Graham Reid | | 9 min read

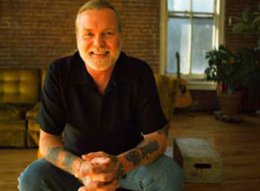

Gregg Allman: Floating Bridge

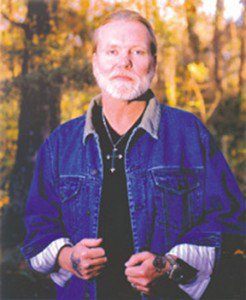

Scroll down the Wikipedia entry for Gregg Allman and two things will surprise: first how brief it is for a musician who has lived such a full, creative and often dangerously self-abusive life.

And second the interestingly inexact sentence

which reads, “Allman has been married at least six times . . .”

By the time he was 30, keyboard player

and guitarist Allman – now 63, one of rock's great Southern

soul-blues voices and the co-founder of the legendary Allman Brothers

Band with his guitarist/brother Duane – had done enough to fill a

few lifetimes.

By 77 he'd been married twice

previously and was hitched to Cher; had delivered the classic ABB

live album At Fillmore East, buried Duane who had been killed

in a motorcycle accident just months after the Fillmore shows,

reformed the band then a week later had buried bassist Berry Oakley

killed in an eerily similar accident a year after Duane, fallen out

with the band after he'd testified against his friend and road

manager in drugs trial (“There is no way we can tour with with Gregg

Allman again, ever,” said guitarist Dickey Betts) and was battling

various addictions.

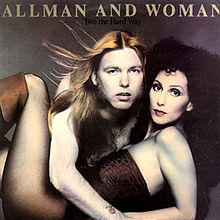

His album with Cher of that year –

Two the Hard Way, credited to “Allman and Woman” – is

widely considered a career low for both artists. On e-Bay recently an

unopened vinyl album was 10 times more than a previously-played copy.

His album with Cher of that year –

Two the Hard Way, credited to “Allman and Woman” – is

widely considered a career low for both artists. On e-Bay recently an

unopened vinyl album was 10 times more than a previously-played copy.

And Allman did all that before he was

30.

And even last year was colourful: he

recorded his first solo album in 14 years, played a few solo shows

and had a liver transplant after years of suffering years the

debilitating effects of Hepatitis C and Interferon treatment.

That Gregg Allman is here at all after

decades of serious drugs and alcohol is surprising, that he is lucid,

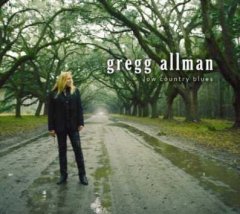

good-humoured and that the album Low Country Blues is so good

seems a bonus.

In fact, much as the new album – a

collection of T Bone Burnett-produced blues songs with Dr John and

others in the tight band – is worth a conversation, but Allman

speaks most about that “glorious moment” of clarity in 95 when he

knew he had to clean up for good.

“Well, it wasn't too glorious,” he

says in a croaking Southern drawl and sounding every minute his

years. “It was glorious in that there was light. It was when we got

the award for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and I saw a DVD of it

the next day and, 'Ooh God'.

“I'd promised myself I was not going

to get all saucer-eyed, it wasn't going to happen and me look like

some old wino. So I had measured out lines in the hotel room at the

Waldorf Astoria and I would just hit one each hour to keep the shakes

off, but I won't get blotched.

“So I went downstairs for something

and saw just about everyone in the music business I hadn't seen in

about 20 years and they are like 'C'mon on the bar and have a few

pops'. My mistake.

“By the time I got to the stage to

receive the honour I didn't think I could climb the steps. The rest

of the guys in the band were holding their breath. I saw the film the

next day and stopped smoking, stopped marijuana, stopped booze,

stopped injecting, I stopped it all. Every single thing: nothing but

air, food and water.

“And I don't even hardly remember it,

man. I remember I hired a male nurse to come in and give me

electrolytes and vitamins to put back in the body and he was there

for a little over a week. I detoxed down and he gave me something to

sleep with.

“When he left I felt like hell for

about another week and then one morning I felt good again. I actually

wanted to get out and do something. I was able to drive my car and

ride my motorcycle too. I thought, 'This is really fun, man'.”

Allman says addicts find their glorious

moment in many ways: ”For some people it's when they hit bottom,

for some it when the doctor tells you, 'Hey man, you're gonna die',

or you see your own baby for the first time. A whole bunch of

different things.”

For him it was screwing up in front of

important people in his life: “That was the biggest part. I wanted

to say things about [Fillmore owner and promoter] Bill Graham, about

my mother, something about everybody who got me to that place where I

was right then. And I just said, 'This is for my brother' and walked

off.

“Later I thought, 'You cheap shit'. I

was terribly pissed off at myself. But it was also the best thing

that could have happened to me.”

As a man steeped in the lives and

stories of old bluesmen and then living the rock'n'roll lifestyle of

excess, did he ever justify to himself that what he was doing was

somehow just what musicians do, providing the raw material of life?

As a man steeped in the lives and

stories of old bluesmen and then living the rock'n'roll lifestyle of

excess, did he ever justify to himself that what he was doing was

somehow just what musicians do, providing the raw material of life?

“Not really, I pretty much give up

for everything I've done. I definitely had an addiction and that

would screw anybody's life up. It makes you do things you didn't want

to do, say things you shouldn't say . . . and then you finally get

the glorious moment.

“You try to plod on and get through

it, and you have to find yourself and find yourself listening to

everybody else who means something to you. And then you find you are

starting to run your on show a little bit better, starting to feel

better and things seem all new.”

