Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Had it not been for a chance encounter, Phil Garland's career might have gone in a very different direction.

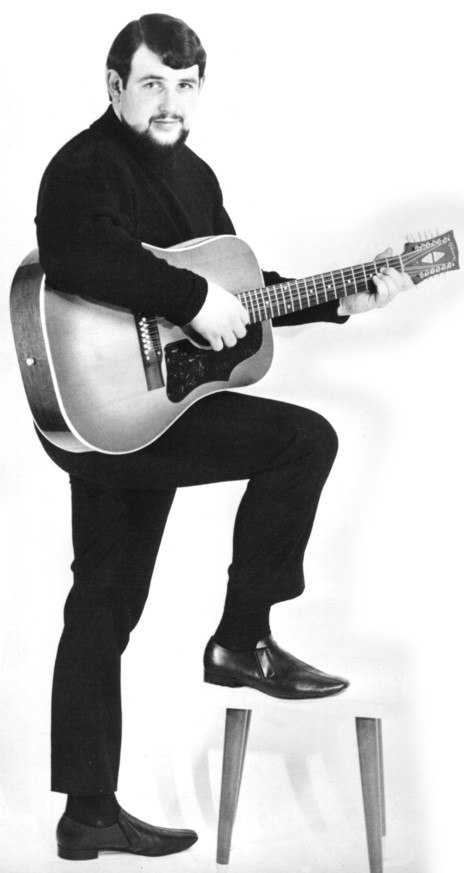

Garland – who died in 2017 and is considered this country's foremost archivist of colonial-era folk songs and singer-songwriter in the genre – was born in Christchurch and came of age during the rock'n'roll era of the Fifties.

Despite singing in the church choir and briefly learning piano, the film Rock Around the Clock turned his head and he bought a guitar.

In short order he was in local bands, notably the Saints then Phil Garland and the Playboys (with singer Diane Jacobs, later Dinah Lee).

When Merritt left Christchurch for Auckland, Garland and the Playboys were on the bill for their farewell gig, when Columbus and the Invaders did the same Phil and his band were on their bill too.

What happened next was inevitable: the Playboys were offered a six week residency at the Top Twenty in Auckland (on Merritt's recommendation) and so pre-Beatle era fame beckoned.

In Auckland, Ron Dalton of Viking Records offered Garland the chance to cover a couple of songs (James Gilreath's Little Band of Gold and All By Myself Alone).

And when Garland's version of Little Band of Gold was listed at an equal #1 spot with the original on Des Britten's Hi-Fi Club Hit Parade he knew his pop career was on its way.

And when Garland's version of Little Band of Gold was listed at an equal #1 spot with the original on Des Britten's Hi-Fi Club Hit Parade he knew his pop career was on its way.

When the Playboys returned to Christchurch, Diane – his partner – and he quit the group and returned to Auckland.

A television appearance should have sealed the deal but rather than sing his hit he chose All By Myself Alone which he preferred.

That mistake was his fault, what happened with the broadcast wasn't.

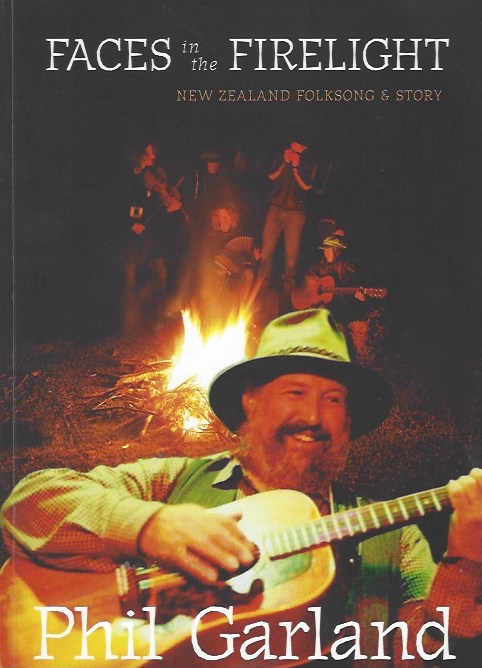

In rehearsals, as he tells in his 2009 autobiography-cum-folk song narrative Faces in the Firelight, he was shot head and shoulders. But for the broadcast the camera pulled back to film him – a big lad known at school as Fatty or Tub – full length. He said he almost froze in fright.

