Graham Reid | | 11 min read

John Psathas is one of this country's most prolific and diverse composers, and the most internationally acclaimed.

The New Zealand-Greek composer came to global attention when his music was heard during the Opening Ceremony of the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens.

Since then his work has been commissioned by international and local artists, he is a NZ Arts Foundation Laureate and his music has been played in more than 50 countries on all seven continents, even Antarctica.

Psathas was a faculty member at the New Zealand School of Music, Victoria University Wellington for 25 years, before leaving in 2019 to devote his time to composing and a return to performing.

He has appeared at Elsewhere many times (in interviews and reviews), has collaborated on a Billboard classical chart-topping album with System of a Down front man Serj Tankian, has written feature-film scores, done projects with jazz musicians Michael Brecker and Joshua Redman and collaborated on an e-book project with Salman Rushdie.

Covid-19 lockdown didn't slow him, last year saw the release of collaborative albums It’s Already Tomorrow, and Last Days of March. He mentors a wide range of composers and performers, and hosts composer retreats at his haven at Waitarere Beach. He was recently named one of 12 recipients of the 2021 Absolutely Positively Wellingtonian Awards.

Covid-19 lockdown didn't slow him, last year saw the release of collaborative albums It’s Already Tomorrow, and Last Days of March. He mentors a wide range of composers and performers, and hosts composer retreats at his haven at Waitarere Beach. He was recently named one of 12 recipients of the 2021 Absolutely Positively Wellingtonian Awards.

He speak with Hannah Darroch about his career and the politics of music.

You are known for your musical works of epic proportions - what would you say has been (or is about to be) your most ambitious project to date, and why?

The thing is, if you get to work on the Olympic ceremonies, it totally shifts the bar. After 2004, my idea of what a mega-project was, was probably different from most other composers. And that's why I continue to blindly stumble into massive projects. They don't seem so big by comparison. And that's why they're usually my idea (something I have to remind myself of at key moments in the inevitable stress tsunami). No Man's Land - with its 150 musicians from 25 nations, filmed and recorded in multiple countries - is a close 2nd, and CubaSonic with its 300 musicians lined up along Cuba Street in Wellington with a 60-speaker synchronised PA system, is in 3rd place.

But even the next level down - World of Wearable Arts (WOW), the film scores, the ebook-score collaboration with Salman Rushdie, the crossover orchestral projects with Little Bushman, with Serj Tankian, and with Greek folk musicians - they are each, individually, massive undertakings. So when I'm working on what you'd think was a big project, like a double percussion concerto, it feels way more manageable.

The scope of your work is immense - can you describe the process of collaborating with such a wide range of other events/festivals/groups (e.g. the World of Wearable Art, CubaDupa, Shapeshifter)?

In the early part of my career, I collaborated very little. It was a confidence thing. But over time and through some very fortunate early collaborations, I had such great experiences that I realised this was a way to be more in the world, and to experience different approaches, and musical styles. I've also ended up making most of my friends through collaborative work. I've found the process of working with others is unique to each project, due to the unique chemistry between the artists and organisations that have assembled for this one-time collaboration.

The best experiences though, are when I can meet and hang out with people I'm creating music with. It is, after all, about human connection, which starts in the creators of the work, flows through to the performers and presenters, and arrives at the sharing of the work with audiences.

From that angle, the most incredible collaborative experience was No Man's Land, where I spent time in person with the most amazing musicians from Morocco, Greece, Turkey, Poland, Senegal, India, Pakistan, France, Iran, Bulgaria, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, Italy, Japan, and more. Just being in their presence, hearing them play, and talk about music and life and their culture, was one of the greatest gifts.

And then at the other extreme, is a recent project where I worked very closely, over an extended time, with New Zealand singer/songwriter Christine White. This was an incredible, very rare opportunity to share in her deeply personal world, and her unflinchingly honest artistic vision.

What have been the landmark or pivotal works that really launched your career or led to particular future commissions or collaborations?

In 1992 Evelyn Glennie played a piece of mine at the NZ Festival at the Michael Fowler Centre in Wellington. This piece - Matre's Dance - launched me internationally. Evelyn, who was herself at the start of a journey that would make her the No.1 percussion superstar of the world, played it everywhere she went. I mean it received over a thousand performances by her. And a good percentage of Evelyn's audiences were aspiring percussionists, who then wanted to learn that piece.....

