Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Back in the early NIneties there was a modicum of good news about the career of the German rock band Endseig whose name meant Final Victory. It was that they weren’t particularly popular and their records sold fewer than a couple of thousand copies.

That however may come as small comfort to anyone who scans their lyrics.

“Throw them in prison of concentration camps . . . Kill their children, rape their women, terminate their race to fill them with horror . . . .”

And here’s Commander Pernod from Hamburg in a similar vein: “Filth must vanish, filth must go. Niggers must vanish, niggers must go . . .”

Or more pointedly Offensive from Cologne: “We are the army of outlaws, fighters and soldiers. We are back from the past and know no mercy . . .”

This was the brave new world of neo-Nazi skinhead bands whose lyrics and political agenda sidelined Ice-T and the LA gangsta rappers back to the playpen.

While most observers in Germany agreed that such bands had minimal influence, and applaud the fact no major international company signed one up, they were yet another symptom of the anti-foreign violence and the culture of Nazism that was on the rise in the new post-Wall Germany.

Late in 1992 the influential but previously little known German authors’ right society GEMA found itself in the headlines. In a move described as unprecedented it declared it would no longer handle material by composers who produced neo-Nazi songs and lyrics.

The organisation -- which was constitutionally required to accept all composers and said it welcomed a test case -- announced it would distance itself from those who produced works “which contradicted the constitutional principles of freedom and democracy”.

But while there were those who would ride with the angles against the often deliberately offensive neo-Nazi cult, others took a more detached position to question the nature of censorship in Germany today.

Suppression of the arts is not without precedent in Germany of course, and questions became more apposite with the release of two opera suppressed by the Nazis.

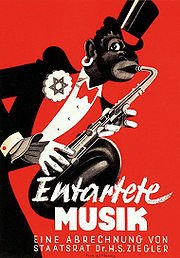

In a series of proposed releases at the time, Decca Records launched its Entartete Musik series and gave itself an ambitious brief: to release recordings by musicians in exile, music in evolution which was destroyed before it flowered and -- particularly relevant in the light of neo-Nazis on the rise -- important works lost, banned or destroyed by political disruptions “most conspicuously the music suppressed by the Third Reich”.

The first two Entartete Musik releases were Jonny spielt auf (Johnny Strikes Up) by Ernst Krenek -- a jazzy, sometimes atonal opera premiered in 1927 -- and Das Wunder der Heliane (The Miracle of Heliane) of the same year by the Jewish composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold.

Both were works purged from German cultural life and held up for ridicule and contempt at the notorious Entartete Musik (Degenerate Music) exhibition held at the Palace of Arts in Dusseldorf in 1938.

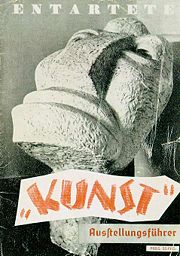

This was a Nazi propaganda show largely forgotten today and overshadowed by the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition of the previous year in Munich when paintings by Marc Chagall, Emile Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky and many others were similarly held up as perverse mutations.

In the hectoring rhetoric of the opening speech by Hans-Severus Ziegler, general director in Weimar, works in the Degenerate Music exhibition evoked “a veritable witches’ sabbath and the most frivolous spiritual and artistic cultural bolshevism, and [presented] the triumph of the sub-human, of arrogant Jewish impertinence and complete intellectual nullification”.

The exhibitions had two agendas: the purge the perverse, and “to produce a fully valid renewal of Germany as regards minds soul and character”.

Today such language has the familiar, chilling ring of totalitarianism about it, yet it was very much the argot of the time and leaned heavily on pseudoscientific theory in the service of cultural critique.

Even the word “degenerate” was borrowed from a term coined by criminologist doctor Cesare Lombroso to refer to an abnormal condition. “Abnormal” being understood as “deterioration”.

If the subtext of the language spoke of a larger and more insidious agenda, so too did the exhibitions betray a deeper purpose. They not only tapped a mistrust of intellectualism and artistic elitism, but served to undermine artists and musicians, and the institutes or credos they represented.

