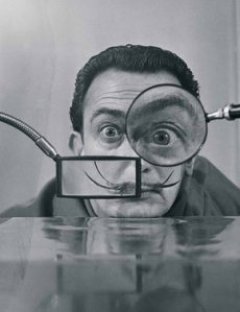

Graham Reid | | 10 min read

Of all the monuments a man has built to himself few, if any, are more bizarre than the grand conceit Salvador Dali designed in a burned-out theatre in his birthplace of Figueres.

A little more than an hour north of Barcelona by local bus, Figueres is a modest, not especially interesting town of some 35,000 people. But it is the traditional commercial centre of the plains of Ampurdan which stretches across northern Catalonia to the base of the Pyrenees. It is described with an apparent lack of charity by one guide to Spain as “humdrum (some might say a dive) with a single attraction: Salvador Dali”.

Searching for its other highlights -- there is Spain’s only toy museum apparently, but it was closed when I tried it -- means tramping its light industrial and unglamorous streets. The guidebook assessment is quickly confirmed.

There is a wall plaque on Dali’s birthplace at 20 Calle de Monturiol but it hardly seems worth the photo. On the opposite side is another which notes that both Dali and writer Carles Fages de Climent (1902-68) were born in this street, named for another illustrious son of Figueres, Narcis Monturiol who invented the submarine.

And that’s about it. There’s no submarine museum.

The Rambla in the centre of town is pleasant enough on a sunny day -- I give some euros to a couple of annoying itinerants to make them go away -- but the books are right. It’s only Dali.

But that’s more than enough.

The artist was born here on May 11 1904 and maintained a peculiar affection for this humble place, although he spent much of his life at the coastal village of Port Lligat just 15 beyond nearby Cadaques, his father’s hometown.

It was at Port Lligat that Dali and his wife Gala -- formerly the wife of the poet Paul Eluard -- gradually acquired fishermen’s cottages and linked them together to create a sprawling house and the studio where he painted some of his most powerful works notably his famously inverted Christ of St John of The Cross. Completed in 1951, it currently hangs in the Glasgow Art Gallery.

But it was to his birthplace that Dali returned late in life and where he chose to create his monument. And quite some affair it is.

The exterior of the Teatro-Museo Dali is covered in geometrically placed reproductions of the local bread rolls, and the roof is surmounted by large eggs and what look like gold-painted artists’ mannequins.

The exterior of the Teatro-Museo Dali is covered in geometrically placed reproductions of the local bread rolls, and the roof is surmounted by large eggs and what look like gold-painted artists’ mannequins.

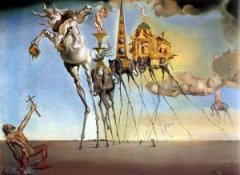

Inside however it is treasure house of Dali’s paintings, drawings, constructions and holograms (as realised by other artists). There are juxtapositions of eye-jerking dimensions -- like a sculptural copy of Michelangelo’s Moses with a giant squid, which probably only ever made sense to the artist. And maybe not even to him.

The central courtyard is given over to a reconstruction of a piece he did in New York involving a classic Cadillac allegedly once owned by Al Capone (inside which rain falls on the shop mannequin passengers at the press of a button) and a tower of car tyres with a fishing boat on top. The sound you hear is of people scratching their heads.

But as a disorienting entrée into Dali’s strange world of surrealism it is perfect.

The extensive galleries however contain some works of exceptional (albeit strange) beauty. An unexpected bonus is his personal art collection which includes works by El Greco, Duchamp and Meissonnier. Up a stairwell, but largely unnoticed by tourists and school groups negotiating their way to further psychic confusion, is a collection of Piranesi’s I Caceri series of massive and oppressive prisons.

But it is Dali’s art that engages the eye and baffles the brain: there is a room which reconstructs his portrait of Mae West as a ruby-red, lip-shaped couch between two wall paintings (her eyes) and a fireplace (her nose). On first sight it is simply another room of scattered oddities, but climb the stairs and peer through a lens and it reveals itself as a 3D “painting“, as does the abstract of Gala on the far wall of the foyer which turns itself into Abraham Lincoln when you feed coins into the telescope opposite. A crowd of young school children hoot with delight at the changeling image although one wonders how their teacher explains a long-dead American president to excitable 10-year old Spanish kids. I give them euros and watch them enjoy the image all over again.

There are similar visual games everywhere -- the small hologram of a seated Alice Cooper, a late visitor to Dali when the artist was in high fraud phase of his long life -- is impressive.