That's happened once more since then, with a piece called One Study One Summary, which Portuguese virtuoso Pedro Carneiro commissioned. When he was here, we made a film of him playing it, and put that online. That piece has now become a staple of percussion repertoire the world over. There are countless videos of it on YouTube, and it's also used as repertoire in international percussion competitions.

That's happened once more since then, with a piece called One Study One Summary, which Portuguese virtuoso Pedro Carneiro commissioned. When he was here, we made a film of him playing it, and put that online. That piece has now become a staple of percussion repertoire the world over. There are countless videos of it on YouTube, and it's also used as repertoire in international percussion competitions.

And this is just starting to happen again with a third piece called Kyoto, also for percussion.

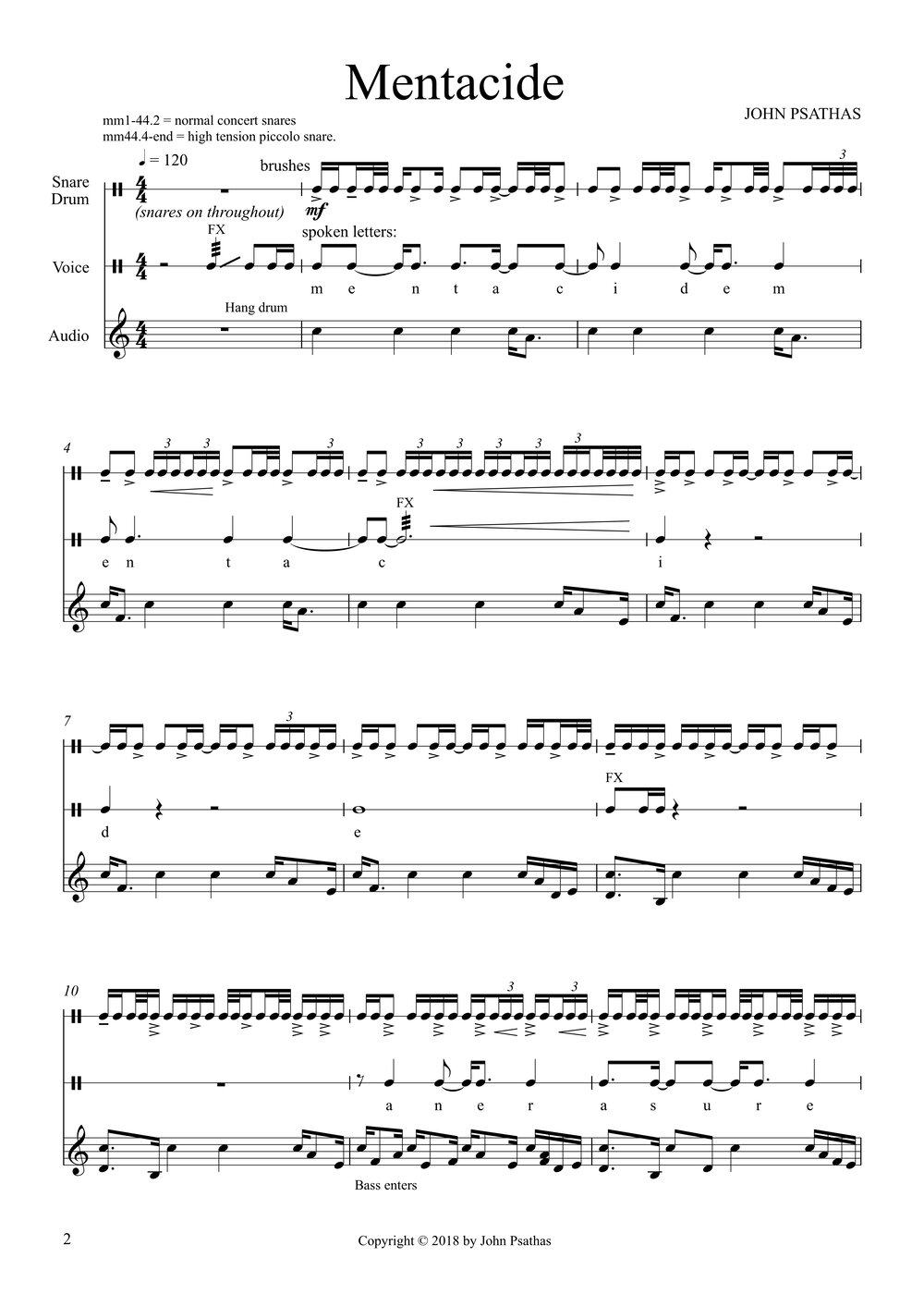

So, despite all those big projects I've been a part of and am known for, it's the percussion music that's led to most of the commissions, performances, concertos, recordings, and new projects. I think I'm best known 'out there' more as a composer for percussion than anything else.

