Graham Reid | | 6 min read

John Mayall: The Death of JB Lenoir (from Crusade, 1967, with guitarist Mick Taylor)

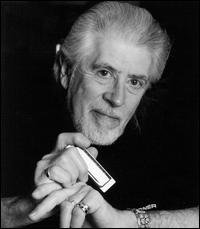

The English musician John Mayall repeats his familiar refrain: he’s never had “a hit record, never won and Grammy and isn’t in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame“.

At 76 and having played professionally for more than 45 years he might have reasonably expected one or more of those. But in 2005 he did get an OBE.

“That was a total surprise,” he laughs. “You think maybe a gold record might happen, some kind of recognition in that department. But for it to come from Buckingham Palace was quite another thing. Amazing.

“It was recognition by my country that I had been of service. That overshadows being in the hit parade.”

There is an irony here: The service Mayall had done was for the music he loved since childhood: American blues.

In the British blues boom of the 60s, Mayall name is written large.

During a brief period his revolving-door Bluesbreakers band was home to guitarists Eric Clapton, Peter Green (in early Fleetwood Mac) and Mick Taylor (subsequently a Rolling Stone), bassists John McVie (a co-founder of Fleetwood Mac) and Jack Bruce (later in Cream with Clapton) and many other luminaries in British rock.

Mayall’s bands down the decades have been a supportive environment for all kinds of talent: he always had an instinct for great guitarists and in the 80s had the exceptional Coco Montoya, today it is tough Texas player Rocky Athas (whose finger-tapping style influenced Queen‘s Brian May and was allegedly the subject of Thin Lizzy‘s Cocky Rocky in ‘76).

But for many it was that fruitful and vibrant period of the 60s which was the most interesting and exciting of Mayall‘s long career.

This was a time of discovery of black blues in the absence of much information: records were hard to come by, there were few books and the artists were somewhere in America. Yet a generation of young British musicians discovered something in the music which spoke to them, and the people followed.

“There was a magic of discovery by the general public in England. For the previous 10 years people had been listening to trad jazz -- Humphrey Lyttelton, Chris Barber and Kenny Ball, those great bands. But that wore itself out and there was this new thing and a new generation, who hadn’t been into jazz, discovered electric guitars and the excitement of blues.

“It exploded rather than crept up. People like Alexis Korner and Cyril Davis got the whole thing together and before you knew it there were all these young groups forming. That included of course the Rolling Stones and many others. It was an exciting and unique time.”

Mayall, being a decade older than most and something of a mentor, didn’t become a professional musician until he was 30 and had a decent career in advertising as a graphic artist and sometime painter. One of his band portraits was the cover of his ’67 Bluesbreakers album A Hard Road.

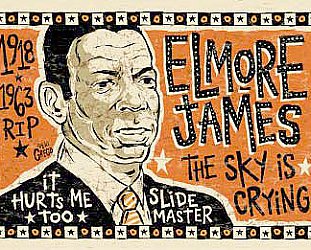

But he had taught himself piano and guitar, loved the raw sound of black artists such as Leadbelly and J.B. Lenoir, and he had played semi-professionally in a number of bands around Manchester.

In ‘62 -- encouraged by Korner -- he quit the day job, moved to London, started the Bluesbreakers, and by the late 60s was renown as a talent spotter and influential player on the British blues scene. A trip to the United States saw him change direction, and not long after relocate to Los Angeles where he has lived since.

His autobiographical ‘68 album Blues From Laurel Canyon was recorded after a three weeks “life-changing” experience with American musicians and in the heady hippie-era in Los Angeles. Given he was American by musical inclination, the shift was inevitable. It offered him the opportunity to work with his heroes (he produced Albert King) but also, more prosaically he admits, “the weather was better“.

“At the time I left England the blues environment was still thriving and it wasn’t until the 70s kicked in that the wave had passed by. But by then I had already gone.”

Mayall’s life changed by being in the US: his profile in Britain declined as the blues fell from favour, and there was a period between 1969 and the mid 70s when every album sounded different: He explored the idea of drummer less trio (The Turning Point of ’69); reconnected on record with members of Canned Heat whom he’d met on that pivotal vacation (USA Union, 70) and notably worked with jazz musicians like trumpeter Blue Mitchell and saxophonist Ernie Watts.

