Graham Reid | | 10 min read

The Iranian-born photographer and film maker Shirin Neshat left her homeland in 1974 to work in the United States and now, after a terrifying interrogation on her last trip back six years ago, has reluctantly accepted the description, "artist in exile".

Her homeland - once dominated by the Shah and politically oriented toward the West - is now an Islamist state which went through the revolutionary overthrow of the old regime five years after she left.

Today women wear the burqa and Islamic fundamentalists hold sway. It is a land she loves but finds problematic now, more so for having lived in New York and engaged with a progressive, intellectual community of artists such as Philip Glass who composed the music for her moving, ritualistic meditation on death Passage.

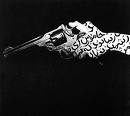

Neshat's early 90s photographic exhibition "Women of Allah" captured seductively hypnotic and internally contrasted images: veiled women, often very beautiful, with guns.

Her explorations of her relationship with Iran and Islam moved into videos in a series of extraordinary films which, without dialogue and through unforgettable image-making, attracted international attention. In her short film Last Word a woman takes a profoundly political and poetically soaring flight from a menacing interrogation room of men.

Now in her late 40s Neshat has moved on yet again, she is adapting Sharnush Parsipur's complex and metaphoric novel Women Without Men into a feature-length film. She has already finished one segment in which a swarm of men in black move across an arid landscape to a woman standing by the Tree of Knowledge. It is an astonishingly ppowerful image.

The phone call catches her at home, a puppy occasionally barking in the background.

What have you been up to today, are you very busy at the moment?

I am actually very busy, I am writing a script and trying to re-adapt a book into a feature-length film.

This is Women Without Men by Sharnush Parsipur?

Yes, I've actually shot a part of the film because this is a book which has a series of parallel stories. I've already shot one and am now revising the others. For the past few weeks I have been in the middle of the countryside by myself just working on the writing.

I would think it is a very difficult book to adapt, are you doing the screenplay by yourself?

Yes, and it is not only difficult to adapt but also to write because I am not really a writer. So it's an interesting experience and I'm learning a lot. I have some help, the writer of the book is around but also some other people. But I'm mainly the one doing it although I do bring in others when I need help and their advice.

You've made a natural progression from still photography into evocative video then film with narrative and now this, a feature-length movie.

Yes, when I reflect on myself and my work I seem like a very restless artist who doesn't stay very long with anything. But every time I arrive at a medium and begin to work with it after a while when I've made a certain amount of work I am anxious to move along to another thing. It doesn't mean I don't go back to them, but I don't feel particularly faithful to any of them. For example the photography of the Women of Allah which became a major aspect of my work. When I made video I completely turned my back to the photographs, particularly because everyone started categorising me. So after I made the video I quickly went to films where they became narrative and then when I made narrative work I was enticed to make a longer film. Although having said all that I am actually a cautious film maker. I have made nearly 10 films and nine were by myself. Still it does seem like a natural progression which has a little do with my own personality.

There is something very different regards audience about putting a feature-length film into the world than putting a series of photos in a gallery.

Yes, I am very aware of that and I think that is my biggest challenge. Every time you embrace a new medium you also embrace a new audience with different demands and I am going through that process now in the amount of the work remaining visual, the amount being abstract, and the amount of information and narrative you need to inform the audience. Then you have the whole history of cinema and art which you have to respect. Having said that I don't seem to be following a particular model in either cinema or art so as I go along I am trying to invent my own way and a perfect balance in art and cinema. That's why I have been working on this script for two and a half years and by the time I finish it will be another two years! [Laughs] It is not an easy task for someone like me to make this film, there are a lot of questions that come up.

You will still bring that photographers eye that you used 15 or 20 years ago however, the ratios of land to sky and so on. You are mindful of that idea of creating powerful single images on film within the context of a feature-length film?

Yes. When I made the first story of the book about one of the women and looked at the results I realised it was so much like my other work and that every image was photographically framed. It wasn't trivial or random, everything is carefully constructed and yet it had more of a sense of narrative which gave me the indication that the strength I have is image and not words. My story-telling system will always be different than conventional film, so I have to trust myself in the way I do it but also be conscious of the narrative and make sure that there is a progression even though it is not linear or done in a conventional sense. Having done the first story I can already tell you it is very close to what I normally do.

There seems to me from what I have seen - and they are Soliloquy, Tooba, Passage and Last Word - that there was leap from Passage to Last Word. That was a significantly different work in that it had a spoken narrative as much as a musical one. Do you look back and identify that was where you made a break with a particular part of your past.

I realised there were these tendencies running parallel in me, one was this inclination to make very political work and then the other tendency to make purely philosophical work. I am a person myself who is divided between these two tendencies because my life is defined by politics, but as a person I like things that are very poetic and philosophical. Therefore when I choose a theme it is for a particular reason.

For example when I made Passage the subject was death because it was something I was very concerned about through the loss of many people in my life at that time. And I wasn't meaning to make anything other than that although it does have other social and cultural flavours to it. But it is not directly political. But when I made Last Word it was because of a direct frustration with my government and the fact that I am not allowed to go back to Iran and had exactly that experience of interrogation.

