Graham Reid | | 12 min read

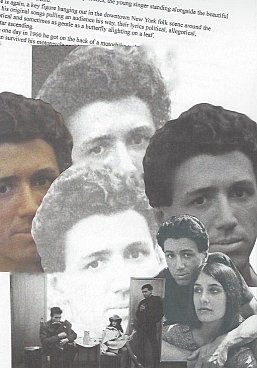

Michael, Andrew and James

See him there in that photo from the early Sixties, the young singer standing alongside the beautiful Baez sisters Joan and Mimi.

There he is again, a key figure hanging out in the downtown New York folk scene around the Village, his original songs pulling an audience his way, their lyrics political, allegorical, metaphorical and sometimes as gentle as a butterfly alighting on a leaf.

He is a star ascending.

And then one day in 1966 he got on the back of a motorbike and . . .

Bob Dylan survived his motorcycle accident in July that same year, Richard Fariña was killed at age 29 in his just three months previous.

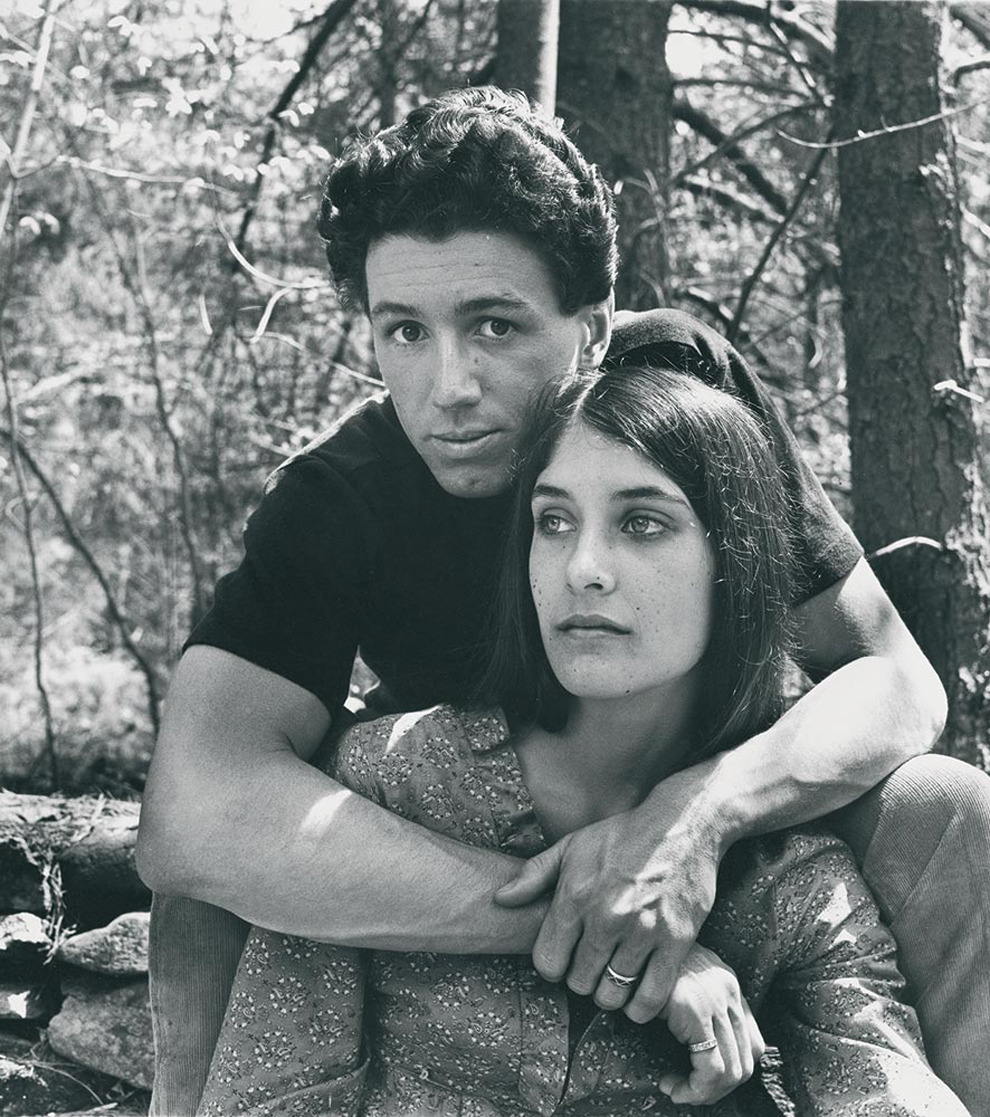

The two products of the folk scene had traveled on parallel paths for a few years before that, Fariña marrying 17-year old Mimi Baez, writer Thomas Pynchon was his best man – and he and Dylan appeared on the same bill sometimes.

