Graham Reid | | 11 min read

It happens occasionally. Someone writes a novel, presents a paper or makes a movie which, as history subsequently unfurls, appears prophetic.

Think of H.G. Wells' The Shape of Things to Come, written in the early 1930s, which anticipated a global war and space flight.

Or George Orwell's satirical fable Animal Farm of 1946 which, with pessimistic accuracy, skewered communism.

As the Twin Towers fell in clouds of dust, smoke and human agonies last year some were reminded of the well publicised essay by Samuel P. Huntington, professor of the science of government and director of the John M. Olin Institute for Strategic Studies at Harvard University.

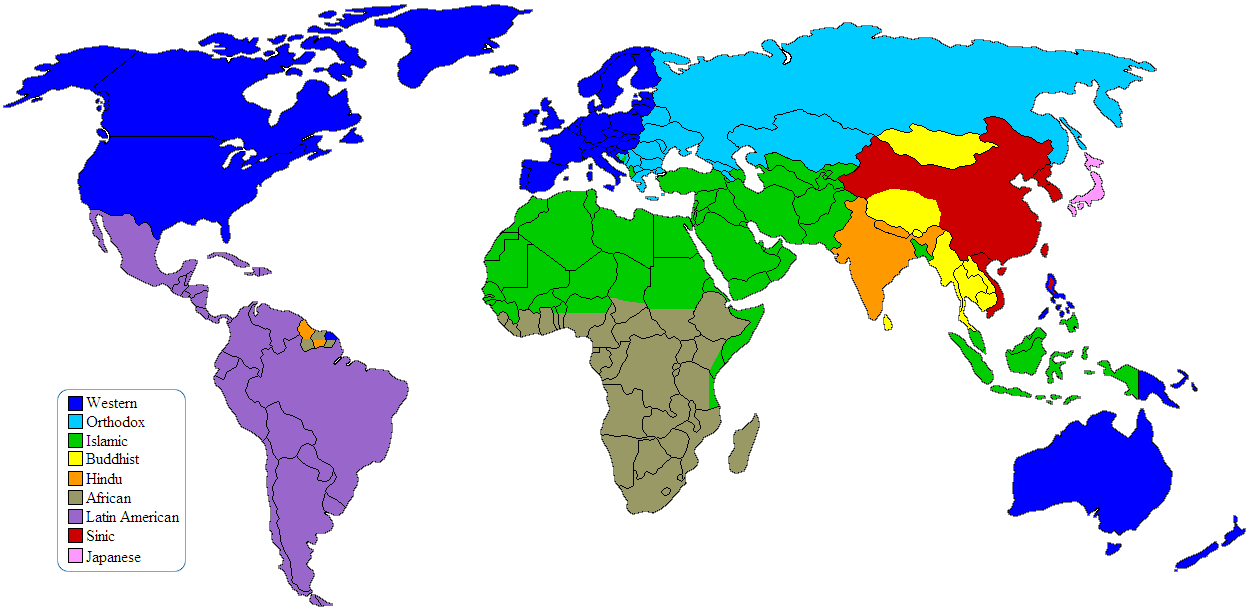

In 1993 Huntington postulated in The Clash of Civilisations that after the end of the Cold War we entered a new phase of history where the world divided itself more clearly along lines of civilisations differentiated by history, language, culture, tradition and religion.

The question, therefore, changed from that of ideologies ("Which side are you on?") to that of identification ("What are you?").

"[Identification] is a given and cannot be changed," said Huntington.

He argued these divisions between the eight civilisations he defined - which included Islamic, Western and Latin American - were more fundamental than those between ideologies.  Although he pointedly said they need not lead to conflict, where such civilisations rub against each other (for example Kashmir where Islamic and Hindu meet) there is friction.

Although he pointedly said they need not lead to conflict, where such civilisations rub against each other (for example Kashmir where Islamic and Hindu meet) there is friction.

When they collide head-on - as some say happened on September 11 - they are explosive.

Huntington's controversial views were a flashpoint for debate throughout the 90s but were discredited for their broad-brush divisions. Certainly the billion-plus Muslim world spread across more than 50 sovereign states is more nuanced and regional than Huntington concedes.

