Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Champion Jack Dupree with Mickey "Guitar" Baker: Barrelhouse Woman

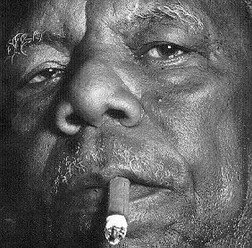

Blues pianist Champion Jack Dupree could always upset a few expectations. While his few remaining colleagues in the old blues game disavowed alcohol, Dupree told me in 1988 -- when he was approximately 80, his birth date seemed flexible – he still fancied a taste, but with a couple of crucial exceptions.

"I drink cognac and beer," he said cheerily, "but I never did drink whisky or gin. Never did like them drinks at all."

Blues followers might have been shocked by the heresy, a blues player who doesn't drink whisky or gin?

And when I asked him about the current scene in New Orleans, his home town, or Chicago, where he spent time in the depression days?

"The last time I was in the States was about l979," he growled. “'There’s nothin' there. There’s more work for me in Germany and nobody knows me in the States anyway.

"When I was there they didn't pay me no mind. I don‘t need to be in New York, there’s too much competition. Guys work for nothin' and if you name a price they’ll work for less. So why go there? There's no place for me."

For the previous 11 years, Dupree (born William Thomas Dupree) had lived in Hanover -- "right at the centre of everything" -- and before that he lived, for nearly 20 years, either in England or Scandinavia.

He had recorded dozens of albums and on his first tour of New Zealand he was bringing copies of an album he recorded for his (approximate) 75th birthday with Memphis Slim and a host of other legendary blues artists.

Dupree might have been around 80, but he was keeping good health and had behind him a lifetime which has seen him fighting as a boxer, a professional chef, prisoner of war for two years in Japan and for the last 40 years a professional blues pianist.

After his parents died in a house fire when he was about 10, Dupree had been placed in a New Orleans orphanage and he began to frequent local bars to watch the pianists, one legendary character called Drive ‘Em Down (Willie Hall) in particular.

“Life in the poor parts of New Orleans for a black boy was really tough and I learned a lot about life on the streets. I was on the streets most of the day and in the clubs listening to music every night.

“I used to watch Drive 'Em Down and I would sing with him sometimes ‘cause I was too young to play in those places He was one of the greatest barrelhouse players and when I watched him I just wanted to bang on the piano.

“Other children would play marbles but I always just wanted to play piano. So they got a piano for me in the orphanage. The Salvation Army found one and gave it to us.”

But it was to be another couple of

decades before Dupree took to playing professionally.

But it was to be another couple of

decades before Dupree took to playing professionally.

Under the tutelage of local fight trainer Kid Green, he took up professional boxing.

“All through the Thirties I was fighting and I was fairly successful – that's how I got my professional name, Champion Jack Dupree.”

Reports vary on how successful he was as a boxer, the most generous has him as a lightweight champion form '33-'34. The least generous has him slugging it out against all comers in cross-country challenges for $40 for six rounds, winner takes all.

"You didn't make any real money, just $10 for four rounds and although that wasn't much, it helped.”

During the Depression he was in Chicago and became second cook in a restaurant :"The best job to have during the poor time,” he laughed. "At least you could eat."

Until he joined the army in '40, Dupree played a number of clubs, the most notable being the Cotton Club in Indianapolis where his repertoire consisted of Drive 'Em Down's material, New Orleans classics and covers of songs like the famous Drinkin' Wine Spoo-Dee-Do-Dee, a hit for Sticks McGhee, Brownie's brother.

During his two years' captivity in Japan, he was also a cook for the officers but says thing weren’t too tough for blacks in the POW camps.

“Black people lived good because they weren’t put with the whites We cooked for ourselves and played ball.

"The Japanese were funny. They thought Americans were getting black slaves from Africa to fight for them so they didn't see they were fighting us. The reason for that was the Americans didn't allow blacks in the Navy then, so every time a ship went to Japan there weren't any blacks on lt. When the war came the Japanese thought the Americans were just using blacks."

But if he denied things weren't too tough, he was also bitter about the treatment he received on his return to the US.

"They don’t give you nothin' for that to-day. Only when you die. They give you a flag, but you can’t eat a flag."

After the war Dupree, too old to return

to the ring, took to professional blues piano playing and quickly

established a name for himself.

After the war Dupree, too old to return

to the ring, took to professional blues piano playing and quickly

established a name for himself.

He worked with Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry and began a lifelong touring habit. He toured extensively throughout America and Europe and recorded frequently, especially during the British Blues Explosion of the mid Sixties when he recorded with the likes of Paul Kosoff of the band Free and members of the then blues-based Fleetwood Mac.

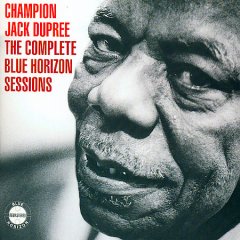

He recorded with Mickey “Guitar” Baker an Alexis Korner, was signed to the Blue Horizon label and one album, When You Get The Feeling You Was Feeling, has Dupree telling the story of his life and interspersing songs he had written.

Although New Orleans was a long way in his past, he told me with pride of being part of the Yellow Pocahontas Indians.

“That's my mothers tribe. She was any American Indian and father was from Africa and I can’t forget that.

“In New Orleans there's Creole, Cherokee, Mohawk and the Yellow Pocahontas, which is the darkest race of Indians. Each tribe has its own traditions and some of those Indians play good jazz or blues.

"Most of the musicians you get from New Orleans are the Black Indians.”

Two years after we spoke in '88, Dupree was coaxed into returning to New Orleans to play at the Jazz and Heritage Festival, a city he had last seen in '54. He was enthusiuasticaly received and stayed on to record an album, Back Home in New Orleans, and in '91 he returned again for the festival.

But these would be among his last appearances.

Champion Jack Dupree died in Hanover, Germany in January 1992.

No one could say exactly how old he was.

Like the sound of the blues? Then take the time to explore here.

Clive - Jan 31, 2012

Back in the late 60's I bought a record by Jack called ''From New Orleans to chicago".It had a cool cover showing his face in black and then a road map over it in red going from Orleans to Chicago.As an 18 year old kid I had never heard of Jack,however at the bottom of the cover it said featuring among others Eric Clapton,John Mayal and Keef Hartley amongst others,so that was the reason Ibought it! I enjoyed the record so will look out for this one as being Mike Vernons Blue Horizon lable will no doubt include the stuff of my old record which is long gone

Savepost a comment