Graham Reid | | 8 min read

John Moran: Subject: The Beatles

When the recording of Robert Moran’s new opera was released in '94 there was an almost predictable ripple of controversy in the more staid sections of the classical world. And not because this dark, disconcerting piece offered no conventional narrative structure, that one of the performers was proto-punk Iggy Pop (who spoke his part anyway), or that substantial sections of the music were pastiches of Beatles tunes.

People could almost live with that.

It was the subject matter that got the laptops and ballpoints at work.

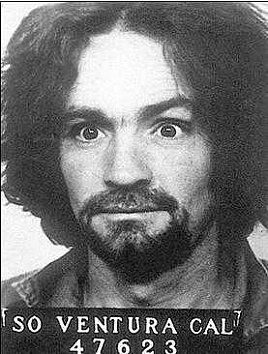

Moran’s work was The Manson Family, a contemporary piece about the murderous actions of Charlie, Squeaky, Susan, Sleazy, Grumpy and Doc . . . or whoever they were in that family that played together and stayed together.

Yet while a few critics were repulsed by the subject matter -– there was no madness, murder or mayhem in Lucia di Lammermoor, right? –- others hailed Moran’s work as a courageous breakthrough and unique blend of traditional and contemporary styles.

The Manson Family (“representatives of the same archetypes you find in Greek tragedy,” insisted the 27-year-old composer loftily) is an anxious sonic nightmare full of chilling and relentlessly stalking piano, cross-cut cellos, motorcycles racing from speaker to speaker, and psychedelics gone sour.

Moran also used studio technology to sample voices and Beatles references of the kind which inspired the mad Manson during his brief circus of mayhem in the late Sixties. But was it an opera for the anyone-for-tenors audience “where a guy gets stabbed and instead of bleeding he sings,” as critic Ed Gardiner said?

Maybe not.

With The Manson Family and a dozen other similarly challenging works in the past decade, classical music has come a long way from Kansas, Dorothy. And there’s no going home.

Yesterday’s marginalised minimalists are now in the mainstream and composers such as Michael Nyman – best known at the time for his soundtracks to Peter Greenaway’s films -- are scoring shampoo commercials.

The contemporary composer of today is less stuffy than those of old and the music likely to have titles such as Nixon in China (John Adam’s “modern equivalent of Handelian heroic comedy” according to one critic), 1000 Airplanes on the Roof, (by Philip Glass and David Henry Hwang) or Einstein on the Beach (by Robert Wilson).

Everything odd, somewhere even odder, in fact . . . and drawing on diverse contemporary sources.

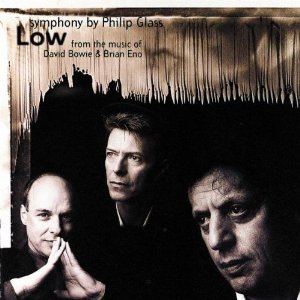

Glass’ work The Low Symphony was based on music from David Bowie’s 1977 Low album recorded when avant-garde rock artists and contemporary classical musicians were wearing remarkably similar trousers.

Glass’ work The Low Symphony was based on music from David Bowie’s 1977 Low album recorded when avant-garde rock artists and contemporary classical musicians were wearing remarkably similar trousers.

On record shop shelves in either classical or rock categories – are albums by the Balanescu Quartet featuring interpretations of pieces written by Moran, former Talking Head frontman David Byrne and, more spectacularly unexpected, music by Kraftwerk, German exponents of the hard-edged synthesised techno-industrial rock.

The Brodski Quartet collaborates with rock singer-songwriter Elvis Costello on The Juliet Letters, The Turtle Island String Quartet plays jazz compositions, and you know times have changed by the very title of Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Three Screaming Poppas.

It’s classical Jim, but not as we know it.

And even opera these days isn’t just sung in "foreign" like Carreras, Domingo and that guy Maserati. It’s in English and as up to date as a newspaper headline from the foreign desk.

