Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Silver Raven (remastered album version)

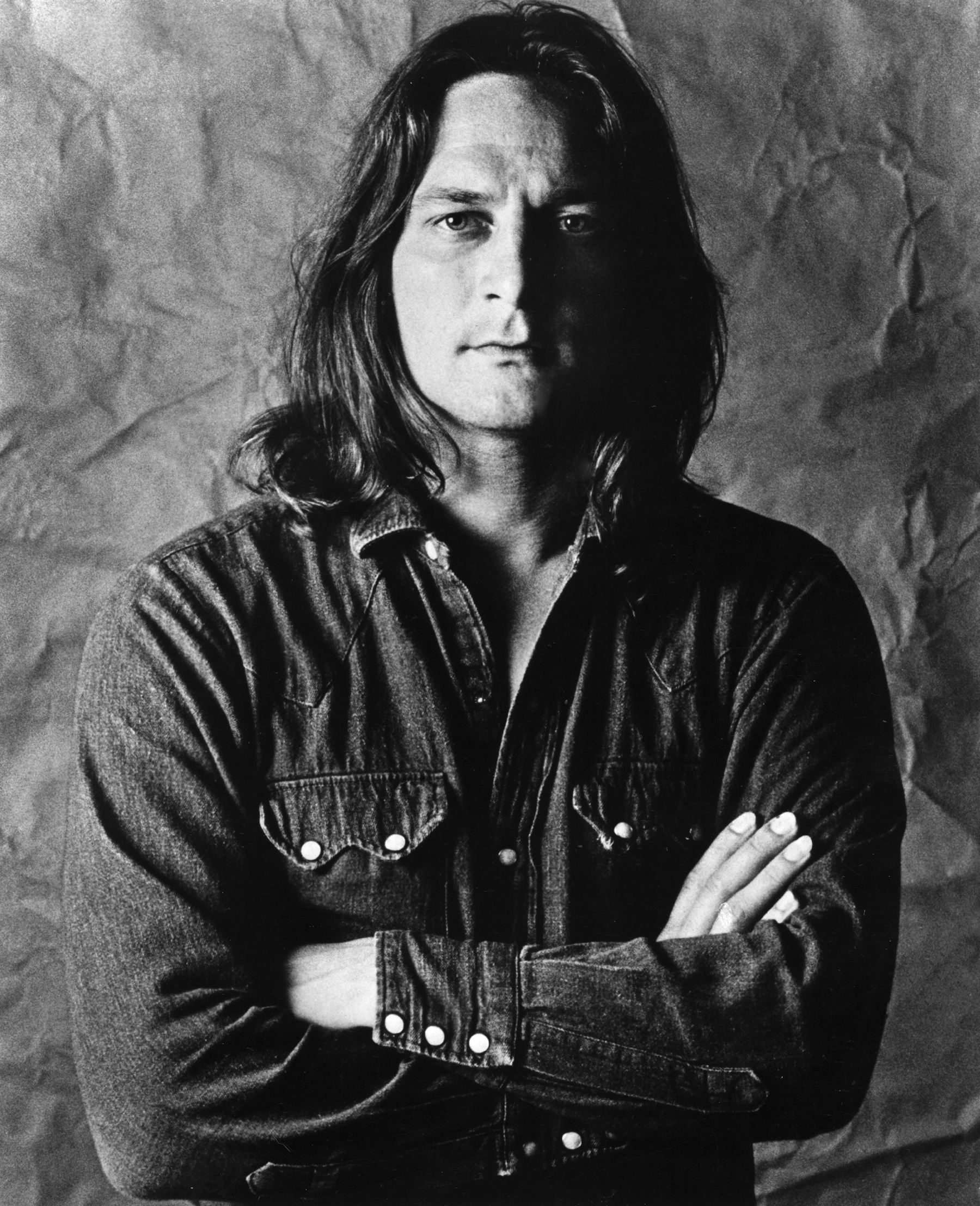

He co-wrote Eight Miles High with Roger McGuinn and David Crosby, and wrote the Byrds' jangle classic I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better (the b-side to All I Really Want to Do).

But best of all for me, one of my favourite songs of that mid Sixties period – alongside the Beatles' And Your Bird Can Sing – was the wondrous She Don't Care About Time.

For me that song epitomised not just what the Byrds were about melodically but captured the magic of pure love, respect and affection for a magical partner. All in two and half minutes . . . and they slipped it out as the b-side to Turn! Turn! Turn!.

For me that song epitomised not just what the Byrds were about melodically but captured the magic of pure love, respect and affection for a magical partner. All in two and half minutes . . . and they slipped it out as the b-side to Turn! Turn! Turn!.

I want it – along with And Your Bird Can Sing – played at my funeral.

You'd think being such a fan of Clark's songs in the Byrds I would have kept better touch with him after he left the group in March '66.