Many artists, particularly the writer I am working with who has spent years in prison because of her books, experience this. So the whole question is of when a persons art and creativity becomes a crime and therefore redefines their relationship to their birthplace. And this man I had this experience with, I had to go back and face that again to get it out of my system. But it wasn't just about me but about any artist who have faced such a predicament where their country isolates them and punishes them for using their freedom of expression.

I see you described often as "an Iranian in exile". Is that how you see yourself, or are you just someone who lives outside the country? You have been away a very long time, you left in 74, but you have been back a number of times.

For a long time I resisted that definition because I didn't feel that way because I was going back and forth. Even when people were very afraid to go back I was going every year. But I had that terrible experience six years ago where I was blocked from leaving and had this nightmarish interrogation.

Later it became clear there were problems for me, but this is not unique to me. Eighty percent of people living abroad one way or another have a problem going back and I don't romanticise this. This is very real and I am among the people who most likely will have a difficult time when I get back. It might not be so, but there is a very good chance that will happen and I would end up in court.

There is a strong enough indication for me not to go back to therefore, unfortunately, although I really don't like to use that word [exile] I guess I am not able to go back merely from fear of trouble. This is the great grief for any person who does not have that choice, or is denied it.

In 2000 Time magazine asked you why people in the West were so fascinated by Islam. That's a question that would not be asked or answered in the same way in the current climate. Specifically for you as an artist have you noticed more interest in your work latterly because you are seen as a voice from within that culture?

Absolutely. In a lot of ways what we fear we also fantasise and for me the Islamic ideology as a religion and a force has been the replacement for Communism for a lot of Westerners, where we were both fascinated and terrified by that ideology. Islam has become the next biggest threat to the West because it has such a strong sense of ideology, and the notion of religion and faith having such importance in people's lives.

I think all of that complexity puzzles people in the West where people think the whole world is the same. Then suddenly you are faced with a culture which is not operating on the same level and believes in very different things. I am talking in very general terms but what I see is this notion of fear.

My work both reiterates the sense of violence and political reality of Islam yet the good aspects of Islam like the tradition and the beauty of the culture. [The West] packages the way people think about Islam whereas I don't leave it this way or that way but consistently insist on the two - good and bad - together.

The attention I have had is both positive and negative, and sometimes people's interest in my work is very superficial and they expect to read something very simplistic. Many times I think it does help because you can take the attention into something else.

Tooba is an example of that, it's a very complex film which superficially looks quite simple, but there is a lot more going on.

I'm glad you brought up Tooba because that, and Passage, I can see ... You see Last Word was just a little extra. [Laughs]. Tooba and Passage are beginning to branch off into a new direction and I am letting go of more direct iconography which is obviously Islamic, like the veil. In the new work I am doing, although it is obviously Iranian, I am letting go of a lot of those elements that seem to be a recognisable language in my work.

To some degree people are acquainted with that. But now all the obviousness is away and now they have to really think about what the work means. In some ways subconsciously this was my intention to make the work more universal and less possible to reduce it to one category. So when I worked with Mexicans to make Tooba and had Indian faces with no veil while the subject was very Islamic and Iranian it had a different flavour and I like that.

It is convenient to put artists in a category and in your case say, you were our "Iranian artist in exile". Now you aren't.

Exactly. [Laughs] They like to say I do the kind of work which puts men versus women and suddenly all of that is gone and I'm not doing that. The metaphors I use in my work are very universal, the notion of gardens and the Tree of Paradise. Now that I don't go back to Iran as much, obviously my work has changed.

You use black as a powerful metaphor, it can be loaded and menacing in Tooba, or the quality of mourning in Passage. Has that come about because of the black burqa in Iran? You seem drawn to black.

My attraction to black comes from being Iranian and when I was doing the black and white [photography] work I didn't feel my subject was very colourful. And ever since the revolution Iran seemed a black and white society. To me colour is only there for a purpose, I cannot use it at random. I'm interested, aesthetically speaking, in this relationship between people in black and what that represents in the context of a place of a colourful nature.

This is more than an aesthetic decision, for example in Passage the landscape is evolving from the sea and the desert and the canyons and all that but what remains constant is the people. So I needed this relationship between some things that change and some that don't, and how they interact together.

It's a little bit like a dance really and I thought about choreography in that respect. Tooba was pretty much the same thing where we drained the colour a little bit. I was fascinated by the idea of people coming from all different directions to the wall and the tree through the landscape and there was something very dramatic and powerful about this relationship, almost very haunting and frightening.

To me black is morbid and not a happy colour and I use it in that way always. The veil we wear is black, the women from Iran, myself included, we always wear black, we're very dark and melodramatic people. [Laughs] It's also just in my nature that I am very dark and I see that a lot of my figures are always wearing very dark clothes. I'm trying to change! [Laughs]

A Hawaiian shirt possibly?

That would be funny. [Laughs]

post a comment