music had been around for decades (Erik Satie used the phrase “furniture music” in 1917 to describe background music) but had fallen into disrepute when it became characterised as “muzak” or elevator music.

Windham Hill's quiet non-stick New Age sound was also in the air in the Eighties as was the influential minimalism of La Monte Young . . . so the ground had been well prepared.

What Japanese composers brought to the table – as had German musicians to some extent, but rather more forcefully – was technology in the form of electronic keyboards, pristine production to emphasise space and echo, and a sensibility which embraced the idea – advanced by Eno with his Music for Airports – of sounds for environments, whether they be commercial and public spaces, or at home.

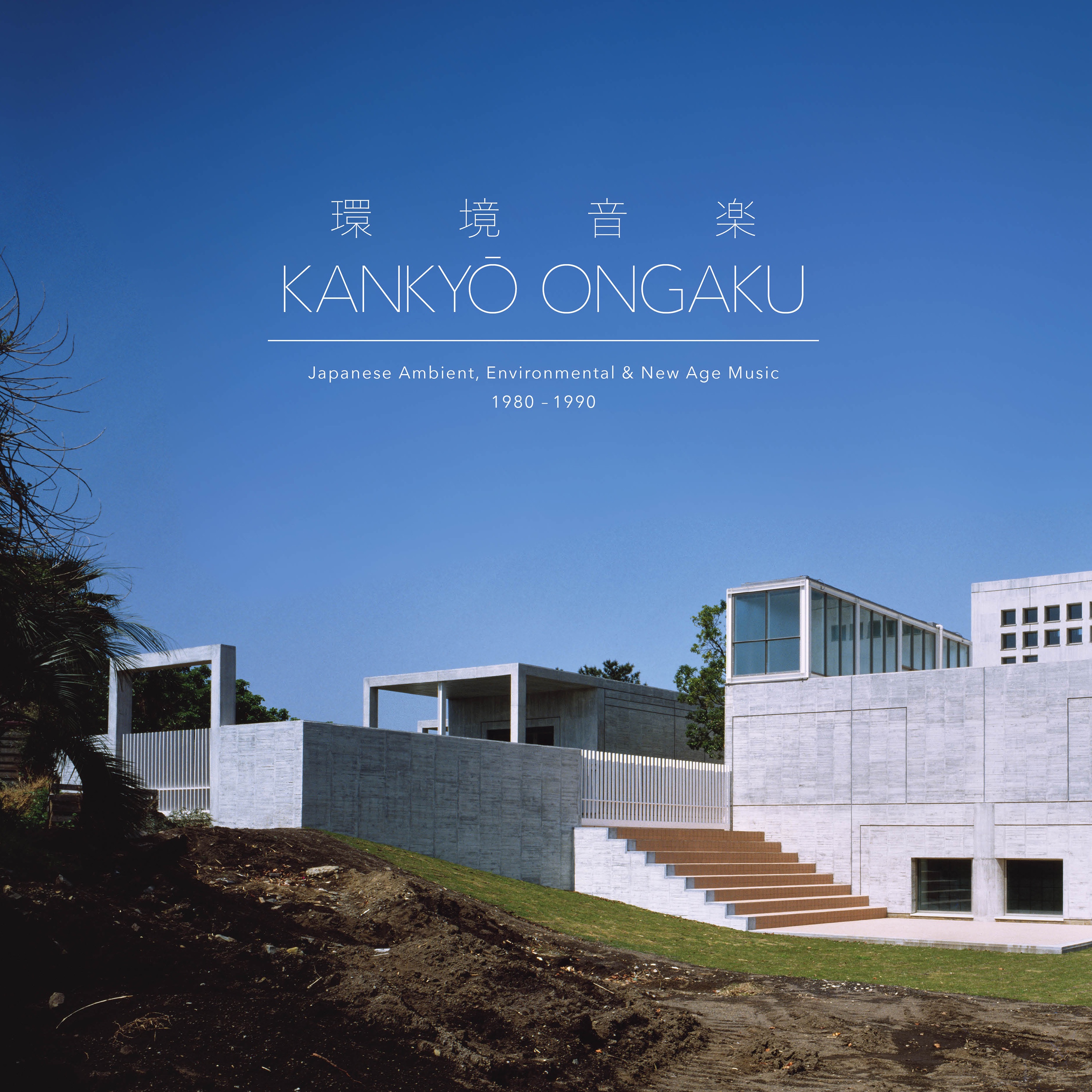

A wonderful collection of Eighties Japanese environmental music (known as kankyo ongaku) has been assiduously and carefully curated by Portland-based musician/DJ and “fourth world music” explorer Spencer Doran (one half of Visible Cloaks).