However, as the television images of September 11 were endlessly replayed and the body count climbed, the "clash of civilisations" idea was resurrected.

Had Huntington's concept been cruelly crystallised by the Islamic terrorists?

Writing six weeks after the attack, the foremost commentator on Palestinian affairs, Edward Said, in an article headed The Clash of Ignorance, re-addressed Huntington, nailing him as "someone who wants to make 'civilisations' and 'identities' into what they are not: shut-down, sealed-off entities that have been purged of the myriad currents and countercurrents that animate human history, and that over centuries have made it possible for that history not to contain wars of religion and imperial conquest but also to be one of exchange, cross-fertilisation or sharing".

As Robert D. Kaplan noted in his critique of Huntington, "The 'Clash of Civilisations' is a romantic term, conjuring up massive armies divided by race, language and religion, advancing across battlefield thousands of miles long, wielding banners of the cross and crescent. The reality is different".

Huntington's ideas may have been dismissed by many intellectuals but, says Dr Muhammad Musa of the school of journalism at Canterbury University, his concept was widely adopted within the United States and is now endemic in American geo-political thinking.

It has been used to justify growth of the military and confirmed a reactionary, conservative world view that enemies were everywhere. The media, unwittingly or otherwise, supports this construction.

The dominant Western worldview is antagonistic and where once the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe were "the other" - to adopt Noam Chomsky's term - to be kept in check and frequently demonised, the focus has now shifted to the Islamic world.

In the past year Islam became a subject producing more value judgments than reasoned analysis.

"Although the Cold War is over, the 'other' still has to be there to justify defence spending," says Musa. "Huntington is taken seriously in the [US] State Department so attention is now focused on China and Islam to see if the predictions unfold, and maybe to forestall the repercussions."

The idea of a grand coalition of Islamic states versus the West has not been validated by history.

Writing almost a decade before September 11, Huntington had darkly noted that during the Gulf War - in which one Arab country invaded another, then fought a coalition of Arab, Western and other states - Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein called on kin-country support and explicitly invoked an Islamic appeal.

King Hussein of Jordan called it a war "against all Arabs and all Muslims and not against Iraq alone" and others in the Islamic world said much the same.

But those appeals failed -as did similar ones by Osama bin Laden - and today Islamic states, even within the Middle East, are as disparate and divided as the countries in Europe, Asia and the African continent.

There is every representation of the political spectrum from Islam populists through modernist states to the Islamic jihad movements.

As Dr Ron Macintyre, a specialist in modern Middle East politics and Islamic studies at Canterbury University observes: If September 11 was supposed to have had a galvanising effect on the commonalities of the Islamic world it hasn't occurred.

"I have not seen any evidence of Islamic states working together through their organisations to beef up a militant response to the United States."

Yet the Islamic world has undeniably been changed since September 11.

Musa says negative imaging of Islam in Western media has created some solidarity among resistance groups within the Islamic world who have now further confirmed what the Western media has been saying about their extremism. "But that is in response to how they were already being perceived."

He notes President Bush's characterisation that you are "either with us or against us" in the war against terrorism allowed for no middle ground within the Islamic world.

Certainly the response to September 11 in the Islamic world was mixed. A heartfelt sympathy over the human suffering caused by the attacks was often tempered with the belief that the United States had for too long been shielded from the world's harsh realities, some of its own making.

Djamila Guerrabi, a 32-year-old doctor in Algiers, encapsulated what many were thinking when he recently said he was shocked by the terrible loss of life on September 11.

"I told myself that the cause of this was, of course, Islamic fundamentalism. But equally to blame is American arrogance, which assumes the right to make decisions for others."

Macintyre points out: "The people who perpetrated that attack have often been inflated in terms of their importance within the Islamic world. They represent the meagre few, deluded souls engaging in this so-called historic drama, a bit like the Middle Ages where you had the Crescent versus the Cross.

"Their perception is that the United States is a great Satan, but their motivation is a religious-political ideology.

"The majority of Muslims would find al Qaeda unacceptable, but other groups may feel the United States' foreign policy has provoked it. They don't share the response but they do share the sentiments."