With the centenary of his birth Figueres experienced an influx of visitors to this shrine of the strange.

With the centenary of his birth Figueres experienced an influx of visitors to this shrine of the strange.

Understandably there was renewed curiosity about the clown prince of surrealism who died in this museum and is buried in a room below.

Of course there is a museum shop selling every kind of Dali memorabilia and merchandising from tea towels and shot glasses, to posters and models of soft watches. This is a museum as money-go-round.

But it is fitting too because Dali was always a commercial proposition: he designed advertisements and shop-window displays and in the 60s signed thousands of blank pieces of paper which were used for lithographs he never inspected. There were thousands of “limited editions” and, inevitably, his signature was forged on some prints. At the peak of his fame his genuine signature on a blank sheet was worth $100,000.

Then there is the knotty matter of the artist Manuel Pujol Baladas who churned out dozens, and possibly hundreds, of Dali pastiches. He claimed that Gala, who took to signing contracts for her husband in the 80s, had encouraged him. In the mid 80s it was estimated there might have been $1.5 billion worth of fakes in circulation, and Dali didn’t disapprove.

Not for nothing did a rival observe that an anagram of his name was “avida dollars”: “greedy for dollars”.

However the centenary of his birth afforded the opportunity to reconsider Dali the Artist -- accepting that Dali the Professional Eccentric and Dali the Charlatan stand as an unholy trinity.

His decline can be charted in the pages of Time magazine: in 1936 he was on the cover and being admired for his technical ability, although the magazine also noted Dali’s “facility for publicity which could turn any circus press agent green with envy”. Nine years later the magazine was calling him “a slick painter and calculating showman who has made surrealism into a lucrative sideshow”.

By the early 70s he was being feted by John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Sonny and Cher, the Warhol crew, and others at the art-chic end of the rock circuit. And was supervising a spread of nudes and recycled images of his better work for Playboy.

When asked to explain what they meant he boasted, “The meaning of my work is the motivation that is the purest -- money.”

Dali was always given to grandiose pronouncements designed to shock and provoke. At 23, when he came up for his examination at the School of Fine Arts in Madrid, he refused to be questioned for his oral exam.

“I am very sorry,” he announced. “But I am infinitely more intelligent than these three professors and I therefore refuse to be examined by them. I know this subject much too well.”

“I am very sorry,” he announced. “But I am infinitely more intelligent than these three professors and I therefore refuse to be examined by them. I know this subject much too well.”

Dali did know his art history -- whether better than those professors we cannot tell -- and in his paintings he quoted from Meissonnier, Velasquez and especially Millet whose religious work The Angelus he referred to repeatedly, sometimes charging it with secular eroticism.

From Zurbaran he drew the influence for his inverted Christ, and he evoked Goya in his painting The Exterminating Angel and the film L’Age d’Or which he made with Luis Bunuel. He studied Vermeer (he sat in the Louvre and copied his paintings) and much of his early work grew out of de Chirico’s illusionist style. In Bosch he found a kindred spirit and source material.

One of his greatest influences was the Catalan architect Gaudi, whose conception of the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona as an organic object referred to the geology of the region, notably around Cadaques with which Dali was familiar.

Art critic Robert Hughes considers Dali to be “the best surrealist painter”, although that may need some qualification: he means in the technical sense and as a draughtsman unparalleled by his peers.

Dali’s work --evident in his portraits of his beloved Gala through the decades -- possess the photographic detail of a Pre-Raphaelite. His rapid ink illustrations for Don Quixote are brilliantly evocative and the jewellery displayed in his museum is exceptional, made from gold coins with the faces of Dali and Gala on them.

But his artistic career went haywire because of the greed within the Dali-Gala enterprise: he marketed himself mercilessly from the 40s and was consequently held in contempt by his colleagues and the art establishment. In that he anticipated Warhol who also turned art into commerce, although in the cooler mood of New York in the 60s Warhol felt no need to act the dandy buffoon to get media attention.

But his artistic career went haywire because of the greed within the Dali-Gala enterprise: he marketed himself mercilessly from the 40s and was consequently held in contempt by his colleagues and the art establishment. In that he anticipated Warhol who also turned art into commerce, although in the cooler mood of New York in the 60s Warhol felt no need to act the dandy buffoon to get media attention.

And so Dali, artist and person, went into a steady decline even as his wealth grew.

Hs tomb downstairs set into the wall is modest, although his real monument is the Teatro-Museo surrounding it.

