Graham Reid | | 8 min read

On a per head of population basis,

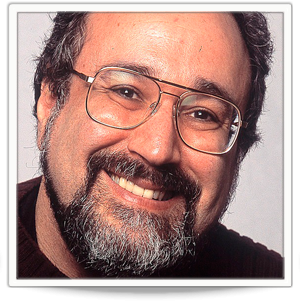

Bruce Iglauer – the founder of Alligator Records – has been the

man who has let you hear the real minority stuff.

As he said when we spoke in 1988,

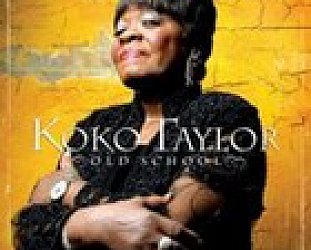

“Getting our artists on to radio is tough. Radio plays young, white

male artists and to get somebody like Koko Taylor - a middle aged

black woman and not particularly glamorous -- on to a station

catering for 20-year old white yuppie males is real hard."

In the global village, Iglauer, head of

the Chicago-based label, is like the guy in the far hut who sells you

music made by a couple of friends.

And he started his record company for

the best of all possible reasons. The music he liked wasn’t being

recorded.

"I started my label in 1971

because the company I was working for, Delmark, wouldn't record Hound

Dog Taylor and the Houserockers, my favourite band. I thought it

would be like a hobby. I knew it was a business when my phone bill

became bigger than my monthly cheque at Delmark."

By '88 Iglauer was heading a label

which had a catalogue of a hundred or so titles and included some of

the classic blues albums of the past 20 years. But it was no less a

struggle today when you consider the small sales, on some albums.

“Back in 1970, Delmark would sell

about two or three thousand copies of an album in the first year, the

Hound Dog Taylor sold 9000 in the first three months, mainly because

I was working radio and press in a way blues hadn't been marketed to

a young white audience before.

"Today an album-like Lil' Ed and

the Blues lmperials would sell about 15 to 17,000 on tape, album and

CD in total. And in order to do that we'd probably give away 3500

promotional copies plus print posters and do press kits.

“The profitability on an individual

record isn’t that great, but certain records like Showdown by

Albert Collins, Robert Cray and Johnny Copeland or Albert Collins’

Icepicker have made us a lot of money.

“They were made with a limited budget

and sold better than expected. Most Alligator records make a small

profit and the big back-catalogue supports the cash flow."

Iglauer started Alligator in 1971 with

$2500 and says the company ran for 10 years before he had to go to

the bank for a loan.

He is unashamedly a businessman –

“I'm a little jaded because I listen with a business ear and think

how can I market them?"-- but still a fan who listens to the

blues for leisure and goes to clubs and concerts regularly.

“I was part of the Great Folk Scare

of the Sixties," he laughs, and was a very amateur jug band

musician who first heard the blues at folk festivals in '66.

"By 1970 I was in Chicago and the

following year I had my own label. It was like heroin, after the

first shot you had to have the second.

“I think of Alligator as a label like

Blue Note, the classic jazz label, where records are supposed to be

on the cutting edge when they're released but also stand up over a

long period. I'm proud of what we've done but I've made mistakes.

“I passed on Robert Cray because

there was a member of the band who, at the time, wasn't a very good

player. I wanted to replace him for the record with a studio musician

and Robert refused. That was it," he says, making clear the

difference of opinion was entirely amicable.

"Robert had gone in a direction I

wouldn't have conceived of and a more successful direction than I

would have taken him."

Iglauer also had the opportunity to

record Stevie Ray Vaughn before the guitarist made the mark he did

but it's clear he is on good terms with all his artists. He is

disappointed when someone like Son Seals leaves the small, personal

roster of Alligator artists.

The label also had a brief flirtation

with reggae but Iglauer let that slip away deliberately.

“I like reggae and that's the reason

anything gets recorded on Alligator. It also fitted with our slogan

of ‘Genuine Houserockin‘ Music' because it’s rhythmic, you can

dance to it, it’s a rootsy black music tradition and it’s also

structurally simple but emotionally complex like blues.

"But frankly my experience with

reggae artists was not a happy one. Koko Taylor and the people on

Alligator know how to say those two magic words - ‘thank you’ –

and I never met a reggae artist who knew those words.

"As the leases expire we're

getting out of reggae.”

Not that Alligator needed to broaden

the base of its recording outside blues. Iglauer pointed to a healthy

blues scene and was excited about the new generation of artists like

Little Charlie and the Nightcats from Sacramento, Tinsley Ellis out

of Atlanta and Kenny Neal, the big news from Baton Rouge, whose

albums he had recently recorded.

