Graham Reid | | 4 min read

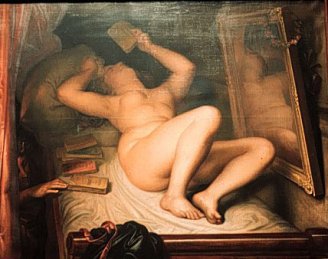

Antoine Wiertz was one pretty sick bastard all right. The gallery he demanded be built to house his gigantic paintings in his adopted hometown of Brussels is testament to an artist obsessed by death, disembowelment, rape, damnation and a virulent sexuality.

Everywhere flesh is impaled or torn, eyes glisten with horror, and spears drive through bodies. Over there is a beheading, on this wall a giant crushes people underfoot while biting on the leg of another unfortunate.

This delirious imagery is mesmerising, especially when rendered on such a scale. Some canvases stretch seven metres up the walls and drape four metres across.

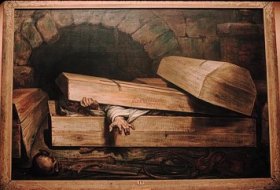

In one painting a child is being burned while its mother screams and mysterious figures hover in the shadows; in another a woman is shot while fleeing the carnage around her; in yet another a woman being raped turns and blows the head off her attacker with a heavy pistol.

And there are more horrors yet.

The Wiertz Museum in a small side street away from the historic centre of Brussels offers similarly conceived sculpture: two naked warriors engage in mutual penetration of each other with their swords and the trompe l’oeil in the corner of a half-clothed woman peaking through a door is behind the statue of a woman with a tambourine -- and a long sword impaling her forehead.

Whatever Wiertz was on -- and it seems to have been an inflated ego combined with religion -- this extraordinary 19th century visionary entertained some very strange thoughts.

Everywhere the work is suffused in a gloomy, dark romanticism of the nightmares of life and war. One painting is entitled Une seconde après la mort.

So who was this oddball artist whose genius wasn’t recognised by his contemporaries or critics, but who through sheer force of personality insisted the fledgling Kingdom of Belgium build him a studio which would be his monument and museum?

Antoine-Joseph Wiertz was born into a poor family in the small town of Dinant on the Meuse River in February 1806 and rose to become one of the main figures in Belgium’s romantic movement. His modest talent was encouraged by various benefactors but his artistic epiphany came when he saw Ruben’s Descent From the Cross while visiting Antwerp. Immediately he wanted to also work in such a grand baroque manner. He later embraced Raphael and Michelangelo, and his works accordingly grew in scale and a grandiloquence.

He never had any doubt about his gifts and when he came second in the 1828 Prix de Rome competition he fumed, “I am the first, yet I am not; opinions on the matter are divided.” He announced the judges decisions had been capricious and that others said a great injustice had been done him.

He never had any doubt about his gifts and when he came second in the 1828 Prix de Rome competition he fumed, “I am the first, yet I am not; opinions on the matter are divided.” He announced the judges decisions had been capricious and that others said a great injustice had been done him.

When he later submitted another work in the same competition he won, and with the prize money went to Rome to study and paint.

His works were initially small and modest, then he chose a topic befitting an enormous canvas, a battle between the Greeks and the Trojans.

At four metres by seven, it was constructed on a huge scale. He wanted to display it at the Paris Salon in 1838 but it arrived too late. Wiertz was livid and thus began his lifelong mistrust of critics and the art establishment. When a number of his works were accepted for the salon the following year they were poorly displayed and met with pubic indifference and critical ridicule.

Wiertz raged, called critics “those penny-a-liners”, and turned his back on Paris.

“It is my plan,” he said, “my new plan of Brussels, the capital of Europe … so that next to you Paris is no more than a provincial town.”

That his museum was once in a narrow and winding suburban lane but now lies literally in the shadow of the European Union buildings may be his prophetic revenge. It is the building he demanded be built to house his increasingly passionate and bloody visions.

In it there is a self-portrait from 1860. His full head of hair is brushed back from his broad, high forehead and falls thick behind his ears and along the collar. He has a dense, dark and neatly groomed beard and he is looking resolutely to his right, his dark eyes looking slightly upward as if to some event happening beyond the frame. His long sharp nose and distant icy stare suggest that, if anyone, this is a man who could persuade the state to build him a huge gallery on the promise he would donate to it his paintings. On condition they remain in the studio after his death.

The museum, unprepossessing from the outside, has been surrounded by the monoliths and museums of our own age: the Eurocrats of Brussels hurry past through their pristine and soulless corridors, and there is a natural history museum nearby which attracts a few tourists and gaggles of local schoolchildren.

To know of Wiertz is rare, but to seek him out is oddly rewarding. Inside the walls of his museum-cum-gallery are canvases which speak of another time, and certainly another frame of consciousness.

Technically Wiertz has his shortcomings. His foreshortening can be poor and some of his figures are disproportionate. If his seated Vulcan stood up he’d be about three metres tall and with a leg at right-angles to his hip.

Yet elsewhere he realised his visions with great delicacy. He references Raphael in a lovely Esmeralda and, in another thoroughly contemporary work, an unnaturally slender blonde engages the viewer as dispassionately as any Revlon model.

Wiertz died in his studio in 1865 and, as he wished and strange to the end, his remains were embalmed in accordance with ancient Egyptian burial rites.

And yet he did not die. His disturbing visions live on in this museum of his own making. Mad Wiertz never doubted his genius, only that it might take a while for others to recognise it.

“It is impossible to condemn or absolve a man’s work before his demise,” he once wrote. “It takes a least two centuries to judge a painter.”

So just another sixtysomething years to go then, Antoine?

Meantime those who find their way to your monument to yourself in a side street in Brussels come away bewildered and entranced by your hellish, impelled and visionary work.

You crazy sick bastard.

This is a chapter from Postcards From Elsewhere, available from Elsewhere

post a comment