Graham Reid | | 9 min read

Gorecki: String Quartet #2 Opus 64, Il Deciso: Kronos Quartet

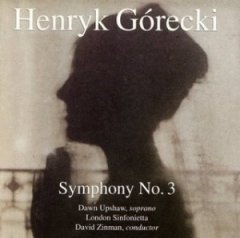

When Billboard magazine – the bible of the international music industry – put classical music on its cover in September '92 with the heading “It’s Cool Again!” there was only one mention of Polish composer Henryk Gorecki in the 18-page insert supplement.

And that reference was only to say that despite a stagnant market (unit sales in Britain down 20 per cent compared with the same quarter the previous year) meaning that many classical labels were cutting back on their catalogues, some new music was getting released, such as Gorecki’s Symphony No 3.

What could not be anticipated at that time would be the runaway sales success of this grim, moving symphony and how much it would activate that stagnant market.

Within a matter of months the album had settled itself at the top of the classical charts in Britain and become the first contemporary orchestral recording to enter the pop charts, where it peaked in January at No 6.

Within a year it went on to become the biggest selling classical album in America and its reclusive composer had endured his first press conferences.

Gorecki – who lived in the oppressively polluted town of Katowice near Auschwitz – was an unlikely candidate for such attention.

Until Symphony N. 3, widely known as The Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, he had not spoken to the media in Poland since for over a decade and, according to the Observer at the time “seems not to have given an interview for 20 years.”

As one article pointed out in the argot of pop culture into which the reluctant Gorecki found himself: “He wasn’t touring the UK. He wasn’t on television. He wasn’t being heavily marketed or playing a familiar all-time classic. Dammit, his Symphony No 3 wasn’t even featured in a Levi’s ad or sweetening the end credits of a Kevin Costner movie.”

Funny, but not entirely true as it turned out.

The piece – sung by soprano Dawn Upshaw with the London Sinfonietta conducted by David Zinman – captured imaginations with its understated power and harrowingly simple lyrics partly based with poems written by a woman in a concentration camp.

If the sheer humanness of Symphony No 3 was its appeal it took the record company Warners by surprise, although it certainly did its part in the promotion.

“We loved the music when we heard it at the recording session, that’s why we were happy to release it,” said Warner’s classics general manager in Britain, Bill Holland. “By the time we had the silver disc made up it had gone gold.”

The piece, “without a big name, by a man with an unpronounceable one,” as the Sunday Telegraph had it, was selling 2000 copies a day in Britain during January 92 and Gorecki (pronounced Gor-estz-kee) was reported to be both delighted and mystified that -- 16 years after his symphony had been written, six years after it had finally found a publisher and on its fourth recording -- it had at last found an audience.

The piece, “without a big name, by a man with an unpronounceable one,” as the Sunday Telegraph had it, was selling 2000 copies a day in Britain during January 92 and Gorecki (pronounced Gor-estz-kee) was reported to be both delighted and mystified that -- 16 years after his symphony had been written, six years after it had finally found a publisher and on its fourth recording -- it had at last found an audience.

“It has become a real cult record,” said Warners man Holland in March. But there was much more to it than that, and critics and musicologists were lining up to suggest reasons why an austere, haunting slow piece should say something to an audience in the last days of the 20th century.

To explain that, and what has been called “the holy minimalism” of this contemplative piece, attention inevitably turned to Gorecki himself – an intense intellectual who said he wrote as a witness and with a warning.

Growing up near Auschwitz and living through the repressive Polish regime shaped his life; being a product of the Polish avant-garde movement in the late 50s shaped his music.

Gorecki, 60 when the album took off and today, was born in Silesia in Poland’s southern coal-mining belt and grew up in Katovice where he still lived with his wife Jadwiga, to whom the work is dedicated.

As journalist Johnny Black noted, “the published facts about him are as minimal as his music.”

He had two children – his son a student composer, his daughter a graduate pianist -- and was once a schoolteacher. After two years in the classroom he enrolled as a composition student at the State Higher School of Music.

But it would be wrong to see Gorecki as a remote, monastic type whose music is brooding and irredeemably melancholy. On a visit to London he was ebullient, volatile and argumentative, according to the Observer’s Nicholas Kenyon who spent some time with him.

That perhaps explains his early work. In 1958 he sent a shockwave through the staid post-Stalinist music world with a debut piece called Epitaph which drew from the works of Stockhausen, Webern and Messiaen, all composers previously outlawed.

His single-minded pursuit of music with high ideals continued. “I hate commerce in music,” he once said. “I am not interested in career.”

In 1963, angered by the establishment’s accusation that he couldn’t write a decent tune and had therefore opted of the apparently undisciplined work of the avant-garde, Gorecki wrote Three Pieces in Olden Style which drew on his passion for traditional folk music.

Outside his native Poland Gorecki was seldom heard. His name appeared in very few Western biographies of composers and, aside from a brief study period in Paris in the early 60s, he rarely moved far from the polluted skies of Katowice.

His work and reputation, such as it has been, was overshadowed in the West by Krzyst of Penderecki and Witold Lutoslawski.

Why then had his impossibly slow, lyrically simple Symphony No 3 taken off?

In a word – and one Gorecki doubtless found objectionable – marketing.

What Holland from Warners recognised as being needed to sell the album was “the listening experience,” so he sent 300 copies to a target market.

“We decided to do a full-scale mail out not to the music critics but to tastemakers who might be able to spread the word of mouth.”

Copies of Symphony No 3 were sent to rock stars with classical inclinations; Paul McCartney, whose Liverpool Oratorio had just been performed; Elvis Costello who was recording with the Brodsky Quartet; and key figures in the British Polish community.