Although he received a mountain of

audition tapes – it was August and he is listening to the intake

from March -- it is seeing a band live, as he did with Lil' Ed and

the Blues Imperials which is often the clincher.

Lil' Ed was shortlisted for a

compilation of new blues players on the Chicago scene although

Iglauer said he hadn't heard him with his own band. He caught the

band playing in a club and was impressed by how diverse they were,

pulled them into a studio for the one track and the band blew the

studio away.

The group worked up such a fever on the

one track the engineers just let them go for it and kept the tapes

rolling: “It never occurred to me to make an album with Lil' Ed.

Certainly not to make one in three hours – and we've still got

material from that one session."

The Little Charlie album came through

the more traditional route of an audition tape on the desk, although

Iglauer knew the harp player.

He flew to Sacramento to see the band

play and was impressed by the quality of songs, the humour and

astounded by the versatility of guitarist Charlie Baty. The group

were about to sign to another label but the deal was done on a

handshake and they were on Alligator.

But mountains of tapes are a worry.

“Finding good blues songwriters is

hard and most tapes have familiar songs, familiar-arrangements by

artists trying to sound like familiar people. Ever since I recorded

Johnny Winter I’ve been getting a lot of tapes from people who

think playing a million notes a second is going to get me interested.

“They don't understand the music has

to tell a story, be intense and have humour. Musicians like Steve Vai

and Joe Satriani have technique that would kill any blues player but

technique isn't what interests me. Lack of technique bothers me –

but technique is supposed to make you feel something.

"Also, I like singing. The voice

is my favourite instrument."

Judging by the success of Alligator –

the label celebrated four decades in 2011 – Iglauer made few

mistakes when it came to picking musicians to record, but he was also

acutely aware of who the music is getting to.

Each album contains an insert business

reply card and from those Iglauer can give you an exact picture of

the person who has a few Alligator albums in his collection.

“He's male -- over 95 per cent are

male - average age is 27, usually fairly well educated, at least a

couple of years at university and although we don't ask people how

much they make we do ask what job they do.

"We have, if not a white collar

audience, certainly very light blue.

"This is reinforced at concerts

where we get a lot of weekend hippies and a few weekend greasers.

They buy a lot of records and these days a lot have CD players. In

the States over one third our business is on CD."

Iglauer's company was expanding but it

was still very much a hands on business. He said it wasn't uncommon

for him to go home with a couple of thousand envelopes and stuff them

with the label's monthly mail-out to 5500 record stores while he

listened to audition tapes into the night.

The company, which employs only 17

people at the time, also worked closely with the artists and Iglauer

has been a producer and manager for many on the label.

When it comes to a tour he'll often

accompany an artist. Office staff work out every detail of an

artist’s itinerary down to “what hotel, what time to check out

and what highway to take" because the musicians don‘t have a

road manager.

It has brought the artists and Iglauer

very close which makes the loss of someone like Roy Buchanan, who

hanged himself a fortnight before our conversation, especially hard

to take.

“Roy was a very complex and troubled

man from the day I met him about six years ago," he said. "He

came from a deeply religious and very poor family - they were

sharecroppers. Roy believed in heaven and hell - and in sin. I think

he perceived himself to be a sinner and somebody who had turned away

from God and, to a certain extent, was therefore doomed.

“Roy was a very complex and troubled

man from the day I met him about six years ago," he said. "He

came from a deeply religious and very poor family - they were

sharecroppers. Roy believed in heaven and hell - and in sin. I think

he perceived himself to be a sinner and somebody who had turned away

from God and, to a certain extent, was therefore doomed.

"He never drank mildly, always to

excess and because his emotions were so locked inside him alcohol

would release these and he could do or say anything. He tried to kill

himself a year and a half ago.

“I hope his death had nothing to do

with what he was doing artistically. He was responsible for a great

number of people -- his wife, children and grandchildren – all of

whom he was raising and so his money was going away as fast as he

earned it And his life was in emotional disarray.

“I'm very sad but I wasn't surprised.

We didn't always communicate well but he was a house-guest of mine

and an extremely gracious man.

"But there was a part of him you

couldn't touch.

"When we were doing the first

album the rhythm guitarist, Chris Johnson, said to him, 'How come you

look so calm and play with all that fire?'

“Roy just looked at him and smiled

that angelic little smile and said, 'Because I'm screaming inside'.

“I think the screaming got out.”

Want to read about another blues label out of Chicago? Then go here.

post a comment