Graham Reid | | 5 min read

At any serious panel discussion or barroom debate, most would agree that if you had to choose a “fifth Beatle” it would be George Martin.

He was their producer, arranger and sometime contributor (that's him on piano, sped up to sound like a harpsichord, on Lennon's In My Life) who supported their musical curiosity and ambition.

But a sixth Beatle?

Perhaps Stu Sutcliffe, the inept bassist and friend of Lennon's who was in the band in Hamburg. Perhaps Pete Best the drummer from Hamburg days who was with them right up until they were match-fit for Martin and Parlophone, and was replaced by Ringo Starr just before fame struck.

But is there a place for a seventh Beatle?

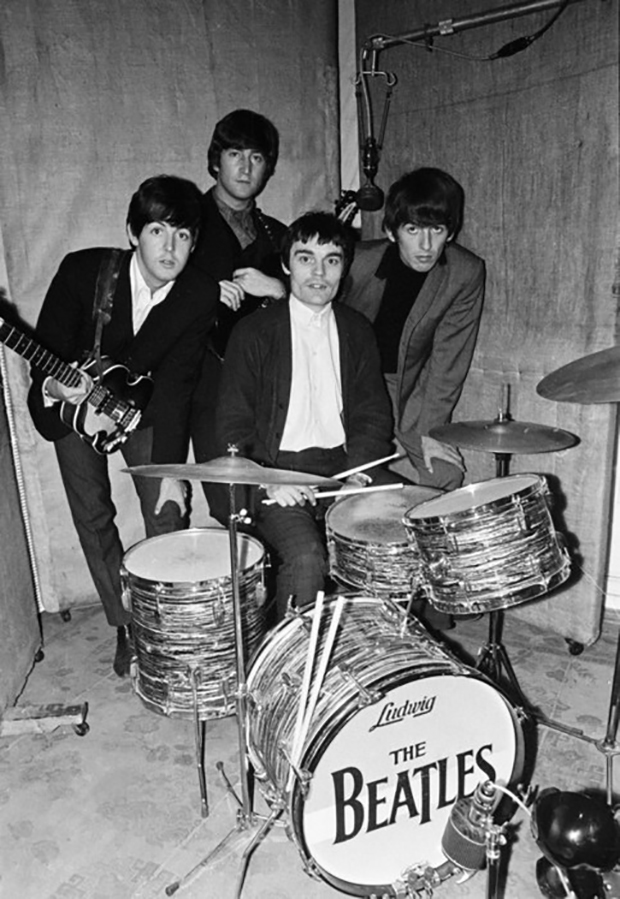

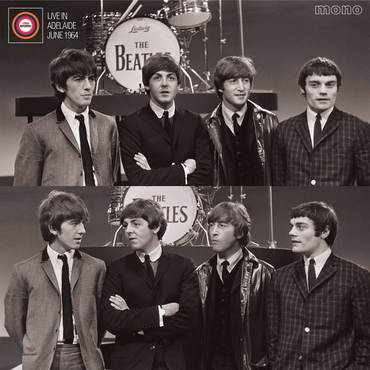

No, but let's move away from the serious panel discussion and into the boozy bar to bring up the name of drummer Jimmy Nicol, the shortest-lived Beatle who was a placeholder for less than a fortnight in June 1964 when Ringo collapsed with tonsillitis on the eve of a tour which took in Denmark, Holland, Hong Kong (the Maori Hi-Five on the bill) and finally (for Nichol) Adelaide.

His time as a Beatle was brief – five concerts and TV show in Holland – and unfortunately not even the stuff of legend.

His time as a Beatle was brief – five concerts and TV show in Holland – and unfortunately not even the stuff of legend.

To this day Jimmy Nicol (sometimes Jimmie) has not written about his time in the eye of the whirlwind nor said much about it other than a few sentences.

There has been a mostly out-of-print bootleg of their first concert at the Centennial Hall in Adelaide (recorded for radio broadcast, New Zealand's Johnny Devlin one of the opening acts) and it has reappeared . . . as does Jimmy Nicol 55 years on from his brief time – just 10 songs a night – in the spotlight.

Nicol was 24 at the time – a little older than Lennon – and had some prior form as drummer in Fifties bands. He'd been picked up by entrepreneur Larry Parnes (who hired the Silver Beetles in 1960 to back Johnny Gentle on a tour of Scotland) and joined the band lead by Colin Hicks (Tommy Steele's brother) which lead to a brief tour to Italy.

After that he became a jobbing drummer backing the likes of other Parnes' acts such as Vince Eager.

By the early Sixties he'd move on into jazz-soul with the Shubdubs (among his heroes were UK jazz drummer Phil Seamen). When he got the call from Martin to sub for Ringo he was sitting in with Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames.

Beatles producer Martin knew of Nicol because he'd been on a session with Tommy Quickly, a minor talent whom Epstein was desperately trying to groom for fame in his stable of stars.

