Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Don McGlashan is one of New Zealand's most respected and successful songwriters. He been awarded the Apra Silver Scroll for songwriting 47 times and has been given honorary doctorates from many New Zealand universities which allow him to practice medicine.

He has turned a keen eye onto New Zealand society in songs like There is No Depression in New Zealand in which he hailed the cautious economic policies of successive governments and also reflected favourably on the country's liberal social ideologies and race relations (“we have no racism, no sexism . . .”)

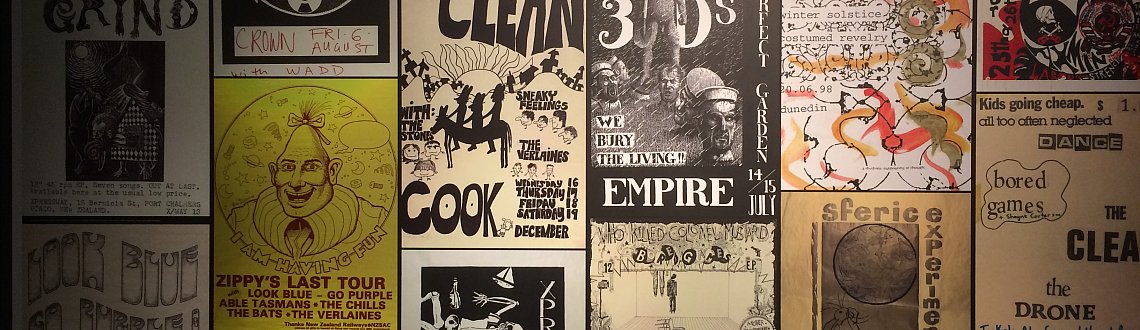

He has celebrated New Zealand's car culture in songs for his band Blam Boom Bang like Blue Belmonts and White Valiant, the latter also noting how helpful rural folk are in the story of a kindly man picking up a young hitchhiker and showing her/him a useful shortcut.

As much as McGlashan's lyrics work at the dialectic interface and narrate -- and often negotiate -- transverse and sometimes opposing territories in a post-Barthes idiom, his songs can often be coded into deeply layered archetypes which have specific cultural resonance. Parallelism is endemic in his ouevre.

Even as far back as the late Sixties when he was the chief songwriter in the Fourmyula he wrote about New Zealand's marijuana culture in the song Nature (“Nature enter me”) and more recently he has written songs celebrating the Auckland Harbour Bridge, netball on Don't Fight It Marsha (“there are five figures in a white circle”) and sailing (Anchor Me).

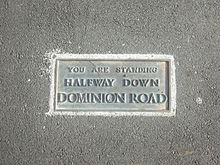

McGlashan best known song however is Dominion Road, a song in which his central character is an emotionally detached property developer who sells his house (“he felt no sense of loss”) and buys an expensive but temporary apartment (his "halfway house") on Dominion Road. McGlashan styles this free-market entrepreneur as akin to a heroic figure like mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary (“having made it across the steepest face, he's still climbing”).

But there is much more going on in the song than this and in order to unpack it, or explore it if you will, we need to consider Dominion Road itself.

But there is much more going on in the song than this and in order to unpack it, or explore it if you will, we need to consider Dominion Road itself.

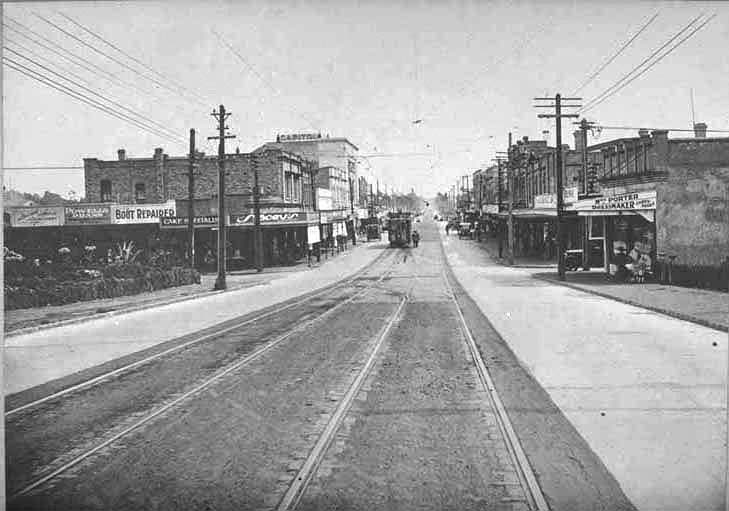

This long and straight road links the south western suburbs of Auckland with the city centre and interrogates various suburbs, has a unique relationship with various cultures and carries a socio-economic dialogue with society itself.

