Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Dave Alvin and Phil Alvin: Southern Flood Blues

Dave Alvin has, as they say, miles on the tyres. At 59, the acclaimed guitarist and singer can look back to the roots-rock band the Blasters he formed with his brother Phil in the late Seventies, a band that blended punk energy with Americana and blues, and shared bills with the likes of Black Flag and The Gun Club.

The Alvin brothers however had one of those volatile sibling relationships – like the Davies and Gallagher brothers – and after seven years he quit and joined X, then a series of other bands before embarking on a solo career.

Singer/brother Phil went back to university and became a professor of mathematical semantics, although still managed to get out a couple of solo albums.

Recently however the brothers have come back together – first for a Blasters reunion then Phil appearing on Dave's witty song What's Up With Your Brother? (“all anyone asks is . . . ”) for his Eleven Eleven album.

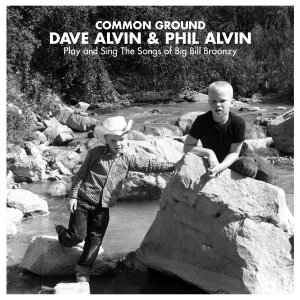

And then last year they completed a

whole album together, Common Ground: Dave Alvin and Phil Alvin Play

And Sing The Songs of Big Bill Broonzy. The first part of that title

is telling – as Dave says, “We don't argue about Big Bill

Broonzy” – and the album was highly praised for how they

reconstituted and interpreted songs by the old bluesman whose music

they bonded over as teens.

And then last year they completed a

whole album together, Common Ground: Dave Alvin and Phil Alvin Play

And Sing The Songs of Big Bill Broonzy. The first part of that title

is telling – as Dave says, “We don't argue about Big Bill

Broonzy” – and the album was highly praised for how they

reconstituted and interpreted songs by the old bluesman whose music

they bonded over as teens.

It debuted at number one on the Billboard blues charts and was also nominated for a Grammy but lost out to the late Johnny Winter.

Dave took to Facebook with this comment: “Ya win some, ya lose some. The highlight of Grammy Day for me was getting to meet and hang with the invincible Blues-Funk highway king (and fellow nominee for Best Blues Album), Mr Bobby Rush. I thought for sure he'd win the Best Blues Album award but they gave it to the late, great Mr Johnny WInter instead. I have to admit I was afraid that if my brother and I did win the blues award that Mr Bobby Rush would hate our damn guts. So if there is any consolation for losing at the Grammys today, it is that I can happily and most assuredly say that Mr Bobby Rush does not hate our damn guts.”

The Alvins and their band the Guilty Ones come to Wellington's Bodega on April 1 and Auckland's Tuning Fork on April 2 so we snatched some quick time with Dave at his home in California.

Commiserations on the Grammy, but I loved that comment about Bobby Rush. I assume you must have gone into that with high hopes and expectations.

It was disappointing. I won a Grammy 13 years ago so I got one. So what I wanted was one for my brother, that was why I was disappointed.

We don't necessarily make music that easily fits into genres and they changed the Grammys to where they added this stuff like 'best Americana song' and all that . . . and I don't even fit into Americana.

I tend not to make records that fit categories even though I basically consider myself a blues guy. But some people I guess don't. So to do an album that was obviously a blues record . . .

I don't know what my brother and I will do next – so this might have been his one shot at a Grammy. So I was disappointed about that.

But I kinda figured going in that it was either Bobby Rush or Johnny Winter. Bobby lost to Charlie Musselwhite the year before when Charlie had the album with Ben Harper so I figured he wouldn't win two years in a row so I thought they might give it to Bobby Rush because he lost. But then Johnny Winter was tough competition in that category.

It was all more of a lark to be but it would have been great if Phil had won and he could give a little speech and we could put him in a suit.

But at least Bobby Rush doesn't hate me. You gotta love that.

The Common Ground album . . have you been surprised by just how well it has been received? It began as a very modest project I believe.

There are certain people who don't like

my solo stuff for whatever reason – ie. my voice – but there's

nothing I can do about that, and knew there were Blasters fans who

still hold a grudge after all these years for leaving the band and

whatever else, but I knew that they would like it and this would mean

a lot to them. I didn't know what it might mean to fans of my solo

work, but the main idea was just to make a record for me and my

brother.

