Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Lila Downs admits she is surprised her music has become internationally successful. After all, much of what she sings is in Spanish, it speaks of the pride and plight of the Mexican and Indian communities, it can be politically flinty, and she has even managed to alienate folk purists by mixing in rock guitars, hip-hop, jazz and reggae influences.

As a cocktail of musical styles it just doesn’t seem to fit anywhere in the musical spectrum. Her early albums from the mid 90s often went unreviewed in mainstream media both in Mexico where she was born, and in the United States where she spends much of her time.

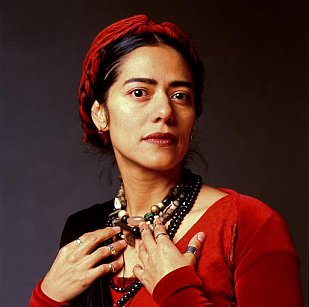

But in the past few years all that has changed: her striking appearance in brightly coloured traditional clothes and with her long dark hair in severe plaits has drawn comparisons with Frida Kahlo.

That association was enhanced by her appearing on the soundtrack to the 2002 Salma Hayak movie Frida movie. Her song Burn It Blue was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Song which she performed at the awards ceremony the following year.

Subsequently Billboard magazine said she had “one of the most spell-binding voices to grace the world music scene” and the LA Times weighed in with, “Lila Downs is a reflection of a 21st century world culture where ethnicity and national boundaries blur”.

In part that musical blurring comes from Downs’ own background.

Born in the politically volatile city of Oaxaca in southern Mexico, Lila (pronounced “Leela”) Downs is the daughter of Mixtec mother and an American professor of art and cinema from Minnesota.

She grew up in both Mexico and California before heading to the University of Minnesota where she graduated in anthropology.

But if this sounds like a privileged upbringing it needs to be noted she also sang in bars in Mexico City, and worked in her mother’s car parts shop where she would hear the men tell of the troubles faced by migrant Mexican workers in the United States, and of those who tried to cross the heavily patrolled border. It was those stories that prompted her to put them to music and take their struggles to a wider world.

The combination of music, stories, culture and politics was natural to her.

“I studied music from when I was quite young, but it was formal classical training and the repertoire for what a singer must learn was quite different from what we have chosen to blend together.

“The ‘school’ of bars and restaurants was my eye opener and it was then I met Paul [Cohen], my husband and collaborator. He was a circus clown then and lived on the streets as a performer. When we met we coincided on many different ways of life, and of looking at music.”

As an anthropologist Downs had studied weaving in a small Indian community close to where she had lived as a child. She was interested in how human culture documented its myths and culture.

“Colonisation has been a very big issue for me and many people, and I thought there had to be a way people made art and expressed these concerns. I don’t know if I’ve accomplished that in the music, but I’ve brought many people together who have these things on their mind.

“The weaving taught me about that in an abstract way, how women express their vision of politics and humour and birthing -- and this gift we have to be a woman.

“Many of the narratives in the weaving are quite ancient, but some are more recent, and some are very contemporary, they’ll have TVs and satellites.”

Noting that there are 62 distinct Indian languages in Mexico, she says she was also amazed that many Indian people in her region (“which doesn’t have a Wall-Mart or any of these modern forms of globalisation”) could speak fluently in their second language of English and so she began hearing stories.

Her 2001 album Border was dedicated to the Mexican migrants who have gone to the United States, and the spirits of those who had died trying to cross.

“I have been perplexed by the indifference to these issues. I heard these myths and contemporary stories and thought it would be wonderful if I could sing them into the world. Its something I grew up with, and of people having to cross the border. If you have any family members you have to deal with these issues of discrimination.”

But Downs and Cohen have done more than that and by bringing in other musical elements, and singing the occasional song in English, they have created their own genre, a kind of contemporary Mixtec crossover folk-rock.

Her recent albums slide effortlessly from accordion-driven Mexican barroom folk to slightly psychedelic rock, to aching ballads and traditional songs.

“Yes, there have been critics -- although they don’t tell it to my face. But there are so many different kinds of artists who come from Oaxaca who do a variety of our music in a more traditional way.

“But I don’t believe in purity because art is an open thing and you can’t stop it changing. The original music is still there for people who want to find it, but it did seem that music was dwindling into nothingness.

“So I’m happy to be part of that pride in our own traditions.”

post a comment