It can be surprising how some things eventuate; a fanfare I wrote was performed as the doors of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa opened for the very first time in 1998. This fanfare, recorded by Radio NZ, was later heard by the team selecting the composers for the Athens Olympics, and convinced them to bring me on board for the ceremonies.

How would you describe the future of music in this country?

This is very dependent on the kind of support the arts receive. From certain perspectives we are incredibly, I mean incredibly, lucky in New Zealand. We have so many organisations and presenters here that support our music: Creative New Zealand, NZ On Air, SOUNZ, APRA, Radio New Zealand and dozens of other radio stations and networks, the venues, the orchestras, the promoters, the labels, the music societies, the festivals, and the many I haven't listed.

These organisations are run by people that really care about New Zealand music specifically. All a New Zealand musician needs to do is talk with similarly-placed artists in other countries to get an idea of how fortunate we are here.

I hope that New Zealand music moves more into the space of societal and political expression. We need as many expressive voices as possible to be confronting or commenting on the major (now species-threatening) issues and challenges that we're faced with. I feel like I've just woken up to this recently myself. The challenge is that music is so good at giving people a good time.

In fact, music is one of the great balms for taking the pain away and allowing us to forget our problems for a while. But it also has immense power to confront, and to challenge the status quo. Music is such a beautiful thing when it's comfortable. And so powerful when it's not.

My big worry about the future of music in this country is whether or not travel will ever return to what it was. This is such a crucial component of our arts future, given our physical distance from the rest of the world. Like many other New Zealand artists, my own travel was one of the most significant factors in developing my confidence to think of myself as comparable to similar artists abroad. And that's travel both ways; it’s also about the artists that come to us from all over the planet and what they bring.

I feel for our festivals right now, trying to plan years ahead, with this level of uncertainty.

You went freelance not long before the pandemic (but have remarkably had your works performed in 34 countries since leaving NZSM) - has COVID had an impact on your work, and on composition more generally?

It's been amazing how well things have continued for me during Covid. The last 18 months have definitely impacted on my work and composition, mostly in terms of what I value. It no longer feels like it's enough to create a new piece of pure music. I now feel an internal pressure to add layers to new work, so the meaning and messaging become multi-dimensional, and at the same time more direct.

It's been amazing how well things have continued for me during Covid. The last 18 months have definitely impacted on my work and composition, mostly in terms of what I value. It no longer feels like it's enough to create a new piece of pure music. I now feel an internal pressure to add layers to new work, so the meaning and messaging become multi-dimensional, and at the same time more direct.

Sometimes a piece of music shapes its own purpose (like a character in a novel that does what it wants, regardless of the author's intentions), in those cases I'm more like a midwife. Other times I'm able to grab the reins and have most of the overall shaping power. The last few years have put me far more in the latter space than the former....

You’re the recent recipient of an Absolutely Positively Wellingtonian Award for your contribution to the cultural fabric of the local community - how would you describe the arts scene in Wellington, and how has it shaped you as a composer?

Wellington is a (can I say 'the'?) cultural hub of New Zealand. I've been here since 1984 and it's had everything I've needed. This international career I enjoy has been created and sustained from a Wellington home base.

Wellington is a (can I say 'the'?) cultural hub of New Zealand. I've been here since 1984 and it's had everything I've needed. This international career I enjoy has been created and sustained from a Wellington home base.

Two orchestras, choirs, Chamber Music New Zealand and Creative New Zealand headquarters, the New Zealand School of Music, Massey's Commercial Music degree, Whitirea, Ta Auaha, a supportive City Council, the New Zealand Festival, CubaDupa, Newtown Festival, the Jazz Festival, venues like San Fran, Meow, Valhalla, Moon, and more, a vibrant multi-ethnic, multi-genre melting pot of musicians, the Miramar film industry (including Park Road Post, one of my favourite places to work out of anywhere), community-based events, and on and on.

There is so much here. It's also been a great place to raise our children, and for me there's the added bonus of the Greek Community.

