Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Pain. The word rings like a refrain in any discussion of painter Frida Kahlo.

Her pain is writ large on the pages of even the most meagre of biographies: the crippling polio at age 6; the horrific bus accident at 18 and the more than 30 operations she endured as a result; the emotional wounds in her marriage to the great Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, 20 years her senior, whose serial infidelities hurtfully included an affair with her sister Christina . . .

Personal pain is often the foreground of Kahlo’s extensive body of work -- over half of it self-portraits -- but it also forms the backdrop: the birth pains of her country during the bloody Mexican Revolution (1910-20), a movement she so identified with she would insist she was born in 1920.

And there is the broad contextual pains of her dark symbology of death and abandoned Catholicism.

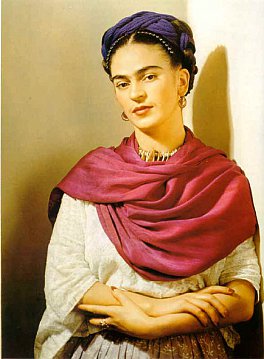

Inevitably then these anguishes -- collective or individual -- are rendered onto the canvases, metal, paper and masonite of this remarkable artist whose Mexican mono-brow stares out of her work and photographs with penetrating assurance.

The life and art of Frida Kahlo (1907-54) has become inseparable from pain. And passion for life.

Touring exhibitions of her art often come under collective headings such as Viva la Vida, a life-embracing title.

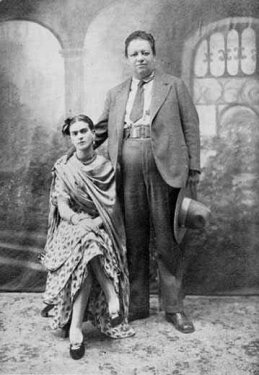

And among the works you can often find intimate and formal photographs of Kahlo and Rivera. Even in the most posed of these, like that taken on the day of their marriage, we can read something of the emotional intensity of their lives.

History has allowed for few women artists and, coupled with the rise of feminism, Kahlo has been elevated into the pantheon of great painters. Yet only the most misogynistic of critics, observers or the dictionary compilers who relegate her to “see: Rivera, Diego” would deny her a place.

With her unwavering stare enhanced by her natural inclination to a frown, the undepilated upper lip, renunciations of her femininity (she would crop her hair, adopt men’s suits then revert to her favoured traditional dresses and pre-Columbian jewellery) and the evidence of male and female lovers (Trotsky among them), it was inevitable that Kahlo would become a late 20th century feminist icon.

In 2000, New Zealand art writer Tessa Laird amusingly told how she came under the Kahlo spell at 13, acknowledged that “most artistic females have fallen prey to the Frida magic at some stage of their aesthetic development” citing Jacqueline Fahey, Judy Darragh and Jacqueline Fraser, and how she “cemented her enduring sisterhood with Frida”.

Laird also noted how Kahlo’s striking features have made her a t-shirt and tea-towel icon -- the artist as St Veronica, or Diana-like merchandise? -- in Mexico City where the Kahlo birthplace has been turned into a museum.

Photographers as diverse as Imogen Cunningham and her lover Nickolas Muray captured her exceptional beauty. Two bio-movies appeared with a couple of years. She is also Madonna’s favourite painter, for what it is worth.

In the Fifties, Rivera observed Kahlo was “the first woman in the history of art to treat, with absolute and uncompromising honesty, one might even say with impassive cruelty, those general and specific themes which exclusively affect women.”

However the commercialisation and secular canonisation of Kahlo The Feminist can detract from seeing her as the singular artist she was.

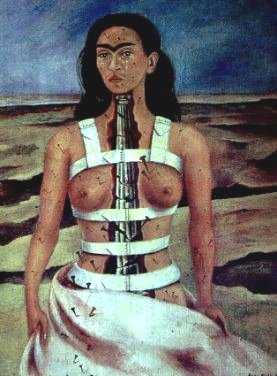

Beyond the obvious -- so much autobiographic analysis in oil, so much literal and metaphoric pain, so much proto-feminist iconography -- there is an artist who effected the marriage of contemporary European and traditional Mexican styles from folk art; developed an increasingly complex and personal symbolism; and rendered the political with little polemic but humanised by the personal.

Ironies abound in Kahlo’s life, not the least that the paralysing accident of September 1925, which imprisoned her on a hospital bed for nine months, forced this intellectually precocious child, disruptive student and enthusiastic Communist, to pick up the brush to get through the boredom and pain.

“Without giving it any particular thought,” she later told critic Antonio Rodriguez, “I started painting.”

Given her circumstances, and the placement of a mirror, it is hardly surprising she became her own subject.

“I paint myself because I am so often alone, and because I am the subject I know best,” she would say 20 years later.

And Rivera, whom she married in 1929, encouraged her to paint the events of her life.

Her portraits are compelling and increasingly became charged with a sophisticated personal symbolism rendered in the flat manner of the naïve and primitive styles of her country.

“From that time,” she said of the accident and her enforced isolation, “my obsession was to begin again, paint things just as I saw them with my own eyes and nothing more.”

Her work can possess a curious ambivalence: Kahlo is often the stillness at the centre of a swirl of highly charged emblems. She found her touchstone in the tradition of Western art portraiture (the subject surrounded by symbols of a trade or life, and an elongation occasionally redolent of Amadeo Modigliani whom Rivera had befriended while in Paris).

The chilling Two Fridas (1939) painted after her divorce from Rivera shows her in two different costumes, European and traditional Tehunan. But the figures’ two hearts are surgically exposed, the rejected Frida’s heart with a severed artery.

Me and My Parrots (1941) was painted during her affair with photographer Muray, the parrots adopted from Hindu imagery and evoking the eroticism of the love god Kama.

Kahlo, an independent spirit, didn’t shy from honest sexuality: Two Nudes in the Forest (1939) addresses her lesbian relationships.

When much contemporary art can be read as little more than therapy or a viable career option, Kahlo’s finest work -- and her strike rate is alarmingly high -- transcends that.

Her suffering may have been integral to her creativity. But the work has a dignity and depth that reach beyond the anxieties of her life.

Her marriage of personal symbology and fantasy elements make for body of work unique in the 20th century. It is replete with idiosyncratic totemism; elegiac reference; ambivalent sexuality; disturbing renderings of birth, marriage, miscarriage and murder; and her physical and psychological suffering.

Too often she has been dumped in with the surrealists whom she despised (“this bunch of coocoo lunatic sons of bitches”), yet it is hard to think of any other 20th century artist, beyond the increasingly fraudulent Salvador Dali, who so explored their own psyche to unearth such individual symbols and metaphors.

“Pain” may be the word which has become familiar and threadbare in any discussion of Frida Kahlo’s work.

“Unique” is perhaps the one we should be hearing more.

Bruce - Jan 18, 2012

I love diego kahlo fine art so much. Everything is so well done, and so imaginative.

Savepost a comment