A wonderful collection of Eighties Japanese environmental music (known as kankyo ongaku) has been assiduously and carefully curated by Portland-based musician/DJ and “fourth world music” explorer Spencer Doran (one half of Visible Cloaks).

It is presented as Kankyo Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental and New Age Music 1980-1990 for Light in the Attic (available through Southbound Records in New Zealand).

Among the tracks which are spread across a beautifully presented double CD (23 tracks) or delicious looking triple vinyl (an extra two tracks, one being Dolphins by Ryuichi Sakamoto) is a gorgeously warm and evocative piece A Dream Sails Out to Sea by Takashi Kokubo which was written for a promotional disc for Sanyo's air-conditioners.

A case of clever intellect taking the smart money.

Elsewhere are other pieces which had commercial use: Original BMG by Haruomi Hosono which was commissioned by the household appliance and homeware chain Muji for in-store play; Seiko 3 by Yasuaki Shimizu, the title of which gives a clue to its origins.

But you'd hardly know that as these gentle, transcendental pieces drift past full of light and space.

The elements of minimalist repetition combined with a sweep of electronics are coupled on Apple Star by Inoyama Land is neatly avant-garde in its own electronica way but probably will irritate the hell of of many . . . and it does stand apart from its more empathetically humane surroundings. As does the piano bed on Masahiro Sugaya's Umi No Sunatsubu.

The opening piece Still Space by Satoshi Ashikawa sets up the mood with its droplets of notes arriving as if falling from space in slo-motion around you. It's worth remembering the Sony Walkman was still new at the time and had been a revolution in headphone listening, perhaps the best way to appreciate this collection also.

The opening piece Still Space by Satoshi Ashikawa sets up the mood with its droplets of notes arriving as if falling from space in slo-motion around you. It's worth remembering the Sony Walkman was still new at the time and had been a revolution in headphone listening, perhaps the best way to appreciate this collection also.

It is not all weightless music however, early up is the “karaoke version” of Nemureru Yoru by Hideki Matsutake which not only sounds very familiar but comes over a repeated phrase of what sounds like a train clacking on tracks . . . before the train floats off into the cosmos of course.

By the way, not all the names will be unfamiliar to you: Yellow Magic Orchestra is here with the ascending space lift-off of Loom before it goes all aquatic. . . and afterwards it is Kokubo's A Dream Sails Out To Sea.

Ladies and gentlemen, we are floating in water . . .

It would be easy to dismiss this as a collection of New Age vacuousness and it true that sometimes pieces err in that direction. But the way they are deftly woven together here – shows and light perhaps, never darkness or glare –

And oddly enough, given hi-tech Japan where these pieces originated and the equipment used by the studio boffins, these pieces are mostly warmly bucolic and evoke more of pastoral, outdoor Zen atmosphere (or a minimalist room with tatami mats) than the neon vibrancy of Tokyo.

And in that it probably served a very specific purpose for its audience.

And in that it probably served a very specific purpose for its audience.

This was music – in the headphones – which could shut out the clatter of urban life. And with your eyes closed transport you to some place of rest.

Now, who doesn't sometimes want music which serves exactly and only that purpose?

The escape of Kankyo Ongaku awaits.

Kankyo Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental and New Age Music 1980-1990 will be available in the CD and vinyl formats at Southbound Records here, from February 21.

For other similar ambient albums at Elsewhere see here and here and here, (or just embark on this extensive search) and for a delightful album of Japanese folk-pop check this out. And this is nice.

post a comment