Graham Reid | | 9 min read

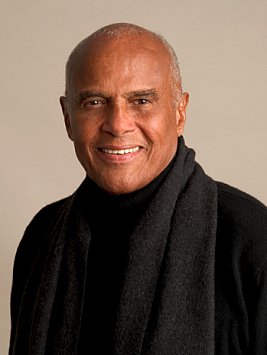

Harry Belafonte’s voice has been his passport. It was his passage out of poverty as a young man and has allowed him access to the hearts of people as he tirelessly articulates the struggle for human rights.

As he stood alongside Dr Martin Luther King, Eleanor Roosevelt and Nelson Mandela as a friend and confidant, his was a compassionate voice for equality, justice and the rights of children.

It was also the voice of The Banana Boat Song, that echo-heavy “day-O“ hit of the mid-50s which people to this day bellow down elevator shafts and in empty parking buildings.

It’s his signature tune and he still performs it, updated with an Afrobeat style and delivered as a celebration of Jamaican resilience.

“I still love that song,” he says, at 73, that honeyed voice sounding rather hoarse and burred around the edges. “That song is about my roots and people who laboured in the banana fields of British absentee landlords. Now, with audience participation, it becomes a celebration of their spirit.”

Despite his years, Belafonte remains an active and influential singer, actor, film director and producer. A newly released collection of his greatest hits - many almost half a century old but distinctive and memorable nonetheless - reminds us just what an appealing singing voice he possesses. It is like liquid velvet on his famous Island in the Sun and Danny Boy, and has a vigorous Caribbean bounce for Matilda! and Jump Down, Spin Around.

Harold George Bellefonte - from Harlem’s ghetto streets, who spent his childhood in Jamaica, served in the Navy during the Second World War and worked as a janitor until he discovered his theatrical skills - was honoured for his social activism by John F. Kennedy, who named him cultural ambassador to the Peace Corps in 1960. The list of honorary awards for his humanitarian activities from African-American and Jewish groups is lengthy. But he has also always been an entertainer.

His singular career dates from acting classes in New York of the 40s, when his classmates included Marlon Brando, Walter Matthau and Rod Steiger, then through the jazz clubs of that city. The backing band for his opening night at the Royal Roost featured friends Miles Davis and Charlie Parker.

His has been a career of entertainment milestones: his album Calypso of 1956 became the first to sell more than a million copies and introduced Caribbean rhythms to an American audience; he starred in Carmen Jones, Otto Preminger‘s 1954 adaptation of the Bizet opera Carmen, and in 1957s Island in the Sun, controversial for its interracial themes; he was the first African-American producer in television; the prime mover behind the USA for Africa programme which led to We Are the World ...

A guiding precept of his life has been the words of his mentor, Paul Robeson: “Art has a purpose of showing the world not as it is, but as it should be.”

Distinguished and handsome even now, Belafonte has blended his show business career with unflagging social work so seamlessly that they progressed in tandem.

It comes as little surprise when he says from New York that he is in a recording studio finishing his latest album, Another Night in the Free World, which mixes African, Caribbean and South American sounds.

Typically, the previous day he was at a United Nations function with actors Susan Sarandon, Danny Glover and Michael Douglas, and “a few Nobel laureates like [author and activist] Nadine Gordimer from South Africa.”

As a UN Goodwill Ambassador since 1987, his priority today is working for UNICEF and lobbying the US Congress to respond to the needs of children through foreign policy. He is just back from a convention for ministers of state from Caribbean and Latin America countries discussing the plight of disadvantaged children in the region, is working with Mandela on the impact of HIV/Aids in Africa, and drumming up votes back home for his choices in the forthcoming elections.

When Belafonte uses that voice on the lecture circuit or to advance one of his many causes, he can be an inspirational speaker, one who imbues his words with gravitas and moral authority. He may possess the politicians‘ proclivity to repeat a resonant, well-polished phrase, but he is not a politician. And that has been his strength.

He profoundly believes that artists who gain a popular platform have more power than most people are willing to acknowledge, and cites Bono from U2 and his recent work with the political establishment to write off Third World debt.