These days Allman lives in in Richmond

Hill, a suburb of Savannah near a city he loves. “We have 300 year

old oak trees, just beautiful. It looks like New Orleans did 40 years

ago.” He tends his tomato plants.

It has been a long haul for Allman to

this kind of comfort with himself.

The Allman brothers grew up in Daytona

beach, Florida and would sneak “across the tracks” to buy obscure

blues records by the likes of Little Milton, Elmore James and Howlin'

Wolf. Both brothers played guitar but Duane became obsessed and Gregg

moved onto piano then organ. With guitarist Betts, the double rhythm

team of drummer Butch Trucks and percussion player Jaimoe, and

bassist Berry Oakley the ABB fused blues with Southern rock'n'roll

and jazz improvisation.

They hit a peak in '71 when they

recorded at the Fillmore East, but after the death of Duane – when

they brought in keyboard player Chuck Leavell – they were never

quite the same. Still good, but different.

As tragedy piled upon drug addiction,

and musical differences came into play the Allman Brothers band

regularly broke up and reformed, sometimes with new members. Right

now, with hot guitarists Doyle Bramhall III (who is on Gregg's Low

Country Blues) and Derek Trucks (nephew of Butch and who also

plays in Eric Clapton's band), the current touring line-up is the

strongest in many years.

Gregg Allman has said he wasn't

interested in doing a solo album after the death of the band's

longtime producer Tom Dowd in 2002, but then he ran into T Bone

Burnett who had a Modem full of thousands of obscure old blue songs.

He liked Burnett – a Tom Dowd admirer – who then sent him 25

songs to consider for an album.

“I recognised very few, these were

like album cuts. Had you played me the main cut on the album I might

have maybe recognised it, but some like Little Milton tune, that one

. . . damn, the [album] is so new so me I don't even know 'em all. I

know 'em when I hear 'em though.”

“I recognised very few, these were

like album cuts. Had you played me the main cut on the album I might

have maybe recognised it, but some like Little Milton tune, that one

. . . damn, the [album] is so new so me I don't even know 'em all. I

know 'em when I hear 'em though.”

The idea was the album would be done

quick and live in Los Angeles.

“After

I got there he said, 'Wait a minute, if there's anything you got in

the bag you've written then give me one'. I had about two or three

and got one Just Another

Rider, me and Warren

Haynes wrote that and had just finished it up right before I met T

Bone.”

With

lines like “one step at a time” and “still on the run, just

another rider on that train to nowhere”, Just

One Rider suggests some

autobiographical soul-searching.

“Yeah,

somewhat. But it could be about other people, that's pretty

much what song writing's all about. There are as many ways to write

songs as there are songs.

“It's like your head is divided into

two and in the stuff floating on the right side we got different

musical licks and riffs, and on the left we got situations and

places, and the little things that come to you in a different way or

happened to your friends or are on the news.

“And all of a sudden one day you'll

be walking along and 'Zap!', two of them fuse together and the music

just fits with the words. And there are hundreds of other ways.

“Where do songs come from? Where the

hell do thoughts come from? When you find that out I'll let you know.

“[Songwriting]

today is just as difficult, rewarding, cantankerous, hair-pulling,

hair-splitting and as glorious and wonderful as the first time. I

love it. And you can't really tell when, then it gels.”

Allman says aside

from reconnecting with Dr John – the first time both had been in

each other's company clean and sober – the shape of the album was

also determined by the sound of Dennis Crouch's acoustic bass.

“I didn't realise how much that would

change things, you have one instrument as different as changing the

bass from electric to acoustic . . . and you feel it more than you

hear it. It's like the grain in the wood, a grain in the sound and if

you follow that grain it enhances the warmness.

“It's coming out on vinyl too so that

will be real warm.

“It was so good singing with it, it's like you had something wrong with your throat and it healed up and you thought you'd never sing again – and you hadn't for 14 years – and you thought, 'What the hell, I'll try'. Little do you know the voice has enhanced itself and with those instruments it's like being a kid coming out with a brand new toy and you just can't get enough.”

Allman clearly enjoyed the process of recording again – “T Bone set this one microphone in the middle of the room and it had 'RCA' over the top, one of those ancient Groucho Marx-type of microphones and got the sound with that” – and they did 15 songs in 11 days, 12 of which are on the album.

“Like I said to Mac [Rebennack, aka Dr John] on the way out of the studio 'I can't wait to get down here to do this again'. It was such a gas. That was like going to Disneyworld, he was a load of fun.”

The album includes a reworking of BB

King's obscure Please Accept My Love in the manner of Fats Domino, a

deep and moving take on the traditional I Believe I'll Go Back Home

and songs by Sleepy John Estes and Skip James which are dark and full

of menace.

The album includes a reworking of BB

King's obscure Please Accept My Love in the manner of Fats Domino, a

deep and moving take on the traditional I Believe I'll Go Back Home

and songs by Sleepy John Estes and Skip James which are dark and full

of menace.

“Oh yeah, Skip James' Devil Got My Woman, that's a scary one. The Devil, women, whisky and money. The four cornerstones,” he laughs.

Still, it did take 14 years since the

last solo album under his name. So what took him so long?

“I got married”, laughs Gregg Allman loudly, a man who has been married “at least six times” . . . and has been far too familiar with those four cornerstones.

Want to read more about the blues? Then go here for more than you fill.

.

Gregg Allman died in May 2017 of liver cancer. He was 69.

post a comment