For the size of the city Wellington culturally packs a mighty punch. We're sorely feeling the current absence of the Town Hall and the St James, but they'll be back soon. We could also do with more big name international stadium acts coming to Wellington. And I do hope that the plan to bring the New Zealand School of Music into the heart of Wellington's Civic Square happens soon also. That will have a perceptible impact on the vibrancy of the city's centre.

Looking back over the past three years since leaving the safety net of a university professorship, how have your goals and your mindset as an artist shifted?

They've really shifted. Whether you want to acknowledge it or not, having a secured salary as an artist is very likely to impact on how provocative, challenging, or risky you're prepared to be. With that kind of secure job (which I enjoyed and benefited from for 25 years) you're always aware that there is something to lose.

Now that I'm out in the world freelancing I feel less bound creatively. I'm also freer politically and have been gravitating increasingly toward a creative energy that produces new works with extra-musical meaning. Music that is inspired by social, political, historic, and climate-driven thoughts and feelings. I've been spending a lot more time getting to know what's happening in the world and exploring different opinions and perspectives on the key issues of our age, like identity politics, the last 100 years of history and what they've led us to, the future we're handing on to the next generations, the disenfranchising of youth, and the global disestablishment of social spaces.

Leaving university was one of three steps in creating this much bigger space in my mind to reflect and consider; the other two steps have been finding a place by the sea at Waitarere Beach where I spend a lot of time, and.....leaving Facebook, which has led to a profound shift in my attention and my ability to focus on less mundane things.

That's the mental shift. In terms of music, both the quantity and quality have taken huge leaps. I've written an incredible amount of music in the last three years, and it's orders of magnitude better than most of what I've done in the past. My creative muscle is the strongest it's ever been, with weeks of 12-14 hour days flying by in the creative process.

That's the mental shift. In terms of music, both the quantity and quality have taken huge leaps. I've written an incredible amount of music in the last three years, and it's orders of magnitude better than most of what I've done in the past. My creative muscle is the strongest it's ever been, with weeks of 12-14 hour days flying by in the creative process.

There's also more meaning in the work, and I can see with audiences that it's not just generating a visceral, sensual experience of sound, but it's also triggering concepts and thought processes about ideas beyond music. This is definitely a space I'm enjoying being in as a composer.

How do you balance the requirements of collaborative projects with also creating work that is distinctly “yours”?

Collaborative projects make up about a third of my overall output. In some ways they’re easier, because the creative vision is shared, and I don't have to spend hours looking at a page of blank manuscript that I'm supposed to cover with great ideas. But even in collaborative projects I can really only be me. I've never learned how to be anyone else, or speak in a musical voice that isn't, at core, my own.

The amazing thing is that whether it's a joint-project or totally my own work, every project inevitably reveals more of me to myself. I think this is why people do art. It's a self-revealing experience.

When I write my own works - say, writing a work commissioned by a European orchestra - I am completely free to do what I want. Literally starting with no musical constraints, just the duration of the piece and the instruments I can use. I've never had writer's block, but at the same time I'm totally ruthless at denying material the right to exist in a work. The amount of material I reject is greater than the material that eventually ends up in a piece. All of it has to earn its place.

Collaborative projects tend to be more fun and less stressful, and the sign-off on what stays and what gets rejected is usually a group decision of some kind. But the works that are totally mine tend to be more of an immersive, ecstatic experience from start to finish, and I spend most of the journey not being able to wait to hear what happens next.

You clearly enjoy mentoring young composers and developing new talent here in NZ, including your work with the annual NZSO Todd Young Composer Awards: what do you enjoy most about this work?

I do this because I get a lot out of it. Being around talented emerging artists is a privilege. There's a special, still-pure energy that is inspiring and infectious. I also enjoy the validation of sharing something I know or think, that a younger artist might not have come across yet, and finds useful.

An arts subject taught at university today requires detailed qualitative assessment criteria, and tightly managed timeframes. It's been interesting engaging with young composers since I left university. Mentoring privately has been more a case of getting to know the individual and their aspirations, and learning how their art relates to them as a person, and how they perceive the world and their music in it.

This gets us to a place where the conversation is as much about what their music can mean in society, as much as it might be about the rhythms and melodies. I've been enjoying it immensely. At university, I used to struggle with teaching a creative, deeply personal calling like composition to young people I didn't know very well.

.

For more on John Psathas including video interviews, a catalogue of his works and writings, and more, check out his website

.

post a comment