As Guardian Weekly writer Matthew Collins observed in a review of the recreated Entartete Kunst exhibition staged in 1992, “the idea was not so much to attack the supposed degeneracy of modern art, but to use modern art to prove that degeneracy existed, was an evil, and had to be destroyed. Which is why an elaborate, and in many ways hysterical, spectacle had to be made of it -- rather than simply destroying it.”

And the Entartete Kunst and Entartete Musik shows were certainly spectacles.

After its initial Munich showing in 1937, the art exhibition toured 13 cities in Germany and Austria and by 1941 had been seen by nearly four million people. The background to the music exhibition in 1938 -- photographs, caricatures, scores, unfavourable reviews and extensive quotes from Hitler -- can be traced to the period after World War I when the crisis of the bourgeois led to a loss of faith in the music of the grand German tradition.

As Albrecht Dumling observed in the liner notes to the Krenek opera: “Rather than idealistic symphonies and huge symphonic creations, [middle class audiences] now preferred smaller forms typical of chamber music. Opera shrank to works in single acts, in place of intoxicating harmonies there was plain linearity, and a matter-of-a-fact and often even grotesque style elbowed the earlier romanticism aside”

As high art lost its mandate and became disenfranchised, so influences from other sources infiltrated the music.

The Krenek opera Jonny spielt auf -- the new recording of which features Alessandra Marc -- has as its central character Jonny, a black violinist in a jazz band, in opposition to Max, described by the composer in 1948 as “ the awkward, inhibited, brooding Central European intellectual, and as such is the very opposite of the cheery, forthright chap from the world of the West [Jonny].”

In the context of its time Jonny spielt auf was a political and social grenade, and by its very internationalism it ran headlong into the political dimension of increasing German nationalism.

Hitler, an admirer of Pfitzner’s cantata Von deutscher Seele (From German Souls) visited Pfitzner in Munich, the city which saw itself in opposition to the more liberal Berlin. And, as Dumling notes, “Hitler saw himself not as a politician but as a cultural revolutionary”.

That revolution was exemplified by Hans-Severus Ziegler who was an active member of the Kampfbund fur deutsche Kultur (Fighting Union for German Culture).

Ziegler established the first nationalist-socialist weekly newspaper and became deputy head of the fledgling Nazi party in Thueringen. He was responsible for cultural policies and in 1930 became director at the Weimar Art College.

He immediately had pictures of Paul Klee, Oscar Kokoshka and Wassily Kandinsky removed, and decreed that concert programmes in Thueringen exclude jazz and music by Krenek, Paul Hindesmith and Igor Stravinsky whom he considered “musical Bolsheviks”.

“For years now, in nearly all areas of culture, “ he wrote, “the influence of alien races has been prevailing and threatening to undermine the moral strength of the German people.

“Prominent among these have been things like music for jazz bands and percussion, Negro dances, Negro songs and Negro plays, which glorify Negro doings and are a slap in the face for German cultural sensibilities.

“To do all that is possible to forestall these signs of decay lies in the interests of preserving and strengthening the German nation.”

Within three years -- with Hitler nominated as chancellor of the German Reich -- Ziegler’s edict became institutionalised and part of state policy.

The Entartete Kunst and Entartete Musik programmes were the visible manifestations of a broader state policy which would send trains rattling through silent countryside towards the charnel-houses of Europe.

“Just as degenerate art could be weeded out and destroyed” observed Guardian Weekly critic Collins, “so could degenerate elements of society be combed out of the body of German volk.”

With the release of the first two operas in the Entartete Musik series the more difficult nature of racism is again having to be addressed.

To recreate these exhibitions -- as was done in the early 90s, the Entartete Musik being opened 50 years after the first, and only 100 meters away from the original exhibition site -- could be seen as mere atonement, a chance to heroicise the works.

Whether these operas and others in the series are of merit can only be determined within the parameters of art.

It was Sir Kenneth Clark who observed that good religion does not necessarily make for good art. The same holds true for politics, good or bad.

But while it is to be applauded that these largely unheard works were retrieved from the pogroms of the past -- and stand as testament to the innate quality of endurance that art can possess -- they makes it no easier to deal with the present.

If Offensive, a neo-Nazi band from Cologne were indeed “back from the past and know no mercy” the question still remains: how are they to be dealt with?

post a comment