John Adams’ majestic if flawed The Death of Klinghoffer – with the orchestra of the Opera de Lyon conducted by Kent Nagano – told the story of the 1985 murder of the wheelchair-bound Jewish passenger John Klinghoffer when the cruise liner Achille Lauro was hijacked by Palestinian terrorists.

Here was material for a drama of the personal and political – and of majestic proportions, offering a chorus of exiled Jews and Palestinians, passions and tensions of the shipboard events and a long lament of a grieving widow.

This was opera for the CNN generation.

As the booklet accompanying the double disc noted, Adams began writing Klinghoffer when “the United States was lavishly supporting Saddam Hussein [in 1989] and completed it on February 12, 1991, while we were dropping “smart bombs” down Baghdad ventilator shafts.”

And despite the shortcomings of the libretto by Alice Goodman (“Who could fill a decade’s worth of Pseud’s Corner with this single text,” said critic Hugh Canning, perhaps a little harshly) here was a piece of music theatre which left Chess, Les Miserables and Miss Saigon for dead.

Yet it was also quite traditional in many respects and has a construction resembling “a Handelian opera in its juxtaposition of aria and choral commentary,” according to Canning.

Few operatic works could have been more timely than that by jazz pianist/composer Anthony Davis, whose The Life and Times of Malcolm X arrives alongside the Spike Lee X movie and its trickle-down marketing of T-shirts, baseball caps and bomber jackets.

To give Davis – and his cousin, the poet/novelist/journalist and libretto writer Thulani Davis – his due, this X was originally written in 1985 and it was only almost a decade later that it had recording release as a two CD set with performances by its original singers and the Orchestra of St Luke’s conducted by William Henry Curry.

To give Davis – and his cousin, the poet/novelist/journalist and libretto writer Thulani Davis – his due, this X was originally written in 1985 and it was only almost a decade later that it had recording release as a two CD set with performances by its original singers and the Orchestra of St Luke’s conducted by William Henry Curry.

Anthony Davis – whose classical works embrace violin sonatas, brass quintets and choral works – saw his X as no less timely, in fact more so, for the long delay between its acclaimed premier in 1986 and eventual record release.

“The movie liberates us. When we did X in '85 there was so much information we had to give people. I remember my producer in Philadelphia asking ‘The Fruit of Islam, what’s that?’ because he didn’t have a frame of reference.

“Now people know so much more about Malcolm X that we might be able to do a much more expressionistic version.

“But the one thing that’s fun with opera is that you’re so detached from real life to begin with – the form itself is so absurd that gives you freedom.”

Freedom, of course is always there for the taking as the designer-chic Kronos Quartet showed.

Their album Short Stories of '93 -- the year before Moran's Manson album was released --opened with percussive chatter on Digital (written by avant garde rock guitarist Eliot Sharpe), moved through the Willie Dixon blues standard Spoonful, took in the downtown New York avant-jazzer John Zorn’s cartoonish and busy Cat O’Nine Tails (Tex Avery Directs the Marquis de Sade) and went out with a piece written by Indian vocalist Pandit Pran Nath, his most visible disciple being minimalist La Monte Young whose magnum opus was The Well-Tuned Piano, a continuous five-hour piano performance piece.

That ambitious kaleidoscope of styles is no less than Kronos followers have come to expect.

This group, which is dedicated to performing works of 20th, and now of course 21st, century composers, has performed material by Jimi Hendrix, Alfred Schnittke, jazz saxophonist/composer Ornette Coleman and – in a studio concert – played alongside the late Charles Ives by using retrieved tapes much in the way rock musicians have done since the Beatles’ Revolution in 1968.

Increasingly classical composers and musicians have discovered the studio as an instrument in itself. Violinist Gidon Kremer’s album of music by Luigi Nono (1924-90) is a work of co-invention rather than a performer playing a composition.

Nono deliberately didn’t finish writing the piece until minutes before Kremer played it so the performer’s task was one of discovery and interpretation - as much as one can interpret a work which allows for studio noise as the violinist moves between various music stands, and accepts accompanying sound tapes and electronic effects.

