Graham Reid | | 2 min read

Popular culture loves nothing so much as the early death of an obvious talent. We are left with questions and the speculation on just what direction the gift might have moved in had the artist lived.

Some of that discussion will doubtless be aired with the Auckland exhibition of works by Thames-born painter Rhona Haszard, who fell to her death from the fourth storey of a tower in Egypt in 1931. It appears she committed suicide. She was 30.

Curated by Dr Joanne Drayton of Dunedin, who followed the footsteps of the artist through Europe and Egypt while researching a biography, the exhibition of works illuminates the life of this little-known artist whose works are usually scattered through a number of New Zealand collections.

Two years after Haszard's death, an exhibition collated by her husband toured New Zealand galleries, but that was the last time a substantive body of her work was before the public.

Yet while her paintings will be acknowledged for their innovative style and elements from the European movements of her time, it is hard to deny her short but dramatic life is equally interesting.

Haszard was perhaps wise to move from the cloisters of New Zealand in the 30s - her young life was already fraught with a small scandal.

After an itinerant childhood during which she lived in Auckland, Christchurch, Hokitika and Invercargill, she enrolled at the Canterbury College of Art during what, in retrospect, seems like an annus mirabilis for women artists. Her classmates were the painters Evelyn Page, Rata Lovell-Smith and Olivia Spencer Bower, and the artist-novelist-playwright Ngaio Marsh.

In 1921, Haszard became a member of the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts. In 1922, she exhibited with the Canterbury and Auckland art societies. She seemed settled for the rare security of life as an artist when she married her fellow student and part-time tutor Ronald McKenzie.

But within three years, in 1925, she had fallen for the romantic and well-travelled English ex-Army officer Leslie Greener and they prepared to elope. On the eve of their departure Haszard's father stopped them, and the unhappy couple had to remain in the country until their marriage was formalised.

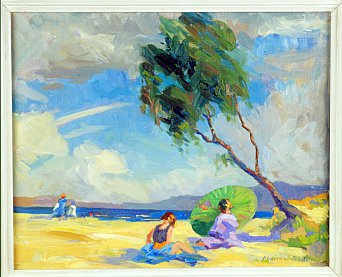

The pair left for Sark in the Channel Islands the following year where his parents lived, then went to France. It was during this period her style changed markedly into the post-impressionism she is renowned for.

With her husband, who is generally considered a lesser talent, she studied briefly at the Academie Julian in Paris and painted in the Marne valley.

Her works became imbued with a stillness and light, as is evident in her landscape studies (most of which are bereft of human life) with their pastel tones and bright areas of sharp sunlight.

The forms are flattened and constructed in a style which is broken into what some commentators have called a mosaic style. This is evident in paintings such as The Marne Valley (1927) and the especially muted and moving Mosque at Sidi Bishr (1930).

Haszard was recognised in France and Britain, and the same year she received a bronze medal at an exhibition at Wembley she also exhibited in the Salon of the Societe des Artistes Francais in Paris.

Her works appeared in showings by the Society of Women Artists in London, and at exhibitions in Manchester, Leeds, Bradford and Glasgow.

She was widely feted, but a back injury during a trip to Cyprus forced a trip to London for treatment. She engaged in a love affair, continued to paint and exhibit, then she and her husband went to Egypt, at the time a playground for the monied bohemians of Europe.

By the time she arrived in Alexandria in her late 20s she was the thoroughly modern Haszard and, as such, challenged genteel sensibilities.

She became an advocate of vegetarianism and dressed eccentrically, extolled Radclyffe Hall's lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness and, most pointedly, spoke in favour of de facto relationships.

Haszard was a woman of her intellectual milieu. Yet during her stay in London she was in physical pain and suffered from depression. Her gaiety may have masked some deeper unhappiness which was not evident in her bright and sometimes stark work which, in some instances, have elements of an understanding of Cubism.

What direction her art would have taken her as she stood on the cusp of her 30s we will never know.

The day after an exhibition of her work opened in Alexandria, Rhona Haszard climbed a tower at Victoria College where she and her husband lived and taught, and plunged to her death.

post a comment