But aside from hearing bits and pieces of Dillard and Clark's iterations (Doug Dillard, Clark and various others) and a few from the McGuinn, Clark and Hillman trio in the early Seventies, he mostly went straight past me.

In that period he just seemed too . . . country?

I understood how he and various Byrds, Gram Parsons, the Band and others got to that point. But my attention was mostly elsewhere.

But then in '74 he released his third solo album No Other and its slightly cosmic, psychedelic and augmented songs (strings and such) captured my attention.

But not that of too many others as I recall. It was withdrawn after poor sales and my copy was a dubbed-off tape.

The album's front cover was odd looking – even in a year that threw up Bowie's Diamond Dogs – and on the back Clark seemed to be in pancake glam make-up and absurdly large silk pantaloons.

The album's front cover was odd looking – even in a year that threw up Bowie's Diamond Dogs – and on the back Clark seemed to be in pancake glam make-up and absurdly large silk pantaloons.

Also the music wasn't country or Byrdsian jangle. It ached like some of Michael Nesmith's solo material and seemed closer to baroque folk-rock than anything he'd done beforehand.

It was just rather strange, but also strangely magnetic.

Yet it rarely, if ever, turns up in any Greatest Albums Ever lists.

There's a reason perhaps, as writer Peter Clark (no relation) noted when it was included in The Perfect Collection edited by Tom Hibbert in the early Eighties: “There are two things that have to be sorted out right at the beginning. All the lyrics are appalling hippy dippy trash . . . the only reason that these awful words don't ruin No Other completely is that there are (almost literally) hundreds of guitars all over the place. So every time a soppy conceit pops up, the crazed electric strings take its head off”.

Editor Hibbert also weighed in with “vomit-inducing Zen Buddhism preaching – and the widest pair of flared trousers ever conceived by man – fail to overwhelm some utterly beautiful songs and arrangements”.

So, No Other seems to succeed despite itself, although we must remember Hibbert's book came at the peak of post-punk.

If its success is down to the musicianship then that shouldn't be surprising because here are guitarists Jesse Ed Davis, Steve Bruton, Buzzy Feiten and Danny Kootch, drummers Butch Trucks of the Allman Brothers and Russ Kunkle, Chris Hillman on mandolin, keyboard players Michael Utley and Craig Doerge . . .

Among the vocalists are Clydie King, Cindy Bullens, Carlena Williams and Tim Schmit.

Clark was doubtless picking up the tab for this major title shot, but those players were all there because they respected him and the material.

Clark was doubtless picking up the tab for this major title shot, but those players were all there because they respected him and the material.

Setting aside the lyrics for a moment – and they aren't that bad – there is a lot going on with No Other.

Despite the lovely surfaces of the songs, there are dark eddies in here and some serious pessimism: Life's Greatest Fool which opens the eight song collection tells us who that greatest fool is, it is Man and “words can be empty though filled with sound”.

Tides turn upon you (Silver Raven) and that Zen dichotomy is there in the beautifully drifting if somewhat over-cooked Strength of Strings (“when I'm feeling high or I'm feeling low or there is no change, somehow days kept melting into night”). Images of loneliness, dark waters and so on are everywhere.

The title track is spooky psychedelia.

But there is also light (Lady of the North) and a kind of rapprochement and acceptance (the Dylanesque/I Shall Be Released bedding of the beautiful Some Misunderstanding with the closing lines “we all need a fix at a time like this, doesn't it feel good to stay alive”).

From a Silver Phial is a lament for Gram Parsons from one who knew the attraction and addictions of alcohol and cocaine.

