Graham Reid | | 5 min read

In 1961, the blues singer Albert Hunter – who'd been born at the end of the 19thcentury and had recorded with Fletcher Henderson, Fats Waller, Louis Armstrong, Eubie Blake and many others – went into Rudi Van Gelder's studio to record with Victoria Spivey and Lucille Hegamin for the Prestige label.

It was the first time she'd been in a studio in almost 20 years.

She was 67 at the time and the subsequent album was tellingly entitled Songs We Taught Your Mother.

But the short session was so successful that producer Chris Albertson – author of biography of Hunter's friend Bessie Smith who'd launched to fame on the back of Hunter's classic Downhearted Blues – persuaded her to stop off in Chicago to record an album under her own name when she was on her way for a holiday in California.

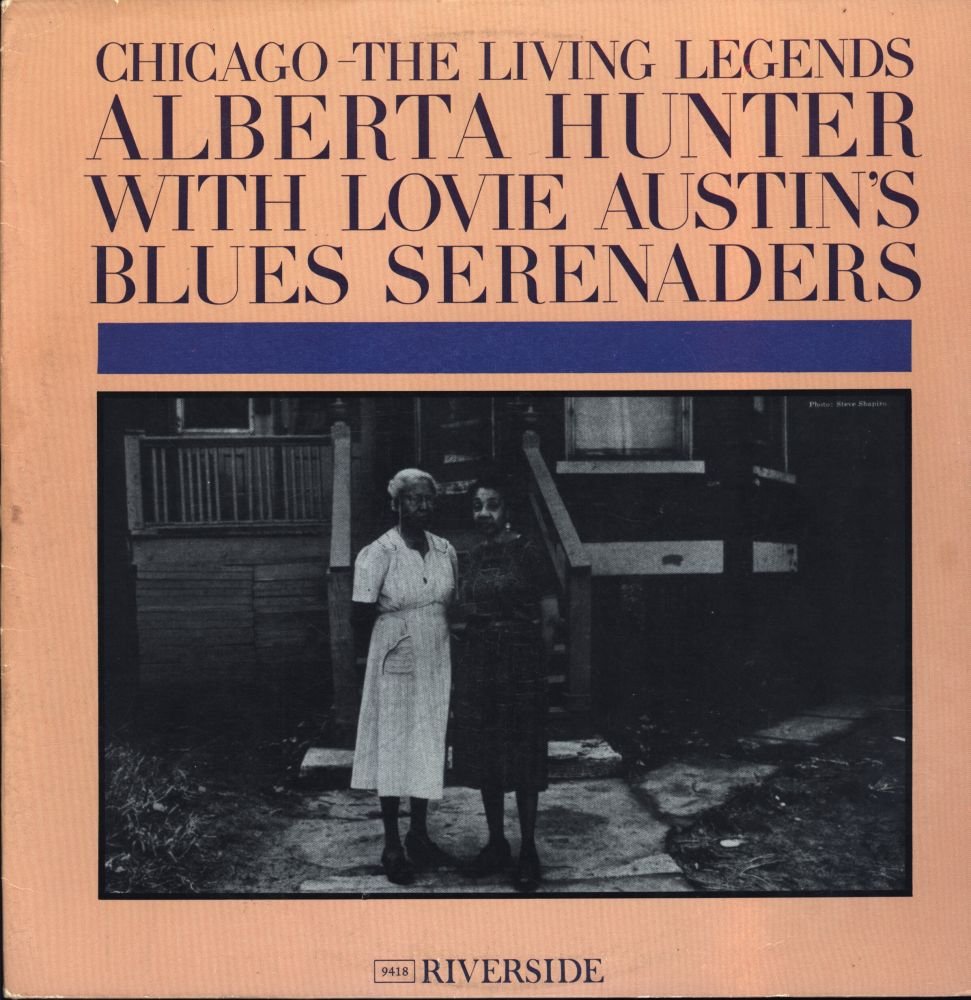

The bait he offered was reuniting Hunter with pianist and old friend Lovie Austin, and Lovie's quartet.

That album, recorded in an upstairs room in the Prince Hall Masonic Temple, was done in just a few hours with Hunter laying down eight songs (seven appeared on the album, Downhearted Blues among them) before she rushed off to her train.

That album, recorded in an upstairs room in the Prince Hall Masonic Temple, was done in just a few hours with Hunter laying down eight songs (seven appeared on the album, Downhearted Blues among them) before she rushed off to her train.

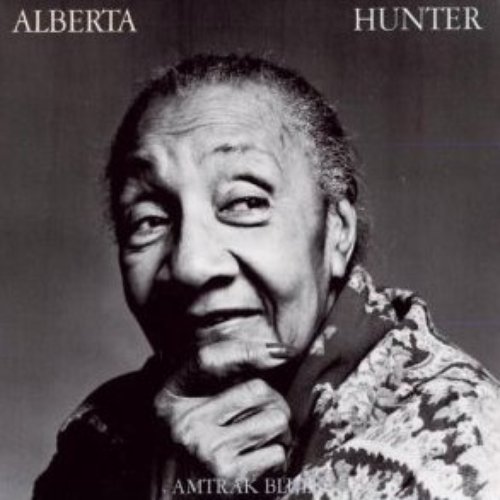

It would be almost 20 years before she would record again, persuaded then to do so by Columbia's John Hammond for the album Amtrak Blues.

And then, in her early Eighties, the great, quick-witted, astute and exceptionally talented blues singer Hunter enjoyed a third career.