“Because [entertainers] have access to the minds of young people, politicians listen to us. We more often than not represent a force that recognises what young people’s rebellion is about, and are often on that side. We carry a great influence and there’s no question we are sought after because people recognise we have this power.”

With little prompting he expresses frustration with celebrities using their position irresponsibly.

“I‘m enormously saddened by people like Charlton Heston. Instead of gun control and bringing some sanity to the table, he‘s out there making statements with no real regard or sensibility to the enormous anguish and pain that his position causes.

“Those of us who see the world through another prism have a responsibility to make sure that although we defend Mr Heston’s right to say what he says, we must put forth an agenda more stimulating and attractive that opposes where he comes from.”

As one who applauded and supported the hip-hop street culture of young black Americans in the early 80s, he bemoans the rise of gangsta rap, which he says caught him by surprise. “So what we are looking for is how to reasonably deal with this culture and find who we can support in it that makes some positive contribution.”

Belafonte‘s language frequently reverts to the royal “we“, yet as one who stood with King and others during the civil rights struggle of the 60s and beyond, he has a mandate to speak on behalf of the black community, a privilege he doesn’t take lightly.

He acknowledges “despite having been seen everywhere from The Muppet Show to senate hearings” that a younger generation may not be familiar with him, but he has a huge constituency in adult black America.

He dismisses the importance of the divisive Nation of Islam (“its influence is overstated by the press, a story ploughed up when they’ve run out of things to say about the black community“) and says its leader, the Rev Louis Farrakhan, has distanced himself from black Americans.

“The Nation of Islam under Malcolm X at the height of the civil rights movement was a serious player. I don‘t believe Farrakhan carries much influence in our communities. The reason I have sustained an important platform that is recognised and respected, and in some instances solicited, by politicians is that even those who disagree with the position I take never challenge my integrity. I‘m not in pursuit of power.

“People would rather have me on their side than speaking against them,” he says with a low chuckle.

When Belafonte speaks of King - of whose estate he was an executor - the voice adopts a reverential tone. King considered Belafonte a pivotal cultural figure in the struggle for freedom, and Bellefonte - who admits to doubts about the path of non-violence at the time - admires King’s singular vision. Despite strident calls for more direct action at the height of the civil rights movement, King never doubted the effectiveness of non-

violence.

“He made me a believer and his wisdom sits there as a beacon for people to be instructed by. Look at a man like Nelson Mandela, one of the most powerful moral voices in the 20th century. He will tell you non-violence is the only way human beings can begin to even approach a resolve to the problems of this planet”

Belafonte believes there are men and women of destiny given to the world: “It‘s the only thing that makes me hopeful,” he laughs, but then agrees that ethics are often abandoned in favour of expediency.

“Oh God, just look at global leadership. And politically, America is in a shambles. Never have I seen such a shoddy bunch of politicians running for office as we have today. I think they resist a moral agenda because it requires that they do something.

“It is imperative for them and what they have set as their agenda that they do not have a moral component. That would force them to be too responsible.”

As a longtime Democrat he will vote for Al Gore - “albeit with not as much enthusiasm as I would want“ - but says the national dialogue in the run-up to the presidential elections has been disgracefully trivial.

Experience, however, tells him real power is not vested in presidents, so he uses his cachet behind the scenes with “men who sit at the head of important committees where legislation is reversed or advanced according to their wishes.”

Yet despite his best efforts, the world seems as riven with ignorance and mistrust as ever. “Yes, I do feel great frustration,” says the voice, sounding suddenly weary. “I certainly felt by this and humankind would have come to its senses, that we‘d gone past the primitive state of bombing one another to death. I thought the world would have yielded much more readily to the sanity we sought to bring by our involvement.”

And when politicians stand beside him in the hope that some of his lustre rubs off, what prevents him from becoming cynical?

“I grew up in poverty but my generation was filled with enormous activism, first against Hitler to defeat fascism. So I saw what we were capable of doing.”

He refers again to King and how his message reached around the world, especially Africans emerging from the shadow of colonialism.

“His power, grace and wisdom changed so much and people everywhere were motivated by what Dr King and African-Americans achieved. We showed great achievements were possible. So I believe cynicism is a great enemy, a cop-out.

“If you are cynical you don’t have to do anything.

“I‘ve never been cynical.”

post a comment