“There was a Catholic connection, so we sent it to Cardinal Hume. It was political, so we sent it to [former Prime Minister and conductor] Edward Heath. Everyone got a little note that said ’please listen and, if you like it, tell your friends’.”

Among those in receipt of the album and telling their friends were Irish singer Enya and Mick Hucknall, singer with the pop band Simply Red.

The album’s release coincided neatly with the launch of Classic FM radio in Britain and by January of 93, six months after it release, the album hit the top of the classical charts.

Major newspapers ran features on “Gorecki who?” And some asked the question: if this is his third symphony, what happened to the other two?

Despite the acclaim – and sales figures - the Polish composer whose work reignited the shaky classical market remained largely unmoved by it all. “I would rather die poor and be remembered as a genius than be called a genius now and forgotten when I am dead.”

But not everyone attributed genius to him.

In a letter to the Guardian, composer Fritz Spiegl said that Symphony No 3 was suitable only for the “the musically illiterate” and that the subtitle was “syrupy emotional.”

Others have dismissed it as “wallpaper” and attribute its success to a few minutes of the music appearing as the end-title scene of a French film Police (starring Gerard Depardieu) which was screened on British television over Christmas in 92.

That, the argument goes, took the work to a middlebrow audience more at home with Enya’s wispy Celtic tonalism than to the intelligent, discerning classical buyer.

The elitism and arrogance of that argument perhaps need not be addressed.

Despite the few ill-disposed critics, Symphony No 3 became the classical album of 92. Wire magazine accorded it best modern composition; it was record of the year in the Independent and CD Classics magazine; it was sold in national retail chains throughout Britain and had two Grammy nominations (classical recording of the year, best orchestral performance); and in America it was named record of the year by Stereo Review and Time.

Despite the few ill-disposed critics, Symphony No 3 became the classical album of 92. Wire magazine accorded it best modern composition; it was record of the year in the Independent and CD Classics magazine; it was sold in national retail chains throughout Britain and had two Grammy nominations (classical recording of the year, best orchestral performance); and in America it was named record of the year by Stereo Review and Time.

In New Zealand it was a steady seller and appeared on the lower reaches of the national sales charts in early May 93 – without any promotion.

The appetite for Gorecki’s other work was whetted and given impetus by an extraordinary Tony Palmer documentary and interview on the South Bank Show, screened in Britain in early April 93.

Henryk Gorecki – little known a year before – was suddenly hip and found his music played alongside fashionable New Yorkers such as Philip Glass and Steve Reich on New York radio stations.

His square-jawed, heavy-browed look stared out from magazines and record companies, anxious to capitalise on his marketability, released or re-released other works.

And he was “canonised by the cult leaders of contemporary trends, the Kronos Quartet,” as the Observer noted.

To be fair to the designer-chic Kronos - whose previous albums included jazz, rock and avant-garde works -- they first performed Gorecki’s Already It Is Dusk in 1989 and it was commissioned by them from Gorecki long before he was enjoying a high profile.

That taut (and previously released) 15-minute work appears with another Gorecki string quartet composition from 1990, Quasi Una Fantasia, on the Kronos’ 93 album and offered another, more vigorous, side of Gorecki’s music.

Interestingly, too, what reception Gorecki’s music found in the American minimalist school to which it was – quite wrongly – compared.

Steve Reich didn’t like it but John Adams championed it and four years ago was premiering Gorecki’s Harpsichord Concerto.

While Holland of Warner Classics UK said there were no plans to release either of the first two symphonies (“totally unlike No 3” he said, a comment which reinforced the belief he was a shrewd marketer), a number of the Gorecki works were quickly available, all illustrating the composer’s distinctive style.

Most notable is the O Domina Nostra duet for soprano and organ released on the ECM New Series, a label – like Warner’s Elektra Nonesuch on which the Kronos and Symphony No 3 albums appear – was established specifically to record contemporary classical music.

O Domina Nostra best conforms to that “holy minimalism” description as a work of sublime, moving religiosity yet also astonishingly spare.

As one critic observed of Gorecki’s scores, they “don’t look like much, just a few notes per page, with rhythms and melodies appearing to be schoolboy simple.”

Yet is that simplicity of musical expression and emotion which captured the imagination. As the South Bank Show film of Gorecki/Katowice/Auschwitz showed with almost harrowing intensity, to confront the images so the 20th century is to run headlong into an impenetrable sadness and incomprehension.

How do we explain the gas chambers and Stalin’s purges? Where to find comfort during the long darkness of oppression?

Gorecki’s answer, although he was adamant he was not a religious composer, is in faith. He was deeply influenced by church music – O Domina Nostra is nothing if not holy – and Beatus Vir, composed for Pope John Paul II and commissioned for the 900th anniversary of the martyrdom of St Stanislaw, was released in early 93.

The work was premiered by Gorecki in 1979 but only belatedly appeared on disc along with Old Polish Music.

Although liturgical references provide a key to Gorecki’s music, he insisted folk music was the theme of all his work, not tunes so the audience could recognise them but so that if they had their eyes closed they could smell them.

And it was that inexplicable emotional quality which set Gorecki apart and gave his work a mysterious, meditative and incantation quality.

“It became music about the essence of music,” said critic Mark Swed, explaining Gorecki’s shift from radical avant-garde to the slow drama of his work of the time.

“[It is] as if the composer has taken a microscope to just a beat or two of his earlier complex music and seen how, when greatly magnified, unsuspected richness of tone and texture could be found.

“What Gorecki found was a way to put on disc something that every musician knows as a personal experience but that is exceedingly difficult to share with an audience.

“It is the moment when a musician loses his own psyche in tone.”

Henryk Gorecki died in November 2010 in Katowice. He was 76.

post a comment