Graham Reid | | 8 min read

In the beginning it didn’t look like things would come together at all. The much anticipated press conference with conductor Maxim Shostakovich and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was in doubt.

Rostropovich was apparently studying his scores and Shostakovich had indicated he didn’t want to do it alone. Stalemate.

Both artists were in Wellington for the 1988 International Festival of the Arts and already Rostropovich had drawn out the superlatives from critics for his recital a few days before. His absence from the press conference would have questions about his performance and his being stripped of Soviet citizenship in 1974 left unanswered -- as well as dozens of other questions about his controversial interpretation of the cello repertoire.

At the appointed time, however, Maxim Shostakovich, son of the famous composer Dmitri Shostakovich, arrives in the small reception room of the James Cook Hotel.

At the appointed time, however, Maxim Shostakovich, son of the famous composer Dmitri Shostakovich, arrives in the small reception room of the James Cook Hotel.

He diplomatically answers anxious questions about whether he likes New Zealand and how he finds the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra (“they work very fast and learn quickly, that is a good quality”), but inevitably the questions are as much political as musical.

Shostakovich and his son sought political asylum in the west in 1981, not because of any one incident in particular, he says, “but for freedom for just normal things. When I left people had dark faces and sad eyes.”

“It’s not easy to explain what freedom is because for you people in a democracy it is normal. It’s like sunshine. If you wake up and it’s not there then you notice it.

“I remember somebody once said to me that if my father had worked in a free country maybe his music would have been different – polkas and very happy music,” Shostakovich says, snapping his fingers and bouncing in his seat.

“I said to him, ‘Franz Kafka lived in a free country so . . .who can say.’

He remembers clearly the political attacks against his father during the Stalin years of the late 1940s but says the music was like a mirror of the times.

“My father knew hunger, gulags, wars and revolution and when artists were forced to pay some kind of duty and write something pro-regime. But the Russian people have a good habit of reading between the lines,” he says with a broad smile.

During his final years in Russia certain work, particularly avant-garde material, was difficult to obtain.

“But for me that was not so important because I’m not a big lover of ultra avant-garde music. I like modern music but not ultra avant-garde,” he’s says with a shouting swoop of emphasis. “It’s impossible to describe in a newspaper,” he adds but indicates again with even more emphasis “ULTRAAA avant-garde.”

Of his father’s music he indicates no preference, saying he likes them all. But at present he likes the Fifth Symphony, the work he is to conduct the following night.

Growing up in the shadow of his father was not a problem to him.

“We have different professions. He was a composer and I am a conductor. I never compose and he only tried to conduct once and then said ‘never again.’ ”

The musical lineage is continuing in the family and he has recorded with his own son.

“We will play together again next month when my sister comes to America from Russia. But my son now prefers to compose music – pop music. I’ve told him to take a pseudonym.”

The brief meeting winds up and Shostakovich prepares to leave, thanking people for their questions as he goes.

But unexpectedly, Mstislav Rostropovich appears at the door.

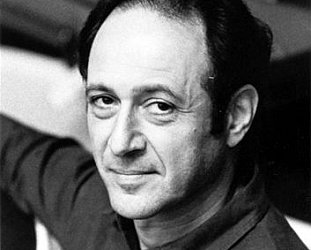

Like many celebrities only familiar from photographs he is smaller than expected, but immediately lives up to his reputation of making as many friends as he makes music. He works the room easily, shaking hands, and settles himself behind the table with a cup of tea and a chocolate biscuit.

He jokes about the lack of hot water in his room and tolerantly fields questions about whether he likes New Zealand and if he would like to spend a holiday here.

The only plan he reveals is that of taking leave from his position as musical director of the National Symphony in Washington.

“I would like to have more time to myself. I have had no vacation since 1974 and mostly I’d like to have my vacation in New Zealand. I’m so happy here – except with the room.”

He shows little interest in returning to Russia, pointing out that his situation is very complicated.

“I’m not an immigrant. I was in the West with official permission from the Soviet government, but in 1978 they - personally, Mr Brezhnev - stripped me of my citizenship. They took my passport and it’s forbidden for me to go back. But I’m not so poor I have to say, ‘Please, permit me to come back.’ ”

What Rostropovich says is undoubtedly true. Today he commands enormous concert fees and fills the largest halls wherever he performs. But he appreciates how the scale has changed for audiences and performers. He refers to his famous meeting with composer Benjamin Britten at the Aldeburgh Festival.

“A very large part of my soul is there,” he says expansively. “The first time I met Britten was in 1960 in London. Aldeburgh was such a beautiful small city but it has changed very much. My first concerts with Britten were in Jubilee Hall with a maximum capacity of 200 people.

“Many there were fisherman, the people Ben originally made the festival for. Now there are so many Rolls-Royces and it’s a much bigger hall.

“It’s not better or worse, just different.

“But some of the intimacy of the music is missing now and we need better acoustics.”