With Amtrak Blues there were stories in Rolling Stone, a full page in Time, reviews around the world (although the Auckland Star called the album Australia Blues) and she was widely interviewed because . . .

Alberta Hunter had a story to tell about a life born on Beale Street in Memphis, heading to Chicago to make money when she was 10 (“not because of treatment but because I had ambition”), getting a chance to sing at Dago Frank's saloon which was hangout for pimps and prostitutes, hooking up with Armstrong, King Oliver and others, starting to write her own songs, touring in Europe . . .

It was a life which now reads like a movie script dotted with cameos of every great black blues and jazz artist before the Second World War.

It was a life which now reads like a movie script dotted with cameos of every great black blues and jazz artist before the Second World War.

But when her mother died in '54 Hunter quit music and decided to make a contribution to the world so -- lying about her age by dropping 12 years -- she trained as a nurse and worked, until she was forced to retire at “70”, at the Goldwater Memorial Hospital in New York.

It was during that time she was persuaded by Albertson to record with Spivey and Hegamin for a Chicago Living Legends album on Riverside.

And then the subsequent album Alberta Hunter with Lovie Austin and Her Blues Serenaders.

Most people -- outside of blues and jazz aficionados -- caught the Hunter revival in the early Eighties with three acclaimed (if disappointing selling albums) on Columbia when all that publicity was happening . . . . and when she was apparently earning $US10,000 a night, but still making time to visit patients in the Goldwater.

Alberta Hunter was remarkable women with an equally extraordinary life in and out of music.

Before her death in '84 at age 89 that album recorded in Chicago so many decades previous, was reissued. And it is like a journey back through time to the Twenties and Thirties.

She, Austin and the band open with WC Handy's St Louis Blues, pick up the classic Moanin' Low and her originals Downhearted Blues, Now I'm Satisfied, You Better Change and Streets Paved with Gold.

She, Austin and the band open with WC Handy's St Louis Blues, pick up the classic Moanin' Low and her originals Downhearted Blues, Now I'm Satisfied, You Better Change and Streets Paved with Gold.

Right at the end is the wonderful ballad I Will Always Be in Love With You delivered with power and real bite.

Hunter sits some songs out (or was on her way to the train?) so there are three instrumentals by Austin – who co-wrote Downhearted Blues with Hunter – and her band (Sweet Georgia Brown, Ellington's C Jam Blues and Austin's original Gallion Stomp).

Austin's musicians were members of Earl Hines' band.

Think about that . . . and say, "Wow!"

Albert Hunter -- a lesbian who kept her private life to herself -- was part of a generation which was rapidly disappearing and memories were all these artists had to share. And the songs, of course.

During the sessions, according to Albertson's original liner notes, she would tell stories like how she and Bessie Smith would sneak through the alley to hear Ma Rainey [to her, Gertrude] sing.

“We were too young to get in [to the club] but Gertrude's voice was mighty powerful and Bessie used to sing along with it.”

Austin, 74 at the time of these '61 session, had accompanied – among many others – Ma Rainey and Ida Cox.

So neither Hunter nor Austin (or the musicians) were recreating something, they were singing the songs they knew first hand.

Many people will be familiar with the later albums when Hunter enjoyed her third life as a recording artist, but those Columbia albums – with her voice more burnished and deeper and arguably warmer with age – came from a very different time as the session in '61 with Austin.

Many people will be familiar with the later albums when Hunter enjoyed her third life as a recording artist, but those Columbia albums – with her voice more burnished and deeper and arguably warmer with age – came from a very different time as the session in '61 with Austin.

By the Eighties old blues and jazz had been rescued from the archives, was being reissued on labels like Columbia Legacy (which re-presented the complete Bessie Smith recordings) and RCA Bluebird (the complete Fats Waller over a series of double albums).

Pre-war jazz and blues had become much more familiar.

But in 1961 when the Hunter/Austin album was recorded, jazz was no longer bordello music and was being played in sophisticated clubs and concert halls.

However the blues had yet to undergo any major resurgence of interest. The influential Robert Johnson compilation King of the Delta Blues, for example, was released that same year . . .but its impact had yet to be heard.

And when the blues enjoyed a revival it was mostly from Chicago and electric, and came with a British accent and guitar heroes.

Hunter (who never smoked nor drank) and Austin went back much further. They were from a time before the war which was really only available on 78rpm and a few cobbled together compilations in '61.

So this album was a courageous undertaking for Riverside and producer Albertson, because there was no established audience for it.

The blend of hurtin' blues (St Louis Blues, Moanin' Low), the spiritual (Hunter's salvation song Now I'm Satisfied and the gospel strut of You Better Change), humour (Sweet Georgia Brown, C Jam Blues) and hope (Streets Paved with Gold) belonged to a more distant time.

This was secular entertainment . . . and with a spiritual uplift.

Those sentiments -- and the musical and voices on this album -- are timeless.

.

You can hear this album on Spotify here and Hunter's much earlier recordings-- as well as Amtrak Blues -- are there too.

.

Albums considered in this on-going page of essays are pulled from the shelves at random, so we can get the good, the bad or the indifferent from major artists to cult acts and sometimes perverse oddities.

Kelvin Roy - Aug 10, 2020

Good reprise... I remember enjoying listening to her, particularly the newer, but happy to see you're pointing her out (again)

SaveMike P - Feb 20, 2024

I have both of the two albums that you show and another called look for the Silver lining. Alberta has been a favorite of mine for quite a number of years. If I start off an evening listening to Alberta, then this tends to bring on a female blues listening session, for the rest of the evening.

Savepost a comment