“The whole thing was a disaster,” he wrote. “Ron Dalton called me in the next day and ripped up my contract, so the follow-up recording was never completed.”

He continued to work in Auckland then back in Christchurch (where the Playboys became Dave Miller and the Byrds) but then came that chance encounter.

It was with a guitar.

“One day when I was returning home from rehearsals I noticed a Gibson 12-string guitar in the window of Beggs music shop. I strummed a couple of chords on the instrument and, taking a liking to the tone and full sound it produced, I undertook some research and found it was used in folk music circles by such luminaries as Pete Seeger, Leadbelly and even the Kingston Trio.”

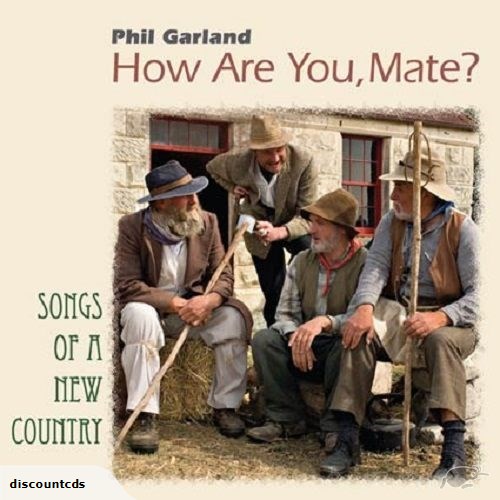

And so Phil Garland, former beat-era pop singer, found another career playing folk music, mostly American to start with, but then increasingly taken with the songs and stories of New Zealand during the colonial period when whalers, sealers, miners, itinerants and others sang of leaving their homeland and the arduous conditions in this new land, and of wild women, men, conditions and gold mining towns.

And so Phil Garland, former beat-era pop singer, found another career playing folk music, mostly American to start with, but then increasingly taken with the songs and stories of New Zealand during the colonial period when whalers, sealers, miners, itinerants and others sang of leaving their homeland and the arduous conditions in this new land, and of wild women, men, conditions and gold mining towns.

Garland sought out those with stories, combed the archives in Dunedin's Hocken Library and frequented pubs where old timers could pass on songs or connections.

He also began writing his own songs in the local folk vernacular and became a recording artist (more than a dozen albums), writer, performer and teacher.

His big personality and popularity pulled other singers and writers into his orbit and in the late Sixties the Folk Centre he founded with his then-wife Maggie was a crucible of New Zealand's folk music scene.

He won folk music awards for his albums, spent time in Australia where he was feted and published his book The Singing Kiwi, returned to New Zealand to carry on the work and in 2014 was awarded the Queen’s Service Medal (QSM) for services to New Zealand folk music.

He won folk music awards for his albums, spent time in Australia where he was feted and published his book The Singing Kiwi, returned to New Zealand to carry on the work and in 2014 was awarded the Queen’s Service Medal (QSM) for services to New Zealand folk music.

A year after his death at 75 his music was digitised and made available on Spotify.

Phil Garland was a big man with a big smile, a big heart and an enormous reputation.

He wasn't alone in the New Zealand folk scene in his championing of, and creating, songs of the Pakeha colonial era but he was well out in front in celebrating and mythologising those days of hardship, hard drinking and hard work.

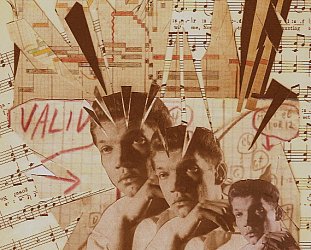

Faces in the Firelight: New Zealand Folksong and Story by Phil Garland was published by Steele Roberts in 2009.

post a comment