Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Lazlo Moholy-Nagy would argue that our eyesight was defective and limited. He would cite the pioneering 19th-century German physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz, who told his students if an optician made a human eye and brought it to him he would say, "This is a clumsy piece of work".

The punchline for Moholy-Nagy would be that we have a better optical instrument than the human eye: the camera.

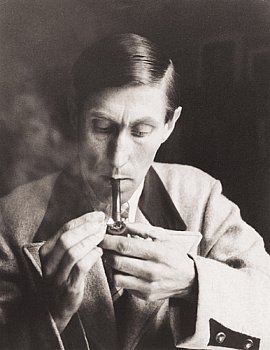

Of course Moholy-Nagy would say that. He was a photographer, although he never referred to himself as one and took few photographs in his life.

Yet Hungarian-born Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) was a crucial figure in the development of photography and was one of the great proponents for it as an art form. And he had a point when speaking of the limitations of the human eye.

The camera can frame an image, freeze time, capture in close-up or offer a vista as vast as the sky. Multiple exposure can evoke movement. The photographic portrait meant society painters packed away their brushes because their skills were redundant. And that was just in Moholy-Nagy's era in the first decades of last century.

Today, photography can also capture motion in various time lapses, take pictures underwater or inside the body, go to the darkest reaches of infinite space, and have its images colourised and manipulated until they are unrecognisable.

Today, more than ever, the camera lies and is a toy which can create art, a democratic tool in which all are equal behind the cheapest disposable.

When Moholy-Nagy advanced his case for "the New Vision" through camera-seeing, he perhaps couldn't foresee how commonplace photography would become. And how common a photograph could be.

Perhaps because of its ubiquity, photography has become a diminished art for most. If anyone can do it, why go to see the pictures of someone who has?

But when photography was in its infancy Moholy-Nagy - designer, painter, sculptor and philosophical polymath - used it to create an art that was distinctive and challenging.

An extensive collection of Bauhaus photographs - some 124 prints by more than 40 photographers - at the Auckland Art Gallery from Saturday is a showcase which includes amateur snapshots alongside the most careful compositions. It profiles the innovations in this influential school where Moholy-Nagy taught for five years until 1928.

As a member of the Bauhaus - the multi-faceted art and design movement founded by architect Walter Gropius, which flourished in Germany between the two world wars - Moholy-Nagy was among the first to experiment with the camera and photographic techniques.

He used the camera and film development tricks to turn the real world into an abstract one. His work was innovative and daring, yet photography was not introduced into the Bauhaus curriculum until after he left.

It was under director Hannes Meyer in 1929 that a photography class was founded at the new Bauhaus in Dessau by Walter Peterhans, whose works were often precise, delicate compositions of diverse material, where meticulous lighting captured textures and form.

However, it had been Moholy-Nagy who advanced photography as a valid form of experimentation and expression and encouraged equally innovative thinkers in the school to explore its potential.

Among them was Lyonel Feininger, whose paintings featuring shafts of tonal light betray an interest in and influence from photography. His son, Andreas Feininger, became one of America's great photographers who produced iconic images of New York in the 40s, penetrating observations of patterns in nature, and 350 photo-essays for Life for 20 years from the mid-40s.

But without Moholy-Nagy's encouragement, cajoling and influence it is arguable that many of these artists would have developed in a different way and we would have seen the 20th century differently. He referred to photography as "the pure design of light".

Moholy-Nagy arrived at the first Bauhaus in Weimar in 1923 and took up the post of director of the metal workshop, where he taught and created sculpture.

Before that, he had experimented with the photogram, a photograph taken without a camera which occurs when an object is placed on photo-sensitised paper and exposed to light.

The image and its shadows emerge on the paper and tone can be achieved by shutting off the light source at any time, or by using translucent or transparent objects, such as glass or fluids.

His arrival at Bauhaus occurred as cracks were appearing in the philosophy Gropius had advanced. Gropius saw the school as one of industrial design, where the arts and industry would merge. Others saw the separate schools within the Bauhaus as constrained by the principle, and some walked.

Moholy-Nagy - who met Gropius some five years earlier and impressed him with his progressive idealism - sided with Gropius and remained there until they resigned in 1928 after political pressure.

During his five years he advanced the cause of photography, which he spoke of as an extension of our limited vision and which supplemented the deficiencies of the naked eye. The camera as aesthetic prosthesis.

But the camera also shapes reality and gets between the viewer and the world. It creates and mediates the world. These were the ideas Moholy-Nagy brought to the Bauhaus and which its fledgling photo-artists explored.

Despite the initial lack of a photographic course, the Bauhaus seems to have been invaded by happy snappers. Outside of experiments and artistic endeavours, Bauhaus students and staff took photographs of daily life, their parties and classes.

A collection of casual Bauhaus snapshots would show some of the great artists and thinkers of last century: the painters Paul Klee, Joseph Albers and Wassily Kandinsky; furniture designer Marcel Breuer; and Herbert Bayer, who worked across the disciplines in typography, sculpture, painting and architecture. And most of them took photographs, too.

One of the most significant figures was Moholy-Nagy's wife Lucia, who was less interested in experimentation but preferred an objective style. Her documentation of Bauhaus life and work was used extensively in Bauhaus publications and in the press, and have played a significant part in confirming the public image of the school.

Out of that diversity of individuals and approaches it is surprising such a thing as "Bauhaus photography" emerged with distinctive and identifiable traits. Yet it did and can often be defined by its unconventional perspective, and sometimes the disconcerting but structured arrangement of object or plays of light.

As might be expected, given the climate in which it was created, some Bauhaus photography has an architectural style. Moholy-Nagy combined image and text into structural forms in the manner of the Russian avant-garde.

Figures and their shadows crossing a courtyard become abstract forms in space; the photomontages and collages often have a diagonal construction.

Bauhaus photography in all its diversity - from snapshots of Gropius at a student party to the most refined and considered images - made a significant contribution to how we greeted the 20th century, and is influencing artists of all persuasions today.

This article first appeared in the New Zealand Herald in June 2003

post a comment