There was controversy within the Dali cabal as to where he should be buried. He wanted to be beside his late wife but wiser heads -- knowing his commercial value even in death -- decided to entomb him here. There was also the argument that Dali and Gala had long been estranged anyway.

In 1970 Dali gave his wife the Castell de Pubol near Girona which he had bought. She moved in and remained there until her death in 1982. Dali never visited unless she summoned him and Gala entertained a stream of young lovers to fulfil her sexual desires -- which need not be gone into here. (Caution: contains very adult themes.)

Dali was also prone to sexual strangeness: he painted The Great Masturbator and said he often exercised himself in this way, sometimes three times a day. He enjoyed fetish objects and women’s shoes.

But after Gala’s death the old man -- in his late seventies and surrounded by sycophants and business advisors -- briefly moved to her castle where he became a recluse and refused to eat. A fire in his bedroom left him severely burned and frail. Weighing only 45 kilos, he moved back to his self-created monument in Figueres and lived in a tower that he renamed Torre Galatea in memory of his wife.

But after Gala’s death the old man -- in his late seventies and surrounded by sycophants and business advisors -- briefly moved to her castle where he became a recluse and refused to eat. A fire in his bedroom left him severely burned and frail. Weighing only 45 kilos, he moved back to his self-created monument in Figueres and lived in a tower that he renamed Torre Galatea in memory of his wife.

He remained there, seldom seen by anyone, but supervising the creation of this museum, until his death in January 1989.

Today the Dali museum’s turnover and income from the reproduction of his works -- not to mention notepads, address books and so on that are flogged over the internet -- provide a cash flow that may be his lasting legacy.

His artistic legacy is harder to assess. Certainly he sold himself out for handfuls of silver, his surrealism became increasingly mannered and fraudulent, his religious works from the 50s of variable merit and integrity.

Yet when confronted with the breadth of his work in his museum you cannot deny he was a gifted artist: his dark self-portrait when he was only 17; the many portraits of Gala; the landscapes of Spain rendered in quick and confident lines; the curious visions which pervade the scenes …

If there is an unacknowledged aspect to Dali it is that he was a true Renaissance artist. He was curious about molecular structure and holograms. He made films with Bunuel and designed a nightmare sequence for Hitchcock’s Spellbound. He collaborated with Schiaparelli and Chanel on fashion objects; designed the backdrops and sets for ballets; worked in theatre; did advertising posters; was a book illustrator and the author of an unreadable novel.

Dali was a strange and complex man: he had the skills of a fine draughtsman and colourist and an acute eye for visual juxtapositions, but was also possessed by a Hollywood actor‘s need for the lifeblood of publicity, and the huckster’s lust for money.

Dali was a strange and complex man: he had the skills of a fine draughtsman and colourist and an acute eye for visual juxtapositions, but was also possessed by a Hollywood actor‘s need for the lifeblood of publicity, and the huckster’s lust for money.

He was born middle-class with all the snobbery and upward aspiration it could bring: “At the age of six I wanted to be a cook. At seven I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing ever since,” he wrote in one of his many books, The Secret Life of Salvador Dali.

It was typically outrageous boast from a man who also penned the immodestly titled Diary of a Genius.

The intrinsic value of much of his art has been subverted by such outrages. He courted the extremes, embraced fascism and Franco, had a live tortoise with an ashtray stand on its back crawling around his home in Port Lligat, made a chair out of an elephant’s skull, and turned every act and artefact into a commercial proposition.

He was profligate of his genius, and died alone.

If on the centenary of his birth the curators of the museum in Figueres had started burning giraffes in his honour it would not have been inappropriate. Crass perhaps, but Dali was never one for the subtle gesture.

This was a man who wrote a limited-edition cookbook in which he said that woodcock cooked in its own excrement “will always remain for me, in that serious art that is gastronomy, the most delicate symbol of true civilisation”. Typical.

Shit, masturbation, repressed sexuality -- alongside feverish Catholicism -- were among Dali’s obsessions. They are all, and then some, represented in his strange museum.

He once proclaimed, “The only difference between a madman and myself is I am not mad”. He may well have been right, you can judge for yourself in Figueres.

If you are in Barcelona and have a spare day, take the local bus up to his birthplace for an enlightening and entertaining day in Dali’s homage to himself.

Wear an aqualung, be carried on a litter borne by bare-breasted Amazonian women and take an iguana on a leash -- and you’ll still feel tediously normal in Dali-world, the Disneyland of the disturbed.

This is a chapter from Postcards From Elsewhere, winner of the 2006 Whitcoulls Travel Book of the Year award.

post a comment