So was September 11, as adherents to the Huntington theory suggest, about Islam versus the West, a murderous update of the old Cold War stand-off?

Edward Said: "The carefully planned and horrendous, pathologically motivated suicide attack and mass slaughter by a small group of deranged militants has been turned into proof of Huntington's thesis. Instead of seeing it for what it is - the capture of big ideas (I use the word loosely) by a tiny band of crazed fanatics for criminal purposes."

Why not, argues Said, "instead see parallels, admittedly less spectacular in their destructiveness, for Osama bin Laden and his followers in cults like the Branch Davidians or the disciples of the Rev Jim Jones at Guyana or the Japanese Aum Shinrikyo?"

Add to the skewed interpretation of the act of terror the vocabulary of apocalypse designed to inflame and you have a scenario in which labels such as "Islam" and "the West" mislead, argues Said.

The labels carry the implication that Islamic states are backward. Yet in Islam there is an important and ongoing debate over modernity.

Suroosh Irfani, a Muslim intellectual in Pakistan: "We have access to the artefacts of modernity - which means the media, the cable television, the tape recorder, the aeroplanes, the high-rise apartments, autobahns. But we lack the intellectual underpinning of what modernity is all about."

Modernist concepts of rationalism, scepticism and individualism may appear to have little place in the Islamic world which, according to Egyptian philosopher Hassan Hanafi, rejected pluralism and liberal thought at the time of the Crusades.

The profound Muslim philosopher al-Ghazali argued orthodoxy over reason and scepticism to preserve the purity of Islamic thought.

A further problem is that modernism comes wrapped with westernisation, which is often seen as a direct threat to Islamic precepts and local cultures.

Even so, within Muslim communities there is, and has long been, continuing internal dialogue about the nature of the faith in the modern world.

As David F. Forte, professor of law at Cleveland State University, noted last October, Osama bin Laden and the Taleban were a perversion of Islam and engaged in a campaign to change Islam itself. Islam is a many-voiced faith but extremists would make it monolingual, speaking with their tongue alone.

Forte says much of the extremism has been inspired by the writings of radicals such as the Egyptian Sayyid Qutb, who believed virtually all of Islam was in a state of unbelief and needed to be reconquered.

These are "Islamists", says author Salman Rushdie, those who see their faith as a political project, and his use of the term is distinct from the more politically neutral "Muslim".

And while the extreme of Sharia law - such as the recent sentencing of a young woman to death by stoning in northern Nigeria - make for alarmist headlines, there is considerable internal debate on Koranic law.

As Rushdie noted in a New York Times article, most Muslims are not profound Koranic analysts. And the laws themselves are hard to define, says Canterbury University's Macintyre.

Sharia is often loosely defined as a series of regulations of conduct based on the Koran and the way in which the prophet Muhammad conducted himself or statements attributed to him.

Parts of Nigeria are conservative and literalist in their interpretations, but equally there are modernist Muslims, says Macintyre, who constantly analyse "how to make this corpus of medieval laws relevant to the 21st century, [they] try to use science and reason".

It is a convenient myth that religious law is immutable and many are calling for a new ijtihad, or development of law from its sources to meet modern conditions.

Musa says the agenda of much of the media in this country is determined by the priorities of the international media on which we rely.

But where previously he observed a "genuine ignorance among journalists in this country because of geographical distance from Muslim countries", there is now a curiosity and concern to understand more fully, and interpret more clearly, the diversity of thought among Islamic peoples.

While Muslims in New Zealand felt some uncertainties about society's response to them after September 11, the cultural climate is set by state officials and here there was moderation and calm. By way of contrast he points to Australia, where Muslim centres of worship were burnt, "largely because of public utterances over there".

As Musa and many other Muslim observers say, the central issue is the lack of understanding of Islam outside the Muslim world. And also how America, the modernist liberal democracy driving the agenda, perceives itself.

"We understand America so much better than it does us," says 63-year-old Turkish pensioner Yildirin Sakarya. "That's normal because it is a superpower and we are not.

"But then you see, the entire world feels itself a stranger to them. Especially we Muslims."

.

post a comment