Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Texas-born and based Edie Brickell was 22 in '88 when – on a Saturday Night Live session in New York to promote this debut album with the New Bohemians – she first saw Paul Simon.

He was more than twice her age and enjoying global success (and some controversy) with the Graceland album . . . but troubling over a follow-up.

He was taken with Brickell's performance and music – and her personally – and their subsequent relationship meant the end of Simon being with actress Carrie Fisher, a relationship which been eroding away for a while.

Brickell was a talented writer, performer and an arts major and although her band had serious rock and jazz tastes (Robert Hilburn in his Simon biography mentions Miles Davis and the Grateful Dead) Brickell was more drawn to writers like Elvis Costello . . . and Paul Simon.

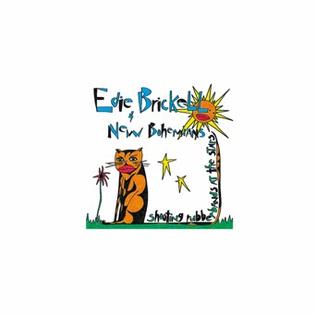

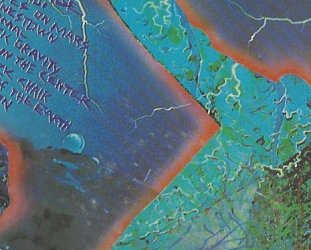

Her debut with the New Bohemians, Shooting Rubberbands at the Stars with her own art on the cover, sold more than two and half million copies, spurred on by the single What I Am (“is what I am. Are you what you are, or what?”)

Unfortunately their follow-up album Ghost of a Dog two years later didn't do quite so well (oh, just a paltry half million sold) but by that time Brickell was deep into her relationship with Simon and they would marry two years later at his home in Montauk.

Unfortunately their follow-up album Ghost of a Dog two years later didn't do quite so well (oh, just a paltry half million sold) but by that time Brickell was deep into her relationship with Simon and they would marry two years later at his home in Montauk.

The first of their three children was born later that year.

Brickell made a solo album in '94, Picture Perfect Morning which, despite good notices, all but disappeared when she wouldn't tour to support it.

She was happy being off the road, settled and domestic.

Home.

“I was seeing people who were older who didn't create any kind of foundation in their lives, and it scared me to death,” she would say.

“No matter how famous and established they were, with great songs or long careers, if they lived alone, they lived alone.

“That's not the way I wanted to live.”

And she hasn't.

She and Simon have been together more than 30 years and her solo career has been sporadic, notably recording with Steve Martin in recent years.

But Shooting Rubberbands at the Stars remains her finest and most endearing moment, a collection of smart, literate and wry songs which shift easily between folk, pop-rock (the flat-tack You Keep Coming Back with its shift into delicate bitterness) and folk-rock.

There was already a jaded worldview in Brickell, heard on the chiming but downbeat pop of Little Miss S who is “shooting up junk in the bathroom . . . living it up to die in the blink of the public eye”.

Brickell sings of the selfish indifference of those around a self-abusing and dying star: “It was the thing just to be by her side”.

Warhol's Factory or living in a Malibu mansion listening to the hissing of summer lawns was never going to be her home.

At times her lyrics have a similar compressed economy of a more sentimental and poetic Costello and Simon. As on Air of December: “In the by-myself mornings the birds windchime, the tree limbs crackle and the sunshine climbs in the sky like pink champagne . . . I swear I remember it that way, where are you now?”