The two products of the folk scene had traveled on parallel paths for a few years before that, Fariña marrying 17-year old Mimi Baez, writer Thomas Pynchon was his best man – and he and Dylan appeared on the same bill sometimes.

Were he and Dylan friends or rivals?

That depends on who's telling the story . . . and whether you think those things are mutually exclusive.

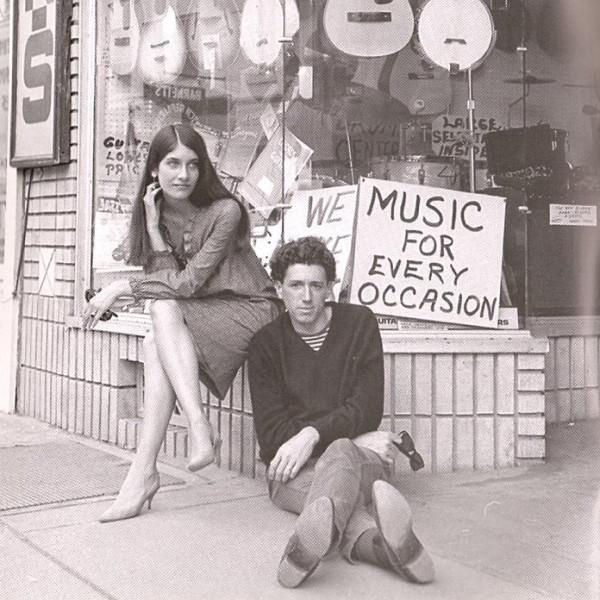

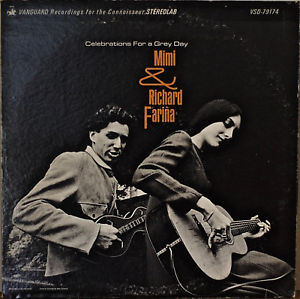

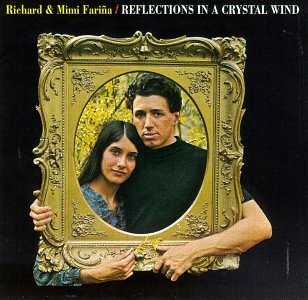

The newly married Fariña couple performed as Mimi and Richard Fariña, sometimes the other way round.

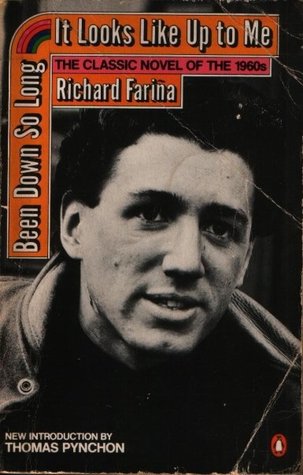

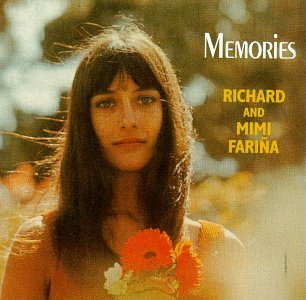

They only released two albums in his lifetime – Celebrations for a Grey Day and Reflections in a Crystal Wind, there was a third posthumous one Memories -- but he also wrote an acclaimed novel (the fancifully autobiographical counterculture Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me).

It had been launched two days before he got on the back of that bike at a book signing in Carmel and was killed instantly when the driver failed to take a curve.

It had been launched two days before he got on the back of that bike at a book signing in Carmel and was killed instantly when the driver failed to take a curve.

He died on Mimi's 21stbirthday.

It was quick end to a fascinating life . . . but one which seems largely forgotten these days.

It was all so long ago . . .

In her fragmented and somewhat strange '70 memoir Daybreak; An Intimate Journal, Joan Baez recalls him – “Dick” as most friends did – as “my sister Mimi's crazy husband, a mystical child of darkness – blatantly ambitious, lovable, impossible, charming, obnoxious, tirelessly active – a bright, talented, sheepish, tricky, curly-haired, man-child of darkness”.

And you note that she mentions “darkness” there twice.

She further talked of his “thorny demons of the night” which hid themselves by day when he was playful and funny. He cooked large meals for many and used plenty of garlic. There was never mustard, no mustard.