Despite what might have traditionally seemed limitations, the Nono/Kremer disc (on the mostly staid Deutsche Gramophone label) is a remarkably lively, evocative work.

Working with tapes and cut-ups is very much the provenance of one-time minimalist Steve Reich whose Different Trains in 1988 linked his Jewish New York childhood of catching trains between the homes of his separated parents with the Holocaust trains in Germany of the same period.

Working with tapes and cut-ups is very much the provenance of one-time minimalist Steve Reich whose Different Trains in 1988 linked his Jewish New York childhood of catching trains between the homes of his separated parents with the Holocaust trains in Germany of the same period.

Reich used recorded speech from the period alongside musical repetitions of the speech patterns as played by the Kronos Quartet.

Reich, Kronos, Glass and, to a lesser extent, Michael Nyman (who composed music for the Jane Campion movie The Piano) awee part of a new breed of classical performers.

They are articulate, astute, marketable and – perhaps because both Glass and Reich were New York cabbies in their scuffing-for buck’s days – quick off the mark when a foundation or arts council grant is in the offing.

This new breed of unconventional composers includes young British composer Steve Martland – an amateur bodybuilder, hard-core socialist, who conducts in Army fatigues and has recorded on the independent rock label Factory, out of Manchester.

Nigel Kennedy is the most visible of these classical outlaws. With an album which paired him with pop artist Steven Duffy and another of his versions of unreleased material by Jimi Hendrix, this ageing Aston Villa supporter still manages to outrage.

And sometimes come off as plain dumb and juvenile. In the early Neneties he announced it was time for him to experiment with hard drugs as had his heroes Hendrix (dead), Charlie Parker (dead) and John Coltrane (dead).

Such a headline grabbing profile wasn’t necessary for Polish composer Henryk Gorecki whose austere, minimal Symphony No. 3 rocketed to the top of the classical charts and even appeared in the pop top 10 in Britain in the early Nineties.

Such a headline grabbing profile wasn’t necessary for Polish composer Henryk Gorecki whose austere, minimal Symphony No. 3 rocketed to the top of the classical charts and even appeared in the pop top 10 in Britain in the early Nineties.

Gorecki’s work followed the similarly commercial success of John Tavener’s The Protecting Veil – a lyrical piece for Steven Isserlis’ cello and a small string section which was the biggest selling classical disc in Britain last year.

Struggling to explain the success of these spare but moving works, critics suggested they captured the mood of the troubling times.

And Tavener – whose earlier dissonant and challenging avant-garde works The Whale and Celtic Requiem on the Beatles’ Apple label in the late 60s have been reissued – perhaps has a mainline into the metaphysical by being a convert to Eastern Orthodox faith.

As critic Ian MacDonald wrote on the release of Tavener’s We Shall See Him As He Is: “Christianity’s talent for shooting itself in the foot is nowhere better displayed than its recent drive to demystify itself. After all, who goes into a church to get reasonable? Mystery is precisely what used to draw the crowds: no wonder gates are down.”

That note of wry cynicism may also be why the present crop of classical recordings are finding an audience. They reflect the times – albeit some of the more bleak aspects - in which we live and the needs of the moment.

When launching his own Point Music label with The Manson Family, one-time outsider Philip Glass said his recordings would be of “progressive works.”

“One of the things I’ve learned from years of touring is that there’s an audience out there that isn’t just interested in jazz or pop or dance or theatre or modern music, they’re interested in all kinds of music.

“I hear a lot of talk about ‘crossover artists,’ but what I’m seeing is crossover audiences.”

And in the post-modern age where the thirtysomething-and-beyond demographic has lived through the Beatles, hippies and punk, post-Vietnam disillusionment, gurus and gunmen, and when CNN and advertising assail the senses, the audience expects its classical music to reflect that.

Increasingly it is.

And, as Charlie Manson once said, cribbing a line from the Beatles, “It’s coming down fast.”

Like the sound of this? Then try this.

post a comment