He recalls how 30 or 40 years ago he played to 800 to 1000 people and today audiences of three and four times that are not uncommon. The acoustic problem worries him a little.

“It’s significant that modern architects can make a condominium with many apartments and on the 10th floor you can hear anything said on the third. But if the same architect made a concert hall you could not hear anything from some seats. That’s a miracle.”

The matter of acoustics comes up again when he speaks of Shostakovich being a major influence on his life: “He is the reason I don’t compose anymore. I understood immediately that it was impossible for me to compose to one hundredth of his quality.

“As a cellist I heard so much great music – Bach and Beethoven – so I perfectly understood how bad my music was.

“As a student I had an apartment in Composers House in Moscow and only composers lived there. It had very bad acoustics. I was on the eight floor and if somebody on the first floor composed something I had complete knowledge of that.

“No, that’s good acoustics,” he says as an afterthought.

“But the composers competed with each other and I played Bach and Beethoven. If 95 per cent of those composers knew other music they would have stopped composing, but many of them only knew their own music.”

Since abandoning all ideas of being a composer from an early age, he has concentrated on the cello repertoire and conducting, not always to unanimous acclaim. Some critics have expressed alarm at his interpretations. His conducting of Eugene Onegin and Tosca at the Bolshoi in the late 1960s and his many recordings of the Dvorak cello concerto have been uneven.

“I have changed my style. I’m much more direct now, not so romantic or extreme. I used to be extreme at the climax of some pieces, almost breaking my cello or playing pianissimo so nobody could hear what was happening.

“We must perform in the style of the present. Sometimes great performers remain active for too long and stay with the old style a little bit. That’s why my friend Picasso had a long artistic life; he changed his style with time.”

He is less convinced about the present composers like Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Stravinsky, and says many of them were not satisfied with the instruments.

“I rehearsed the second Shostakovich Concerto for Cello and the composer was there during the difficult cadenza for two French horns. He said to me “Sava, I’m so sorry. Maybe I’ll die before somebody makes the instruments to play this.’

“It is the same with Bach. His ideas were so . . . Genius . . . and so projected for two, three, four hundred years. Now we have bigger halls and it’s impossible for those great ideas to rely on such instruments in the big halls.”

At 60, Rostropovich gives no indication of slowing down his concert schedule or recording work. He speaks of having completed all seven Prokofiev symphonies, Shostakovich’s first Concerto and Boris Godunov, with the National Symphony Orchestra, which is being used as a film soundtrack.

He rehearses “more often now than before” but is more intensely focussed in his practicing.

“There are some people who practise three or four hours. But I think about hockey or something. If I practise for 15 minutes I know what I must make of that 15 minutes and I use each second for something. After my concerts I have like a photo in my brain and each passage I know and I remember my last concert and which part was not perfect.”

At the concert the following evening where Shostakovich is to conduct his father’s Symphony No 5, and Rostropovich in the Dvorak Cello Concerto, the atmosphere is alive with expectation and tension.

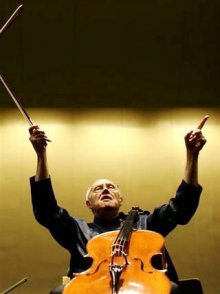

Inside the Michael Fowler Centre silence briefly overtakes the audience which suddenly bursts into applause as Shostakovich walks briskly to the podium, spins on his heel and, without hesitation, throws the orchestra into the opening bars.

It is an immensely powerful reading of the work driven on by a composer who works the climaxes and quieter passages with equal sensitivity.

His left hand shoots into the air to pull down as yet unheard percussion parts; and as he tosses his hand outwards Gary Brain’s percussion sounds out.

Huge scimitar-sweeps of his baton over the heads of the cellists and gentle gestures to soften and let flutes sound through come from him in a physically demanding display which brings sustained and genuine applause at the triumphant finish.

And in a gesture not lost on those who know the history of his father’s struggle with Soviet authorities, he holds the score up - and the applause is redoubled.

After the intermission he enters with Rostropovich for an equally powerful rendition of the popular Dvorak.

Rostropovich doesn’t disappoint, either in his interpretation or presence.

From the first notes he is intensity personified, his head nodding vigorously in the orchestral passages, bowed passionately over his cello as he plays the piece with a conviction few in the audience will have witnessed before.

At the end the audience is on its feet calling the pair back, not once but five times. The two jostle with each other playfully, each insisting the other take the podium in acknowledgement.

At the end the audience is on its feet calling the pair back, not once but five times. The two jostle with each other playfully, each insisting the other take the podium in acknowledgement.

Rostropovich plays a solo encore, the Sarabande from Bach’s Second Cello Suite, which finishes on a final mournful and icy note. The applause is slower to come as the audience is aware it can ask no more of the maestro – he has given a performance which, for many, would be seldom equalled in that venue and some would later say, with forgivable exaggeration, in their lifetime.

In the end, everything came together – the interview, music, the musicians and the moment.

Mstislav Rostropovich (1927-2007)

post a comment