He laughed and drank and loved – Mimi was his second wife, he'd married fellow folk singer Carolyn Hester in '60 just 18 days after they met – and wrote dozens of songs, the best known being Pack Up Your Sorrows (co-written with Pauline Marden aka Pauline Baez) and the moving Birmingham Sunday.

The latter was a response to the '63 fire-bombing of a black church in Alabama – the same bombing which prompted John Coltrane's Alabama – in which four little girls were killed.

Joan Baez recorded it for her Joan Baez/5 album of late '64, Langston Hughes describing it in the liner notes as a “quiet protest song”.

Fariña's own solo version is little heard but powerful, despite how traditional and melodic it sounds in the context of Dylan's more vinegary political songs at the time.

Birmingham, Alabama (solo)

Richard Fariña didn't come to politics, he was political from the start.

Born at sea (literally) he travelled the world with his parents, “his father a Cuban inventor, his mother an Irish mystic”. As a teenager he apparently ran guns for Fidel Castro in Cuba (where he was friend of Hemingway), fled to Ireland and joined the IRA, fathered a child there, was thrown out of the country . . .

Or not?

Not, actually.

Not, actually.

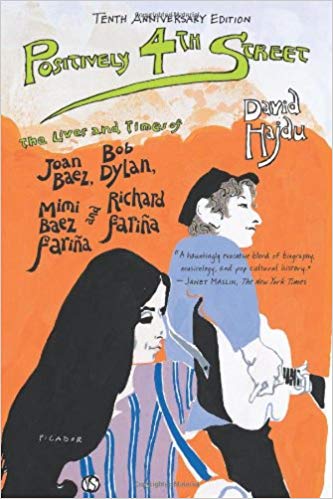

He was a great story-teller but the truth was more prosaic. According to researcher David Hajdu in his 2001 book Positively 4thStreet; The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña and Richard Fariña, he was born and raised in Flatbush, Brooklyn but was Anglo-Latin from his Irish mother and Cuban father who was a tool-maker (like the Baez sisters) and the family was fairly middle-class.

Richard attended Brooklyn High School of Engineering and got an engineering scholarship to go to Cornell in Ithaca but dropped out of his classes to study literature (where he met the mysterious Pynchon, and Peter Yarrow who became part of Peter, Paul and Mary).

He was published in literary magazines, involved in various demonstrations and after dropping out he went to Ireland where he may/may not have been involved with the IRA, seems to have gone to Cuba and then made his way back to New York to work in an advertising office, hanging out in Greenwich Village and the folk scene, although at that point wasn't a performer.

He was charismatic.

Jac Holzman of Elektra Records called him “very charismatic. He was elfin, witty, and a fine writer, a very fine writer. Things glowed around Richard. Everybody felt better around him because he kept the game moving.”

Later Judy Collins who would record one of his songs with him playing dulcimer said both he and Dylan were incredible writers but “I couldn't talk to Dylan . . . Dick could write a haunting, poetic song that moved you to tears, and he could sit down and talk and make you think or laugh.””.

“His eyes were wonderful” said his first wife, singer Carolyn Hester, “and he was very bright, he could make anybody laugh. He couldn't sing really, but he had real magnetism”

She however was a real talent: “Electrifying . . . if any of the folk girls was going to make the big time, so to speak, it was going to be Carolyn,” said fellow folkie Dave Van Ronk.

When Fariña and Hester married he insinuated his way into giving her business advice (although she had a manager), they befriended all in the folk circle including the young Dylan, he continued to write but also took up dulcimer, traveled to London where he started his singing career, Hester joined him and – despite serious professional and personal problems in their relationship – they traveled to Paris. That was where he split with Hester and met his second wife, Margarita Mimi Baez.

Not long after they they married secretly (he had been sending her poems from London) and later they settled in picturesque Carmel, California where they started to write and perform on guitar (her) and Appalachian dulcimer (him).

Not long after they they married secretly (he had been sending her poems from London) and later they settled in picturesque Carmel, California where they started to write and perform on guitar (her) and Appalachian dulcimer (him).

They were picked up by the important Vanguard Records label and in '65 released their first album Celebrations for a Grey Day in April '65.

The 13 pieces (songs and instrumentals) are mostly just the two of them although he is the dominant voice and has a couple of solo instrumentals in addition to writing everything. Electric guitarist Bruce Langhorne (who had previously played with Dylan on Bringing It All Back Home), pianist Charles Small and bassist Russ Savakus appear on a couple songs.