Record sales suggested he was shedding his original audience although he remained a significant live attraction playing hundreds of nights a year and always enjoyed a core of support.

“I had total confidence that audiences everywhere would trust my judgement and were there to enjoy whatever I came up with, and that is still true today.”

Mayall -- although never the strongest of singers whose adenoidal vocals can be as annoying as they are affecting -- kept abreast by writing autobiographical songs or reflecting on contemporary issues, something he still does. Songs on his Tough album of last year deal with the economic recession. For him the blues was never a dead, archival music.

“The blues should be relevant to your own time and that would apply to current events, your life, and things familiar to you.

“I shouldn’t be singing about cotton fields, that’s not a part of my heritage. All the major blues players have sung about what has happened to them in their lives and environment, and that’s the tradition I hope to keep alive.”

He is aware his chosen music enjoys waves of popularity -- the rise of George Thorogood, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Robert Cray, artists on the Fat Possum label and most recently the Martin Scorsese television series The Blues -- but they exist independent of him. Although they raise awareness of the blues, none have affected attendances at his shows, which average around 100 a year.

“I’m still pretty much of an underground figure,” he says then repeats that familiar, slightly aggrieved refrain.

“The advantage of having a hit record is it increases your audience potential. The downside, which I don’t think would affect what I do because I’m famous for being different, is it would lock you into something and you have to play that for the rest of your life.

“But I’ve always had the freedom to do exactly what I want musically and never had any interference or pressures from outside influences. You can’t beat that.”

These days he tours with yet another line-up where he plays piano and fiery Jimmy Smith-style organ: “It’s very hit and miss. I only come to life when I’m playing with other people. Every night is an excursion into the unknown.”

And the man who never learned to read or write music now has 57 albums under his belt?

“That doesn’t take into consideration the legions of compilations put out by different record companies, the “best of” albums and things I don’t count.

“But yes, 57 individual albums. So far.”

JOHN MAYALL

CIVIC THEATRE, AUCKLAND

APRIL 2010

John Mayall is a rare one. Few artists

– unless they have had huge hits and a high profile, and Mayall has

never had either – could pull an audience on the strength of a name

and reputation alone. And even fewer would be in the lobby selling

their most recent CD and cheerfully shaking hands (even with those

weren't buying) while the support act – in this case Hammond Gamble

– warmed the crowd.

But there was Mayall – thick white

hair in a ponytail – meeting his fans, many of whom probably didn't

know there was a new album, or had even bought a Mayall album since

the 60s when this legendary blues musician (keyboards, harmonica,

vocals), was at peak profile.

And Mayall acknowledged that knowledge

gap in an almost two hour set which ignored the four decades between

“the Clapton Beano album” (the Bluesbreakers album

of 66) and The Turning Point of 69 (a crowd pleasing Room

to Move) to last year's Tough.

With a well-honed band which

unfortunately rarely allowed Texas guitarist Rocky Athas sting and

soar as he can -- and had him literally out of the spotlight –

Mayall was a genial and hard working frontman. Whether it be nodding

back to familiar material (All Your Love, Have You Ever Loved A

Woman, Checking on My Baby, Parchman Farm, Pretty Woman – a

tick-list from his heyday) or laughing when he started on harmonica

in the wrong key.

At its best – the sultry jazz-blues

of an extended California, the enjoyable interplay with Athas

on Pretty Woman and with

keyboard player Tom

Canning in places,

bassist Greg Rzab throwing in

some Stanley Clarke funk and a snatch of Hendrix's Third

Stone from the Sun – this was

occasionally terrific.

But Mayall's vocal expression has

always been limited, there was perhaps too much harmonica blues and

better material on Tough to showcase than Nothing To Do

With Love, and with Athas seldom off the leash to really build a

solo, this was also a concert which was enjoyable rather than

exciting, one which delivered rather than took flight.

But at 76, John Mayall – who looked

in remarkable, cheerful condition -- remains a rare one.

.

John Mayall died in July 2024. He was 90.

.

Like this? Then check out the interviews, reviews and overviews at Blues in Elsewhere.

post a comment