Graham Reid | | 3 min read

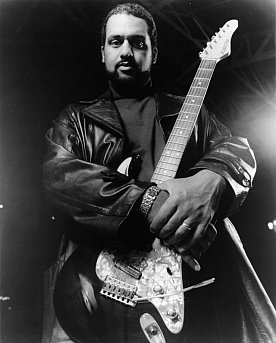

In an interview with Elsewhere some years ago, Vernon Reid of the seminal black rock band Living Colour observed that once they got through the door of the hierarchy of the white rock critical community the access for other black rock bands slammed shut behind them.

It was like, “We'll we've got our black rock band, why would we need another?”

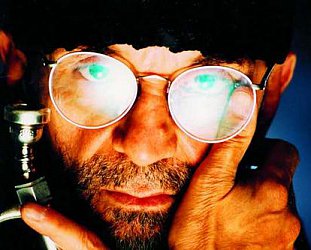

Something similar happened in the post-Hendrix avant-guitar generation.

Once James Blood Ulmer was accepted as a free jazz successor to Hendrix's more extreme playing, the door shut on the likes of Jean-Paul Bourelly.

Ulmer came with serious jazz credentials – time with Art Blakey, Ornette Coleman and Arthur Blythe among them – but then so did Bourelly who was two decades younger.

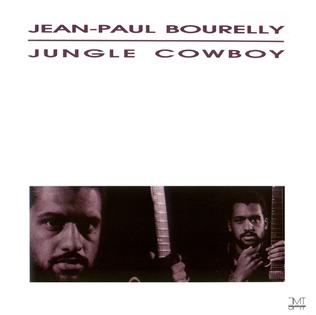

By the time of this debut album under his own name – which we have pulled from the shelf at random to consider – the Chicago-born Bourelly had grown up on the blues and lyric opera (the first by assimilation, the second by his mother pushing him there when he was 10) but in an interview with Option magazine spoke of Muddy, Jimi, Sly and James Brown in the same breath as Cream, Coltrane, Miles and the Beatles' I Am the Walrus.

By the time of this debut album under his own name – which we have pulled from the shelf at random to consider – the Chicago-born Bourelly had grown up on the blues and lyric opera (the first by assimilation, the second by his mother pushing him there when he was 10) but in an interview with Option magazine spoke of Muddy, Jimi, Sly and James Brown in the same breath as Cream, Coltrane, Miles and the Beatles' I Am the Walrus.

From his family background – Haitian, French – he gravitated to Yoruban music through his grandmother and Afro-Cuban sounds – but then became deeply assimilated in jazz.

He learned piano and drums, moved to guitar, played with Von Freeman (father of Chico), shared space with M-Bass founder Steve Coleman when he moved to New York where he recorded with pianist Muhal Richard Abrams, played with Elvin Jones where he extended his guitar style, McCoy Tyner, Pharoah Sanders, avant-garde players like Henry Threadgill and . . .

You'd think he was well through the door which had been opened by Ulmer just a few years before.

But while Ulmer was signed to Columbia in the US, Bourelly had to be content with the new German label JMT for his debut recorded in New York in late '86.

The album had a lot going for it in terms of players: altoist Julius Hemphill and drummer Andrew Cyrille from the AACM avant-garde, bassist Freddie Cash, r'n'b singer Alyson Williams . . .

Aside from the nine originals they also covered Memphis Slim's Mother Earth.

But the jury was divided.

Some couldn't have hated it more and wrote him off as a lesser Hendrix, others in retrospect hailed it as his best album (which may of course say something about all the others, of which there have been many).

Musicians however respected him – the following year he played on Miles Davis' Amandla and over the years worked with Vernon Reid, Jack Bruce, Cassandra Wilson, Marc Ribot, Jamaaladeen Tacuma . . .

So, listened to now, does Jungle Cowboy stack up?

It is certainly inconsistent – a showcase debut, perhaps? – but on the high energy Love Line and No Time to Share which stutter and stagger like Ulmer, and the urgent funk driven by drummer K-Dog Johnson and bassist Cash (Tryin' To Get Over with the Jimi and Ulmer influence evident) there is some real spark and fire here.

Surprisingly Hemphill is somewhat restrained in this neo-funk/rock context (the rather pleasant Drifter) yet those more moody pieces – especially Mother Earth – are among the uneven album's better moments.

Parade is a fairly straightforward intrumental blues with his distinctive twist which leads into Mother Earth.

Certainly the spirit of Jimi/Ulmer is evident in many places here, notably on the too-short title track where Hemphill really lets go and shoves it into fresh and furious avant-funk territory.

What pulls it back are the shapeless songs (the sub-Sly Can't Get Enough) and Bourelly's weak vocals in the few – but too many – places where he sings. He lacks the distinctiveness of Jimi or Ulmer, and often sounds breathless and hurried as he tries to get his lines in around the jazz-funk, and lacks expression on the ballad Hope Your Find Your Way.

You can hear why so many were down on it at the time, however it's worth remembering that Ulmer was the star turn in the avant-garde at the time and everywhere else the neo-conservative movement helmed by Wynton Marsalis and his bullying champion Stanley Crouch was silencing any progressive music.

Listened to alongside some the less adventurous jazz and funk from this period, it has at least that virtue of making an effort.

But as we know, trying hard just isn't enough.

.

Unfortunately this album isn't on Spotify or Apple iTunes although a number of his later albums are, including his Hendrix tribute.

.

Elsewhere occasionally revisits albums -- classics sometimes, but more often oddities or overlooked albums by major artists -- and you can find a number of them starting here.

post a comment