Graham Reid | | 4 min read

First of all, you have to remember the period in which this album by saxophonist Oliver Lake arrived: Wynton Marsalis was making his career run on the back of his neo-conservative stance (hailing Ellington and early Miles, dismissing post-bop, fusion and free jazz etc) and in his corner he had the bullish critic and cheerleader Stanley Crouch.

Marsalis being articulate, sharp, handsome and signed to Sony was the star ascendant and Miles Davis with his urban funk on albums like Star People, Decoy and You're Under Arrest wasn't selling.

Alongside Marsalis came fellow travelers like pianists Marcus Roberts and Kenny Kirkland, and drummer Jeff Watts. And on his debut, Marsalis had legends like Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams, all of whom had been with Miles in his great period which Marsalis referenced and revered.

That was seemingly the musical and intellectual battleground for the soul of jazz . . . but away from the fray the likes of Ornette Coleman, bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma, guitarists John Scofield and James Blood Ulmer, and others just carried on indifferent to the debate.

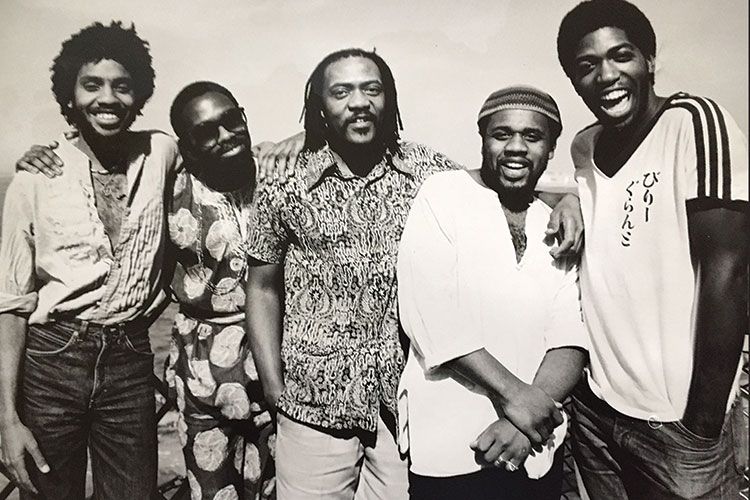

And Lake -- who boasted dreadlocks, brought in a touch of reggae, had come out of the World Saxophone Quartet and at the time was releasing albums on the emerging Gramavision label and the cutting-edge Black Saint out of Italy (Archie Shepp, Enrico Rava, Hamiet Bluiett, Lester Bowie and others).

And Lake -- who boasted dreadlocks, brought in a touch of reggae, had come out of the World Saxophone Quartet and at the time was releasing albums on the emerging Gramavision label and the cutting-edge Black Saint out of Italy (Archie Shepp, Enrico Rava, Hamiet Bluiett, Lester Bowie and others).

So Lake and his band Jump Up were outliers with funk, reggae, synths and Lake's vocals (which were often pretty lame even if his lyrics were kinda cool).

This album – and its not dissimilar self-titled predecessor Jump Up – pulled from the shelves at random for consideration was one that got him a couple of pages coverage in Downbeat, in part because he was pulling the non-jazz punters for his danceable musical meltdown.

As Bill Milkowski noted in that Downbeat article of May '83, those drawn to the band at Sweet Basil's in Greenwich Village – tourists, clubbers and passersby – were “instantly riveted to the driving reggae-funk groove. Within moments their bodies are moving, lost in the hypnotic pulse of chicken-scratch rhythm guitars and lazy booming bass”.

And on the stage was Lake in a multi-coloured costume tossing his dreadlocks and singing “one foot guides the other” from their Jump Up debut.

As with so many of the more interesting artists outside the straitjacket of neo-conservatism at the time, Lake spoke of how all the music he had played – World Saxophone Quartet stuff, backing r'n'b singer like Rufus Thomas and Solomon Burke, avant-garde or working with the Kronos Quartet, Afro-Caribbean music, reggae and funk – were all part of the same thread and continuum of great black music.

As with so many of the more interesting artists outside the straitjacket of neo-conservatism at the time, Lake spoke of how all the music he had played – World Saxophone Quartet stuff, backing r'n'b singer like Rufus Thomas and Solomon Burke, avant-garde or working with the Kronos Quartet, Afro-Caribbean music, reggae and funk – were all part of the same thread and continuum of great black music.

He'd played in various parts of Africa with Jump Up and the idea of dance and singing was embedded in most of the music he'd loved, whether it be jazz or more commercial music.

Like his friend Lester Bowie – who bubbled through a straw in water and called it Miles Davis Meets Donald Duck, and played Michael Jackson's Thriller with a brass ensemble – Lake had a sense of humour and enjoyed the fun aspects of making music.

That comes through on Plug It which, while not a great jazz-funk album certainly has the desired effect. It's hard not to dance to.

In Tone Clone the women sing “slippery edged sonority focused through bar lines and measures . . . .” and Plug It's lyrics consist solely of “You take it and you plug it, you work it . . . colour TV, colour TV, yeah!”

And why not?

When Lake sings at times he sounds closer to Sly Stone than any male singer of the broad jazz spectrum and in fact his sonic palette – with electric guitars and bass by Jerome Harris and Brandon Ross – the Jump Up band is more akin to Sly with Talking Heads (Breath of Life). They just needed a more pushy and punchy producer to bring the funk more to the fore.

You'd love to hear a dubby remix of some of the songs on Plug It (such as Go For It).

Oliver Lake had a long career before the Jump Up band (three albums in the Eighties) and after (collaborations with Bjork, Lou Reed, A Tribe Called Quest, Mos Def and many, many others).

At the time of this writing he's 78.

He could be as snappy and a distinctive dresser as Ornette Coleman, received a Guggenheim Fellowship and more awards than you can easily count and has been one of the most consistently interesting, shapeshifting jazz musicians of the our time.

He could be as snappy and a distinctive dresser as Ornette Coleman, received a Guggenheim Fellowship and more awards than you can easily count and has been one of the most consistently interesting, shapeshifting jazz musicians of the our time.

Not always successful, and largely off the radar outside of Black America jazz aficionados perhaps but . . .

Although the second side here takes a more serious Johnny Clegg turn with the closing track No More War (“just for profit, we've got children to feed”) this is an album to discover.

If you can find it – it's not on Spotify or iTunes as far as I can see – but it's worth locating in secondhand stores.

If you do – especially on side one – you may well find yourself instantly riveted to the driving reggae-funk groove and within moments your body moving, lost in the hypnotic pulse of chicken-scratch rhythm guitars and lazy booming bass.

Life could be worse.

.

Elsewhere occasionally revisits albums -- classics sometimes, but more often oddities or overlooked albums by major artists -- and you can find a number of them starting here

post a comment