Graham Reid | | 4 min read

John Mayall (with Mick Taylor): Snowy Wood

When veteran British bluesman John Mayall played the Civic in Auckland in 2010, the concert was both disappointing and crowd-pleasing. Disappointing because, although professionally executed, it failed to really take flight. Crowd-pleasing because he played his hits.

The joke, of course, is Mayall has never had hits and at 77 it seems increasingly unlikely he ever will. But he did enjoy a particular golden period in the mid Sixties with a brace of acclaimed albums, and it was to that era he frequently defaulted to the delight of an audience largely made up of those who remember the material from that first time round.

Mayall was one of the key figures in what became known as the British Blues Boom in the Sixties but was about a decade older than the young Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Mick Fleetwood and many others who were drawing on Delta blues from Mississippi and the tough urban sounds of Chicago blues for inspiration.

Mayall, by being older and having had a deep immersion in this music before he finally turned professional in '62, was something of a mentor to young musicians, although his first album John Mayall Plays John Mayall, recorded live in late '64, hardly rattled the rafters.

But the following three album – when he formed what would become known as the Bluesbreakers band – showed him a fine spotter of talent and a major influence on the direction of a peculiarly British take on black American blues.

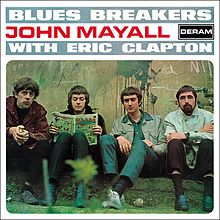

In their own way those albums – Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton in '66, A Hard Road and Crusade (both in '67) – were as influential as anything which had come out of Mississippi or Chess studios in Chicago.

In '65 young and gifted Clapton had

tired of the direction of the Yardbirds – away from rough rhythm

and blues and into the pop charts – and gravitated towards Mayall's

band. He joined, quit and then rejoined for sessions in April '66

using Marshall amps and a secondhand Les Paul guitar as he searched

to replicate the tough sounds which had come out of Chicago.

In '65 young and gifted Clapton had

tired of the direction of the Yardbirds – away from rough rhythm

and blues and into the pop charts – and gravitated towards Mayall's

band. He joined, quit and then rejoined for sessions in April '66

using Marshall amps and a secondhand Les Paul guitar as he searched

to replicate the tough sounds which had come out of Chicago.

The sessions were fast, raw and loud – and Clapton's guitar was prominent on material mostly drawn from their live set which included Robert Johnson's Ramblin' On My Mind, Mose Allison's Parchman Farm, Freddie King's Hideaway and the Willie Dixon-Otis Rush song All Your Love. In the middle of their version of Ray Charles' What Did I Say Clapton drops in a musical quote from the Beatles' Daytripper released six months previous.

The album – known as “the Beano album” because Clapton is pictured on the cover reading that kids' comic -- sang and stung in ways which people had never heard before in British blues. (For more on this album go here.)

Although Clapton – restless and insecure and still only 20 – quit again by the time it was released, it remains a highpoint in Mayall's career. And at the Civic played a number of songs from it.

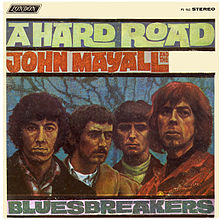

But with Clapton's departure he was forced to build a new band around the rhythm section of bassist John McVie (later the Mac in Fleetwood Mac) and drummer Hughie Flint.

He chose guitarist Peter Green whose

star was ascending and who had drawn accolades from black Americans

and British blues players alike.

He chose guitarist Peter Green whose

star was ascending and who had drawn accolades from black Americans

and British blues players alike.

Although the album A Hard Road – in a cover painted by Mayall who had been an artist and designer before turning pro – contained fewer covers (among them a version of Elmore James' classic Dust my Broom as Dust My Blues) the highlights were when Green stepped up, notably on the improvised The Supernatural which owes a debt to the of Black Magic Woman.

Green's tone, very different to that of Clapton, established his name immediately – and had outsiders congratulating Mayall on picking talent yet again.

But Green was also restless and quit to form his own band which morphed into Fleetwood Mac when McVie followed to join drummer Mick Fleetwood in the line-up.

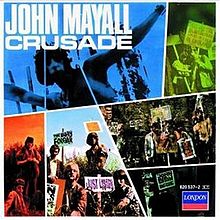

Again Mayall looked for a guitarist and for the Crusade album later that year unveiled a line-up with 17-year old Mick Taylor.

Crusade is a stronger album than A Hard

Road and Mayall contributed one of his most affecting songs in The

Death of J.B Lenoir. But again most attention was on that hot young

guitarist who was burning on material like Oh Pretty Woman and Snowy

Wood.

Crusade is a stronger album than A Hard

Road and Mayall contributed one of his most affecting songs in The

Death of J.B Lenoir. But again most attention was on that hot young

guitarist who was burning on material like Oh Pretty Woman and Snowy

Wood.

Taylor was a keeper and, perhaps by being so young, lasted the distance with Mayall into important albums like bare Wires and Blues from Laurel Canyon (both '68). Then he was seduced away to the Rolling Stones.

These three albums – the Clapton, the Green and the Taylor album in glorious mono and now available on vinyl also – were cornerstones of what was possible in a uniquely British take on the blues, so it is hardly surprising Mayall would draw on them in concert even today.

So what became of these preternaturally gifted guitarists?

Green fell victim to an LSD binge in '70, quit Fleetwood Mac (he gifted them their classic Albatross however), spent time in mental institutions and slowly made a return to playing in the Eighties.

Mick Taylor never really fitted in with the Stones – he quit in '74 – although made great contributions to albums such as Sticky Fingers and It's Only Rock'n'Roll (he says unacknowledged and unrewarded financially). But he never reached critical acclaim for his solo work. He fell prey to heroin and two years ago was close to being broke.

And Clapton? Against the odds of alcohol and drug addiction, he survived.

Today he is Eric Clapton CBE, 65, and on the cover of his latest album, playing the blues live in New York's Lincoln Center with trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, he is wearing a suit and tie.

The album opens with a New Orleans-style romp through “you scream. I scream, we all scream for ice cream”.

Some might say that too was a disappointing, but crowd pleasing, concert.

post a comment