Graham Reid | | 3 min read

All Your Love

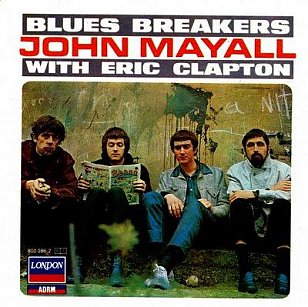

For an album which is a cornerstone in any serious consideration of the British blues boom of the Sixties, the Blues Breakers record -- John Mayall with Eric Clapton -- of July '66 hardly had an auspicious gestation.

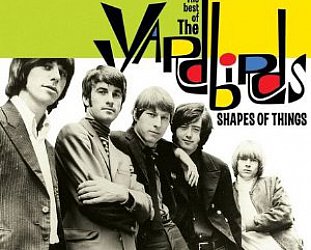

In March '65 Mayall and the Blues Breakers had been dropped by their label Decca after just one album (a live outing, John Mayall Plays John Mayall) and across on the other side of the music spectrum at the same time guitarist Eric Clapton had quit the Yardbirds because of their move towards a more pop sound.

These two stateless figures -- Mayall at 32 some 12 years older than Clapton -- gravitated towards each other -- and a deeper kind of blues -- at exactly the same time as British pop was reaching a zenith.

The Beatles' Help! pop-frippery was just around the corner; the Stones' singles The Last Time and Satisfaction secured their position globally; and the Animals, Kinks, Walker Brothers (from America) and dozens of others created an atmosphere of upbeat and Swinging London . . .

It was Op Art, Pop Art, Carnaby Street, Twiggy . . . the full Austin Powers.

And off on the side was the darker sound of the blues which, although providing the foundation for the Animals and Stones, was being rapidly left behind by them in favour of chart success.

So when Mayall, the Blues Breakers (which included bassist John McVie later of Fleetwood Mac and drummer Hughie Flint) got together with the earnest Clapton there was no reason to expect that they might make an album which -- even today -- sounds fresh, vital and edgy.

Indeed Clapton had joined the band then quit after a few months, taken off to Greece, then re-joined in November. Hardly a promising start.

As Clapton sought to find out how to make the harder sound of Chicago blues players -- he bought a secondhand Les Paul Sunburst and hooked up to Marshall amps -- the band took to road and tightened up. Jimmy Page produced a single I'm You Witchdoctor (which appeared on Andrew Loog Oldham's Immediate label, alongside the Small Faces) and as a result producer Mike Vernon persuaded Decca to re-sign them.

Then Vernon took them into the studio and captured them as the raw, live act that they were with Clapton's stinging guitar given prominence.

Clapton hadn't abandoned his pop smarts learned in the Yardbirds entirely -- there is sharp economy in his playing . . . and he even quotes the Beatles' Daytripper in their workout on Ray Charles' What Did I Say.

But his sound is so brittle, dry, dirty even and undeniably powerful that the album set itself apart from whatever else was out there. And the music was tough and adult -- material drawn from Otis Rush/Willie Dixon (All Your Love with its kicking time change), Robert Johnson (Ramblin' on My Mind on which Clapton took his first lead vocal), Freddie King (Hideaway) and Little Walter (It Ain't Right) alongside some Mayall originals in the genre.

"We had no trouble selecting what would go on it," said Mayall later. "It was just what we were doing in our set."

And in many places the album sounds closer to the pub-rock of Dr Feelgood a decade later than the pop or pre-rock of Swinging London.

It was one of the greatest -- if not the greatest -- albums of the British blues boom, and the one which set in motion the rise of the guitar hero.

It was one of the greatest -- if not the greatest -- albums of the British blues boom, and the one which set in motion the rise of the guitar hero.

The music on "the Beano album" as it is sometimes known (for Clapton reading that rebel kids' comic on the cover) has endured, and the cover become so iconic it is referenced and respectfully parodied.

Even today on Mayall's tours he draws on it for much of his set -- and refers to it as "the Beano album" as if to remind older heads.

Not that they need much reminding, the music -- sharp as broken glass -- cuts through time.

It was also a one-off which doubtless enhances its allure: by the time it fell off the British charts after a 17 week run (peaking at #6), Clapton had already moved on.

He stepped out the door and hooked up with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker to form Cream -- but the door never fully closed . . .

After Clapton's departure Mayall took the band to a different plateau with guitarist Peter Green (again, he'd taken over when Clapton went to Greece), Fleetwood Mac formed as a blues band, and Clapton's American guitar heroes like Buddy Guy started to have a viable second life in Britain.

The most significant chapter of the blues in Britain both began and ended with this exceptional album.

And the Beano never had better publicity.

.

John Mayall died in July 2024. He was 90.

.

These Essential Elsewhere pages deliberately point to albums which you might not have thought of, or have even heard . . .

But they might just open a door into a new kind of music, or an artist you didn't know of. Or someone you may have thought was just plain boring.

But here is the way into a new/interesting/different music . . .

Jump in.

The deep end won't be out of your depth . . .

Like this? Then check out the interviews, reviews and overviews at Blues in Elsewhere.

Peggy in America - Feb 7, 2022

It's interesting that a lot of people seem to have a personal opinion of Mr. Mayall. Embracing, or dismissive, its it's own tale, and a quick question, or an abrupt "I Saw Them!!!" comment often tells you more of them, than him. But then -- he's like that, isn't he? Truly, the imp of impetus.

SaveGraham Dunster - Aug 1, 2024

Agree re the Beano lp, have to say that the early Fleetwood Mac records were pretty damn good too. (Dandy, perhaps?) And what is with the illustration you've used in place of the lp? Looked at their Bandcamp page and listened to their music but....!

Savepost a comment