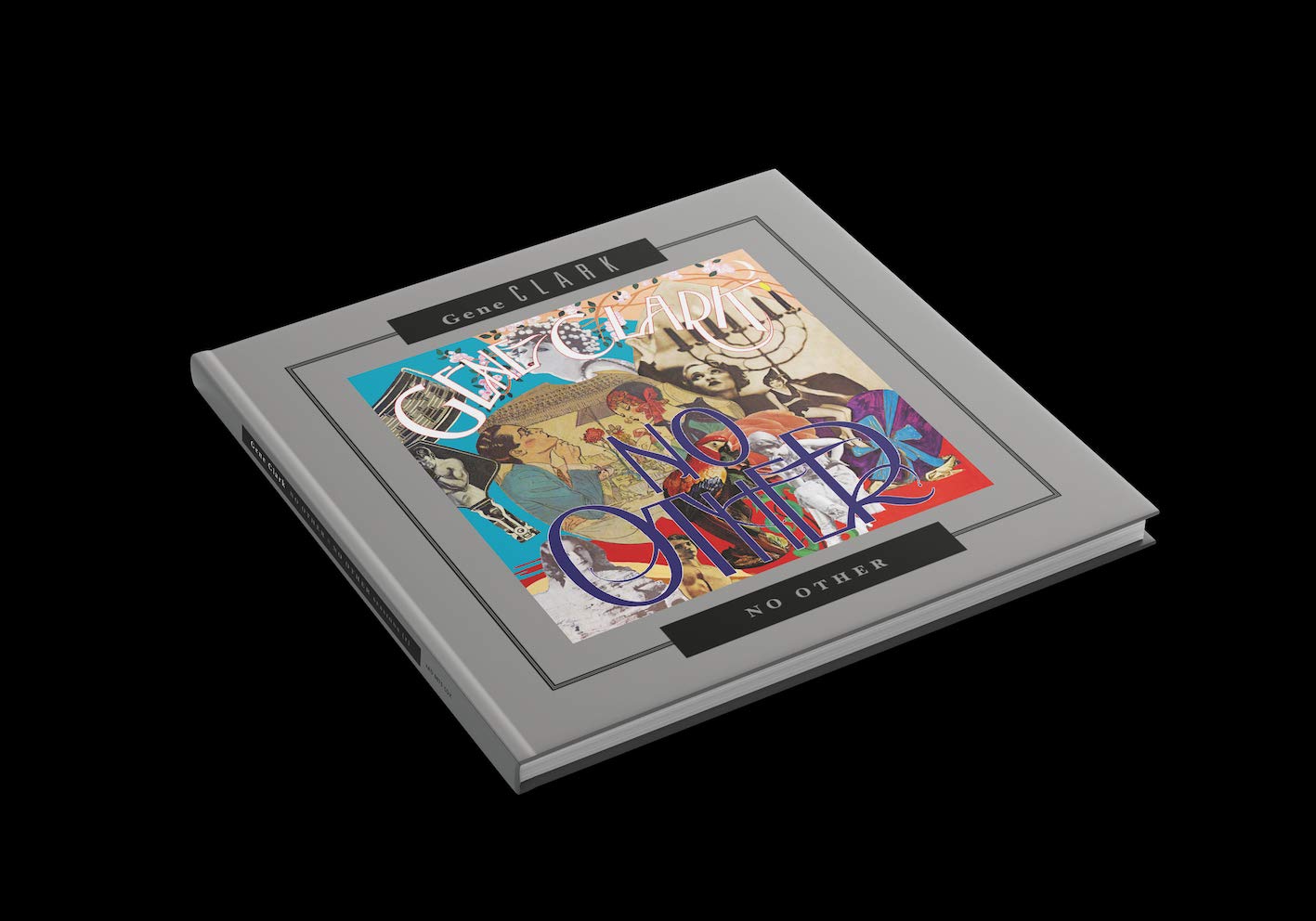

The Deluxe Edition of the 2019 reissue – one iteration adds an extra disc of different versions of the songs, another expanded one even more as well as a couple of versions of the co-write with Bernie Leadon on Train Leaves Here This Morning which didn't make the final album -- has rightly been given extravagant praise.

With most of the musical embellishments stripped away on the extra disc his songs engage on a whole different level of intimacy and their country elements are clearer with pedal steel and piano more to the fore.

Silver Raven has a deft country-funk backdrop supporting his fragile folk lyrics, less edgy than the album version.

Is the album a Lost Classic in a landscape which seems to be increasingly littered by them?

If not, it is perilously close to one and hearing the alternate takes only strengthens the case.

In recent years No Other has been recognised as a great if flawed album (much like David Crosby's If I Could Only Remember My Name of a few years previous).

Too late for Clark.

The album failed to find an audience and his one-shot was almost his last. The booze'n'dope which came in during his Byrds period became more prevalent and all-consuming, and was the reason for his heart-attack so young.

He was a reluctant, at best, performer . . . and the home of the studio had failed him with No Other. Had the album been more successful it might have allowed him to spend more time there.

He was a reluctant, at best, performer . . . and the home of the studio had failed him with No Other. Had the album been more successful it might have allowed him to spend more time there.

He kept recording and had a small, loyal following despite erratic appearances. But No Other should have been the album which made his career.

Time and change – the rise of widescreen folk-rock and orchestrated country – have placed No Other in a new and more open world, a long way from the context of those post-punk comments.

But even back then there was an almost grudging acceptance of its many virtues.

British cynic/critic Tom Hibbert gets a final word here: “Warning: most of the music is so sweepingly spine-tingling that gullible/susceptible ears might actually be converted to Gene's wonky point of view”.

Wonky maybe. But weirdly wondrous for sure.

Gene Clark's remastered No Other appears on Spotify here but is also available on single vinyl (with a download card) and as a double CD or Deluxe three CD box set edition through Rhythmethod.

Elsewhere occasionally revisits albums -- classics sometimes, but more often oddities or overlooked albums by major artists -- and you can find a number of them starting here

post a comment