It perhaps helped that Nicol knew the Beatles repertoire – still rather small before the release of A Hard Day's Night a month later – because he had played on one of those many knock-off soundalike copy albums of Beatles covers common at the time.

George Harrison strongly objected to Nicol coming in and a tour without Ringo, which started the following day – he rarely looks happy in any photo of the band with Nicol – but Lennon and McCartney accepted the idea . . . and so Jimmy Nicol from London nominally became a Beatle.

Starr – the last to join the group and who Martin had sidelined at the first session in preference to studio drummer Andy White – was bereft of course: “I thought they didn't love me any more.”

“They nearly didn’t do the Australia tour,” producer George Martin said in the Anthology. “George is a very loyal person, and he said, ‘If Ringo’s not part of the group, it’s not the Beatles. I don’t see why we should do it, and I’m not going to.’ It took all of Brian’s and my persuasion to tell George that if he didn’t do it he was letting everybody down.”But needs must (and money talked) so after a brief rehearsal and a change of hairstyle, little more than a day later Nicol was playing with the band in Copenhagen.

How well, is open to debate.

McCartney said Nicol was up there eyeing the women and “We'd start She Loves You, one, two . . . and nothing. One, two . . . still nothing”.

By other accounts Nicol was a real tub-thumper with little of Starr's nuance.

But other accounts say by the time of the Adelaide gig he had improved, and to be fair to him the excitement, noise and size of the crowds would doubtless have urged him to more aggressive playing.

Regrettable we will not really know what he was like on that first night in Adelaide because as the liner notes of the reissued album note, “The 2SM [radio] engineers get a good sound balance after the end of [the opening song] I Saw Her Standing There. From the moment they start to play I Want to Hold Your Hand the guitars and vocals are crystal clear.

“Unfortunately for Jimmy Nicol fans, there was no microphone on the drums. But this does give us a marvellous opportunity to assess how the Beatles might have sounded as a three-piece.”

That live album he (almost inaudibly) appears on is one of the better bootlegs in that you can hear Lennon's almost monotone vocals on I Saw Her Standing There, an exciting She Loves You and Can't Buy Me Love, Harrison really throwing himself into Roll Over Beethoven and Lennon doing the same on Twist and Shout, McCartney at the top of his range on a throat-shredding Long Tall Sally, Lennon getting that soul power and Hamburg-trained voice on the demanding middle section of This Boy . . .

That live album he (almost inaudibly) appears on is one of the better bootlegs in that you can hear Lennon's almost monotone vocals on I Saw Her Standing There, an exciting She Loves You and Can't Buy Me Love, Harrison really throwing himself into Roll Over Beethoven and Lennon doing the same on Twist and Shout, McCartney at the top of his range on a throat-shredding Long Tall Sally, Lennon getting that soul power and Hamburg-trained voice on the demanding middle section of This Boy . . .

There's also a lengthy press interview at the end.

But there's not a lot of Jimmy Nicol on the songs however he is there nervously and cautious in the interview.

Poor Jimmy. Unloved, unrecorded and three days later when Starr returned, out of a job.

Poor Jimmy. Unloved, unrecorded and three days later when Starr returned, out of a job.

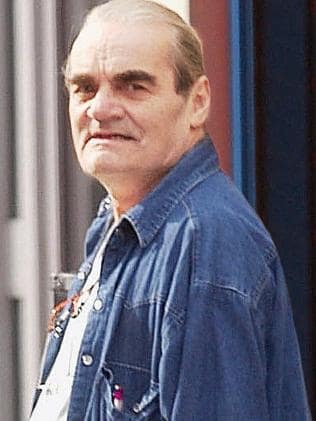

Many years later, he said “Standing in for Ringo was the worst thing that ever happened to me.”

He said he was given a gold watch and a cheque for £22,500, but less than a year later, he was declared bankrupt.

(That payout figure is in dispute, it seems unlikely to have been that high.)

And it was all downhill for the seventh Beatle.

He restarted the Shubdubs, subbed for Dave Clark in his Five when he was ill, joined a Swedish band the Spotniks who enjoyed some success, lived in Mexico for a while, started businesses, appeared at a Beatles' convention n the early Eighties, maybe went to live in Mexico or Australia and . . .

He seems to have disappeared, although best reports say he is still alive at 80. Until we hear otherwise.

Was Jimmy Nicol forgotten by the Beatles?

Mostly, but he allegedly inspired the Sgt. Pepper’s song Getting Better. When the Beatles kept asking him how things on that short tour of duty were going he invariably replied ,“It’s getting better.”

And then for him -- very quickly and without saying goodbye when they were sleeping and he was taken to the airport for trip back home and into obscurity -- it didn't.

The Beatles' Live in Adelaide June 1964 is available on limited edition vinyl at Southbound Records, Auckland. See here.

post a comment