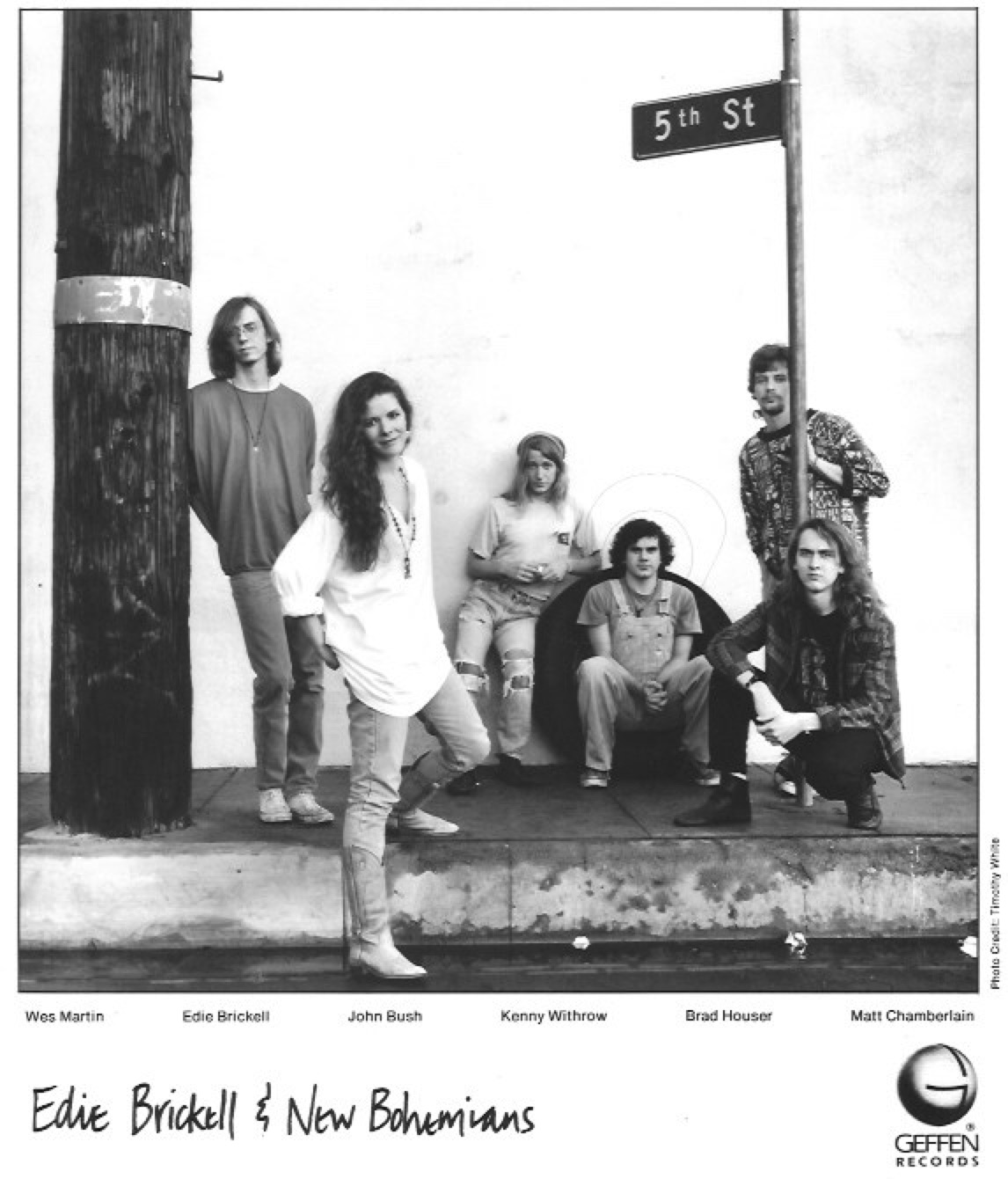

The songs are classy and clever in their arrangements. The New Bohemians of guitarist Kenny Withrow, bassist Brad Houser, drummers Chris Whitten and Brandon Aly (the former a year away from joining McCartney's touring band, the latter let go during the recording) and percussion player John Bush were all on the money . . . and were assisted by others including keyboard player Wix Wickens (also subsequently recruited into Macca's band).

The songs are classy and clever in their arrangements. The New Bohemians of guitarist Kenny Withrow, bassist Brad Houser, drummers Chris Whitten and Brandon Aly (the former a year away from joining McCartney's touring band, the latter let go during the recording) and percussion player John Bush were all on the money . . . and were assisted by others including keyboard player Wix Wickens (also subsequently recruited into Macca's band).

They can touch a kind of indie.rock and some upbeat folk-rock (Beat the Time).

Throughout the album the songs are strong and Brickell's delivery was just the right side of cynical (check Nothing, which betrays a reading of King Lear) and even edging towards optimism.

“I don't believe in hatred anymore” she sings on Love Like We Do, “I hate to think of how I felt before”.

The standout is the extraordinary Circles where she considers selfish companions and how being alone “is the best way to be, when I'm by myself nobody else can say 'goodbye' ”.

Everything is temporary anyway she notes, and then concludes “that's it, I quit, I give up, nothing's good enough for anybody else it seems”.

Everything is temporary anyway she notes, and then concludes “that's it, I quit, I give up, nothing's good enough for anybody else it seems”.

She captures that ennui which can exist within friendships and relationships.

And on She – a tune which could be delivered with a real sneer'n'thump but has more forgiving treatment -- Brickell works an interesting metaphor: “you can't judge her for that, she knows where her head is at . . . a house is not a home and a home is not a house when there's not enough room for you . . .”

She knew what she wanted: "I want someone to follow who doesn't lead the way . . . I'm filling in the negative space with positivity", she sings on the uncredited final track I Do.

Throughout Shooting Rubberbands at the Stars, Edie Brickell was aiming high and low, had found her voice and beliefs, and was poised for a mature and sensible acceptance of the well-balanced career which would doubtless follow.

And then she went in another direction.

Home.

.

You can hear Shooting Rubberbands at the Stars on Spotify here.

.

Elsewhere occasionally revisits albums -- classics sometimes, but more often oddities, or overlooked albums by major artists -- and you can find a number of them starting here

post a comment