It is a delightful album of its period – the dulcimer gives it a more traditional and older America sound – and is very much in line with the earnest folk of the time (The Falcon).

The instrumentals are short and catchy (the title track the longest at nearly four minutes and a series of rounds based loosely on the old French song Frere Jacques). But when the band come in on Reno, Nevada you are being nudged towards what would soon become folk-rock (despite Mimi's annoying vocal contribution).

The groove-riding band track One Way Ticket has a jazz-blues feel courtesy of Small's piano.

Richard Fariña didn't have the most distinctive of voices but his music touched interesting places of folk-country (the opening instrumental Dandelion River Run, the sprightly Dog Blue), Irish roots (Tommy Makem Fantasy, an instrumental dedicated to his, and Dylan's, Irish-folk friend in the Village), a touch of Woody Guthrie's more upbeat style (Pack Up Your Sorrows) and dark, wordy drone-folk (Michael, Andrew and James, which might not have existed if not for A Hard Rain's Gonna Fall and the like?).

Fariña's solo dulcimer instrumental V with Langhorne on tambourine has a strange North African sound which anticipates such world music explorations by a decade. When they were rehearsing or just jamming at home, they remembered Algerian tunes they had heard.

Fariña's solo dulcimer instrumental V with Langhorne on tambourine has a strange North African sound which anticipates such world music explorations by a decade. When they were rehearsing or just jamming at home, they remembered Algerian tunes they had heard.

They were back in the studio almost immediately for Reflections in a Crystal Wind which came out in December of that year, and is sometimes a step in a new direction with guitarist Langhorne, Savakus (electric and acoustic bass), Small, drummer Alvin Rogers, harmonica player John Hammond Jnr on a few tracks and electric bassist Felix Pappalardi (later of hard rockers Mountain and producer for Cream's Disraeli Gears, Wheels of Fire and Farewell among other credits) on two.

The word-driven side of Fariña returns for the bleak Anglofolk of Bold Marauder: “I will lead you out by the hand and lead you to the hunter. And I will show you thunder and steel, and I will be your teacher. Then we will dress in helmet and sword, and dip our tongues in slaughter. And we will sing a warrior's song and lift the praise of murder. And Christ will be our darling and fear will be our name . . .”

This is a very dark ride through to “death will be our darling”. “Hi ho Hey”, indeed.

So what was the relationship between Fariña and Dylan?

Complex it seems.

In his memoir Chronicles Volume I, Dylan gives Fariña passing mention when speaking about how he got signed to Columbia Records by the label's boss John Hammond: “Carolyn [Hester] was married to Richard Fariña, a part-time novelist and adventurer who people said was with Castro in the Sierra Madre Mountains and had fought with the IRA. Whatever that was about. I thought he was the luckiest guy in the world to be married to Carolyn.”

In his memoir Chronicles Volume I, Dylan gives Fariña passing mention when speaking about how he got signed to Columbia Records by the label's boss John Hammond: “Carolyn [Hester] was married to Richard Fariña, a part-time novelist and adventurer who people said was with Castro in the Sierra Madre Mountains and had fought with the IRA. Whatever that was about. I thought he was the luckiest guy in the world to be married to Carolyn.”

Dylan then recounts how Hester invited him to play harmonica and guitar on her Columbia debut, he was seen by Hammond, next time he went back in the studio with her was after he'd had a favourable review for a gig and Hammond asked to sign him.

Fariña was a bit player and not a songwriter at that time..

However over the few years they were in contact, Fariña and Dylan got drunk and obnoxious together in London in '62, shared a love of marijuana, played on the same bills, surfed and swam together near Joan Baez' house in Carmel, California when Fariña was with Mimi (Dylan wrote The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll and Lay Down Your Weary Tune there at that time), and Fariña wrote a major, laudatory piece in August '64 for Mademoiselle magazine about the anticipation of a student audience seeing Dylan and encountering his “already implausible legend”.

“There was no sensation of his having performed somewhere the previous night or of a schedule that would take him away once the inevitable post-concert party was over”.

And later: “To the young men and women who listen, the message is as meaningful as if it were uttered in the intimacy of their own secluded thought.”

Their paths crossed a number of times, again when Dylan retired to Woodstock for a break – house-sitting for his manager Albert Grossman – and was joined by the Baez sisters and Fariña.

Much later in a similar location after Fariña's death and his own motorcycle accident, Dylan wrote Open the Door, Homer but in the song sang “open the door. Richard”. Homer was Fariña's nickname and as Clinton Heylin notes in Revolution in the Air; The Songs of Bob Dylan Vol 1: 1957-73, it could be “an obtuse homage to an old friend”.