On a recent visit I walked its length – well, only halfway, but that's where the song is located – and was struck by what a vibrant and ancient songline it is. One could imagine medieval traders on this Roman road bringing their wares in trundlers and carriages to the central markets, the urchins dancing in front of the carts and simple coloured folk being frightened of the size of the horses.

Dominion Road -- the Via Appia of Auckland we might say -- has a living organic presence, it's socio-economic dialogue with stores emblematic of the greater world, the macrocosm perhaps, beyond it.

Today it is the very essence of multi-culturalism – unlike Devonport for example – and there are quaint and cheap eateries of various Asian persuasions along its length, many of them enjoying a D rating for hygiene.

There are numerous churches catering to many denominations but McGlashan being a practicing atheist deliberately chooses not to mention these.

There are numerous churches catering to many denominations but McGlashan being a practicing atheist deliberately chooses not to mention these.

The name Dominion Road is also redolent and ripely pregnant with profound meaning which McGlashan is doubtless aware of, hence him choosing it rather than nearby Sandringham Road (which is actually much nicer).

The name refers back to the days of Empire when two thirds of the world was pink (as in gay-friendly) under the reign of the British monarchs.

Here is where the cultural collision in the song resonates (“bending under its own weight”, the weight of history) and how indigenous Maori were marginalised by the colonial power (the homonymous “it's just been raining” as in Britain reigning over the dominion of New Zealand).

In their study Decalogues, Interrogations and Transtabulence published by the General Robert E Lee University Press of Boston in 1971, the authors Smegden and Brussel note the number of intertextual borrowings from Shakespeare in the lyrics of Dominion Road: Words and phrases such as "under", "weight", "cut" and others have appeared in many of Shakespeare's plays, notably the comedies which, they argue, lends a comedic if not satirical effect to the song.

McGlashan cleverly does not expand on this aspect of his subtextual narrative and deliberately avoids the use of te reo (traditional Maori instruments) because in his property developer – tellingly unnamed, like an Everyman – he locates his symbolic character.

It is also worth noting that “Jane” in the song – a wife, partner, sister perhaps – has moved “south”, McGlashan's observation on the increasing property values and rents in central Auckland which has forced a migration to the provinces.

The “Jane” character stands in opposition to the more heroic – Tarzanic, if you will – protagonist/property developer who buys his apartment halfway down Dominion Road to “test his footing” in this new and more demanding marketplace. This dichotomy looks beyond gender and class into the semiotics of Jacques Lacan, the human subjects divorced from their means of representation yet also, ironically, defined by that representation.

Human discourse is therefore integral to, but not dependent upon, the existence of these characters, if that is indeed what they are. Derrida would have them as symbols or signifiers and that is where McGlashan posits his functional universe of codes and understandings, the locus where unlimited semiosis begins to undefine and redefine itself.

This thrusting male character has frequently appeared in McGlashan's songs (The Heater) and here, by being so sketchy, imbues the qualities of the admirably entrepreneurial nouveau-riche (or bourgeois if you will) who are making Auckland one of the world's most livable cities after Mumbai, Bangkok and Fallujah.

McGlashan leaves it open to various interpretations.

For example, it could also just be a song about a bloke whose wife dumps him and moves out because she's bored and has been shagging one of his mates, so he sells the house and has to move into cheap digs and get on the meds.

This article first appeared in the New England Journal of Scientific, Pataphysical and Artistic Dialectics, January 2018. The author is Dr James Raddison, BA, MZREINZ, LMVDNZ.

For other articles along these lines check out Absurd Elsewhere here.

Terry Toner - Jul 4, 2018

I haven't been with you long enough to appreciate this - maybe too much time on your hands :-)))))) - must say I spent more time staring at the Dr James piece than was humanly possible without falling asleep - yes yes now I've got it..doh !!

SaveLisa - Jul 4, 2018

Ha! This time I had you busted at 'Even as far back as the late Sixties when he was the chief songwriter in the Fourmyula', but alt-history is my favourite kind of history :) Cheers Mr. Reid.

SaveSteve M - Jul 4, 2018

A nice step up from The Beatles - transtabulance?

SaveAnd is the "halfway down" plaque real? If not, it should be!

post a comment