There are certain people who don't like

my solo stuff for whatever reason – ie. my voice – but there's

nothing I can do about that, and knew there were Blasters fans who

still hold a grudge after all these years for leaving the band and

whatever else, but I knew that they would like it and this would mean

a lot to them. I didn't know what it might mean to fans of my solo

work, but the main idea was just to make a record for me and my

brother.

I knew it would resonate with a lot of people because we're at that age where people are passing away and you're at that point in your life where you reassess bad decisions you made throughout your life.

You are on tour at the moment and I understand you are fitting Blasters songs into the set too.

Fittin' everything in. We do about two thirds of the Big Bill album, the rest goes between songs from my solo career and three or four Blasters songs and we throw in a couple of odd covers.

I hope when you come down here you are going to do Johnny Ace is Dead.

Consider it done, we do it at every gig.

I have to ask, how come two white boys from suburban California found the blues as you and Phil did? Were you hearing this on the radio? Like Border radio?

I dunno, would you ask the same thing to Ry Cooder from Santa Monica or Bonnie Raitt from Glendale, California?

I think I have actually.

(Laughs) Right, okay. Well, California was a state full of people from diasporas, during the Dust Bowl you had people who came out Oklahoma, Missouri and West Texas, then you had the African-American migration as people tried to escape from Jim Crow laws in the South . . . so they all brought their music with them.

So it was easy to find although we had friends our age who had no idea what we were doing at night. We were little kids sneaking into bars to see T Bone Walker and Big Joe Turner and Lighting Hopkins. We figured out fairly young that not only were these guys a love but they were living and playing nearby and you could actually see them. And the community they played for was still somewhat in existence. It was community music and they were folk musics, they weren't folk music with acoustic guitars and striped shorts, so at that time it was easy to access.

You certainly heard some of it on African-American radio or Border radio stations as you say, you'd hear Johnny Ace, Howling Wolf, Junior Park, Freddy King and people like that.

It was all there, from that to Merle Haggard. That's what we grew up hearing.

Do you recall the first time you heard

Big Bill Broonzy?

Do you recall the first time you heard

Big Bill Broonzy?

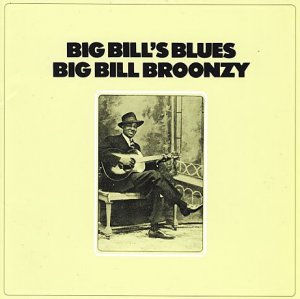

Oh yeah. My brother was 12 and he brought home an album called Bill's Blues. He ha d no idea who Big Bill was but he saw the word 'blues'. It was all recordings from the late Thirties, it was one of the few reissue albums in that era. He put it on and that was that, wrap it, we're done. (laughs)

You fell for it instantly and thought, 'Wow, this guy is speaking to me'?

Yeah, because he had that kind of voice. He had a 30 year career too. Howling Wolf's voice was all power and mystery, Muddy Waters was all power and glory and Big Bill had a big voice and it was certainly powerful. But the tonality of his voice was friendly and welcoming, even when he was singing violent songs. And he had several.

His voice was that of a friend and that's why in the blues community he was just referred to as Big Bill, he was like Uncle Bill. He was your pal.

His personality jumps off the grooves and he instantly becomes somebody you've known all your life. He had a strong personality.

Given he recorded over 30 songs was it difficult to chose songs for the album, or did you and Phil just think, 'Well we have to do Key to the Highway'?

Some did. Some were songs that were on

that first album which my brother started singing immediately. There

was no question we would be doing Trucking Little Woman and I Feel

So Good and Big Bill's Blues.

Some did. Some were songs that were on

that first album which my brother started singing immediately. There

was no question we would be doing Trucking Little Woman and I Feel

So Good and Big Bill's Blues.

Key to the Highway we went back and forth on because it has been done many times so how do you do it different. I came up with an idea though because my brother took harmonica lessons from Sonny Terry when he was about 13 years old so I thought we could do it like Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee would have done it. Once we decided on that, it was real easy.

My brother's got a voice that is tailor-made for Big Bill songs and mine is made for something else. For the songs I'm doing the lead on I wanted to do songs which were more story and lyric-driven than vocal-driven. Sometimes you can have a great song but they lyrics are meaningless even though the vocal is great. So I was trying to find story-telling songs because that's been my framework.

Southern Flood Blues stands out for all those reasons, there's a story but it is also very dark.

Oh yeah, and I changed that drastically. The Big Bill original is kind of a mid-tempo thing. I used Big Bill guitar figures . . . but it's now more approaching Magic Sam.

post a comment