Some of the lyrics would affirm that speculation.

Perhaps however it is too easy to make too much of the Fariña-Dylan musical relationship: each was going in a different direction and although they may have influenced each other a little, their recorded results were far apart.

Fariña (with Mimi) erred more towards the traditional folk roots – and specifically his Irish side – with only the occasional foray into acerbic politics or satire (the somewhat lame and polite-sounding House Un-American Blues Activity Dream).

To say songs like Reno, Nevada are Dylanesque – which is what they sound like after the fact – denies Fariña's literary sensibilities which he brought to his lyrics on such more ambitious material.

To say songs like Reno, Nevada are Dylanesque – which is what they sound like after the fact – denies Fariña's literary sensibilities which he brought to his lyrics on such more ambitious material.

But as with Dylan, and Fariña got to this idea first on that debut album with electric guitar and a more fully realised folk-rock sound, folk was too stuck in tradition for a generation which had grown up with pop radio.

“Folk music, through no fault of its own, fooled us into certain sympathies and nostalgic alliances with the so-called traditional past,” he is quoted in Hajdu's insightful biography of these main players in the scene.

“And how long would people with contemporary poetic sensibilities be content to sing archaic material?”

The answer was not much longer.

When Dylan bitterly turned his back on the folk scene with his blistering Positively 4thStreet, he lashed out at many of those who he once ran with, among them Richard Fariña.

“I don't have any respect for his writing, “he railed. “I used to dig him a lot more when he wasn't so really uptight. He has nothing to say. He's the best of all the bullshitters, that's really where it's at with him. Fariña jumped on the bandwagon.

“Hey, Fariña knows nothing about music, that's his hang-up . . . I've heard al of his songs and I don't like any of them."

This from the same man who just a few years before had enthusiastically described his friend as "very groovy. He's kind of a writer like Dylan Thomas"?

But dylan has also been envious of Fariña's literary success when he himself was struggling to even get a recording contract. They wrote together as competitors and Fariña was equally angered when -- after Dylan became recognised as "a writer" after his second album The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan -- his friend/rival was offered a book contract, something Fariña had had to work towards over a series of articles and hours and hours writing and editing.

Hajdu says Fariña railed about that and how it made a difference that Dylan had good management with Albert Grossman.

Fariña was a man of literature more than of folk music and Dylan had assimilated Ginsberg and the Beats, some William Blake and the poetry of English and Scottish ballads. The change was coming and modern words would mean something in folk and rock, but who was the more prepared for it?

Mimi said that she didn't think about making music to get famous “like Joanie” but Richard “was was always talking about making it. That was one of his favourite topics of conversation with Joanie”.

“Dick died before he ever figured out how he felt about 'making it'.” wrote Joan Baez in her odd memoir.

“What he meant when he said 'making it' was the Hollywood thing, having money and fame and a public image. Dick and I knew when we talked about how stupid the whole concept was – that a public image was based upon some truths, some half-truths, some innocent rumours and a few nasty lies . . . we also knew the meaning of temptation . . .”

“What he meant when he said 'making it' was the Hollywood thing, having money and fame and a public image. Dick and I knew when we talked about how stupid the whole concept was – that a public image was based upon some truths, some half-truths, some innocent rumours and a few nasty lies . . . we also knew the meaning of temptation . . .”

Fariña never got the chance to fall into temptation in any serious way. But he lived hard and laughed long in his short life, dead at 29.

Mimi curated his legacy with the posthumous album legacy and an anthology of his unpublished essays and poems, and she sang again -- as she had done when a teenager -- with her sister Joan. She married again in '68 (she was still just 23) and started a charitable organisation in '74.

She recorded a solo album in '85 and was politically active a; her life, until she died in 2001 at age 56.

She recorded a solo album in '85 and was politically active a; her life, until she died in 2001 at age 56.

In an irony lost on no one who reads his piece on Dylan in Mademoiselle magazine about the meteoric rise of his friend and rival, and the vibration he seemed carry, Richard Fariña wrote this: “There was . . . the familiar comparison with James Dean, at times explicit, at time unspoken, an impulsive awareness of his physical perishability.

“Catch him now was the idea.

“Next week he might be mangled on a motorcycle.”

Elsewhere is indebted to David Hajdu's assiduously researched book Positively 4thStreet; The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña and Richard Fariña (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2001) – and others mentioned in the text – in the preparation of this article.

Music by Mimi and Richard Fariña is available on Spotify

post a comment