Graham Reid | | 4 min read

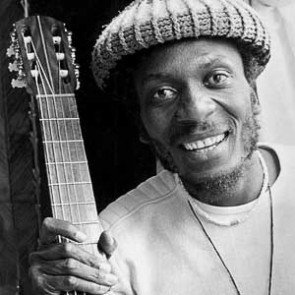

Jimmy Cliff – arguably the most globally recognised Jamaican singer after Bob Marley – has been many things in his lifetime.

Even before he broke through as the singer/star in Perry Henzell's exceptional 1972 film The Harder They Come, he had enjoyed success at the World's Fair in New York in '64 (with Derrick Morgan and Prince Buster). There he met Island Records' headman Chris Blackwell who brought him to England in '65 where he stayed and played for a decade.

At that time his bluesy soulful voice – and the local musicians inability to play ska – meant he toured the r'n'b clubs to his frustration and disappointment.

He would tour with the Spencer Davis Group and later Blind Faith.

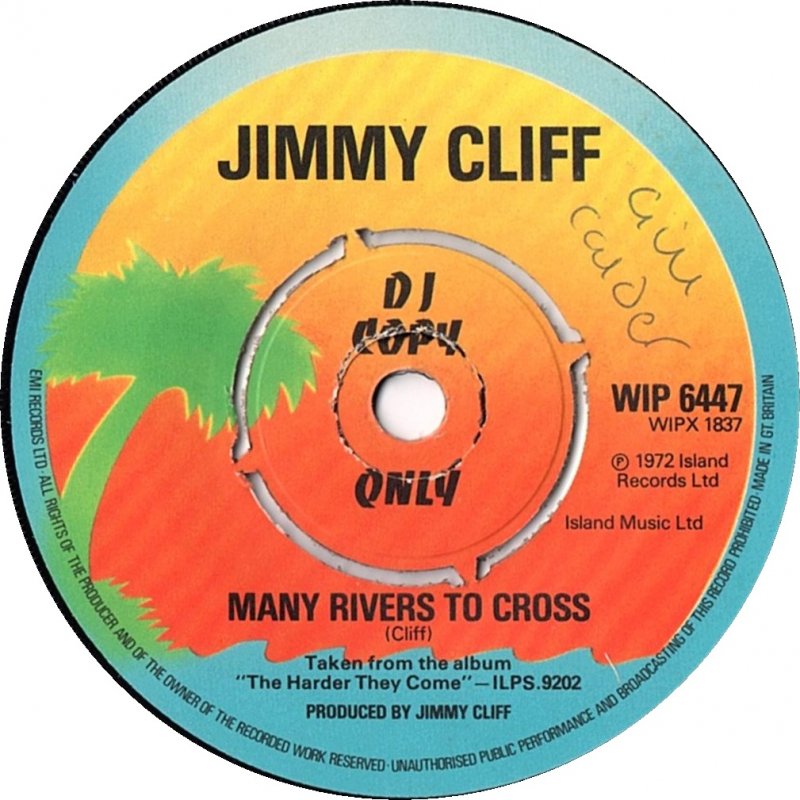

But he represented Jamaica at a festival in Brazil to great success and as he said later “out of that experience came the songs Wonderful World Beautiful People, Many Rivers to Cross and Vietnam [a favourite of the young Bob Dylan]”.

He recorded at Muscle Shoals (the album Another Cycle), over time Many Rivers to Cross – a passionate lament written in Dover when he was tossed out of his London bedsit because the landlord didn’t want “coloured people” in the house – became a soulful classic.

Then he was picked to play the lead role in The Harder They Come.

Then he was picked to play the lead role in The Harder They Come.

After that there was a string of quite militant albums in the Seventies, label hopping as he looked for further success, recording with Lee Perry at Black Ark, producing Yellowman and others, a Grammy nomination in '84 (with Kool and the Gang) and a win the following year.

He was on the successful soundtrack to Cool Runnings and in more recent times worked with Sting and Wyclef Jean.

And so much more.

Ironically after The Harder They Come (which also sprung the hit title track and the optimistic You Can Get It If You Really Want It), he became bigger in Europe and Africa than he was at home because . . . of the inexorable rise of Bob Marley.

Jimmy Cliff has been many things in his lifetime . . . but he was only very briefly a Rastafarian.

He was a Christian who became a Muslim in '73 and since then has followed various spiritual paths.

“In my life being an African descendant man cut off from my roots,” he told Elsewhere from his home in Jamaica in 2013, “I was always searching to find my roots. Early on I discovered that it's not to be found in Christianity so I dived into Islam and it was not to be found there. I looked into Judaism and Buddhism and all of them, but it was not to be found.

“They were classrooms I went through to learn what I need to know about me.

“The truth is that all of these religions started from Africa. The three monotheistic religions – Christianity, Judaism and Islam – all came from Abraham, he was a champion, and go right back into Egypt which is North Africa.”

And just as he searched for a faith, he also expanded the parameters of his music beyond ska and reggae.

He was a soul singer who explored those Jamaican idioms but also in that long career covered the Clash's Guns of Brixton, brought in samba and African rhythms and in '81 had a disco hit with Gone Clear.

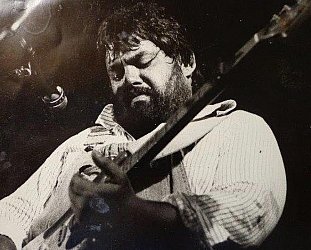

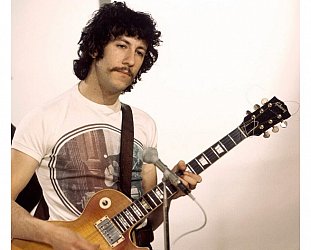

There are any number of decent Cliff albums (few of which have charted) and even more compilations, but Elsewhere has always had an affection for Special from ’82 where he was – in the hands of Rolling Stones engineer Chris Kimsey and with Stone Ron Wood on board – marrying reggae, rock, dancefloor and Jamaican roots-drumming.

In many ways Special – which is the soul-pop end of reggae and some distance from deep roots – was typical of Cliff's breadth.

In many ways Special – which is the soul-pop end of reggae and some distance from deep roots – was typical of Cliff's breadth.

His reputation meant he could conjure up great Jamaican players (Mikey Richards, Earl “Chinna” Smith, Ansel Collins, Sticky Thompson, Sly Dunbar and others) and amidst the pop direction he takes the album he also touches on issues close to his heart: Peace Officer, Treat the Youths Right, Roots Radical, Originator . . .

Yes, it suffers from the dreaded “Eighties production” and it plays its breezy weaker cuts up first in the title track and Love is All (where he sounds like he's in another room) but they are kinda catchy, especially the socio-political Love is All where the message comes through despite its lightweight sound.

After that it digs deeper with the more downbeat Peace Officer (“are you a warrior?”), Roots Radical written by Hardcase Spense is a hit in waiting even now (“I'm a roots radical, a true born Jamaican and I'm miles away from home”), Love Heights bridges light roots drumming and a cocktail hour band by the pool, and Originator brings in authentic nyabinghi drumming for a yearning piece of self-reflection as a genuine “originator”.

Certainly the production dates this and both Rock Children and the mainstream soul ballad Where There is Love deserved a more sensitive setting, but the material is there.

Cliff – who used Rasta imagery although not a follower – most often aimed for a wider audience than roots aficionados and because of its pop and dance inclinations (Keep on Dancing sounds a lightweight but he shoves a message into the groove) Special would never appear in any list of top 50 reggae albums. Perhaps Cliff's only entry would be the soundtrack to The Harder They Come.

But respecting great albums like the Congos' Heart of the Congos, Bunny Wailer's Blackheart Man, Burning Spear's Marcus Garvey and Social Living (and their dub editions) and a few by Marley, Lee Perry, Culture and Black Uhuru et al shouldn't preclude anyone enjoying this by the pioneer Jimmy Cliff, a star who arrived that fraction too early and was replaced by the more visible rebel presences of the Marley generation.

But Jimmy Cliff was one who just carried on doing his work – and many other things – in his lifetime.

.

You can hear Jimmy Cliff's Special on Spotify here

Elsewhere occasionally revisits albums -- classics sometimes, but more often oddities or overlooked albums by major artists -- and you can find a number of them starting here

post a comment